A Practitioner’s Guide to Rural Digital Inclusion

Rural communities must pair broadband expansion with affordable devices, hands-on training support, and AI literacy—to turn connectivity into jobs, entrepreneurship, and long-term local prosperity.

At a glance

Rural broadband gaps are closing. Now the work shifts from wires to people, providing digital skills training (including AI literacy), access to devices, and support, ensuring every rural resident can use the internet and digital tools to learn, work, start businesses, and improve their quality of life. This article serves as a practitioner’s guide to digital inclusion in rural America. For rural communities, a one-size-fits-all approach is ineffective for the diverse populations within rural America. This guide provides evidence-based, tailored interventions for specific groups, including low-income households, women, children and students, older adults, veterans, racial and ethnic minorities, individuals with language barriers, and individuals with disabilities in rural communities. Across these various demographics, five themes emerge as best practices:

- Embed digital support in trusted community institutions. The most successful interventions are rooted in places where people already have strong relationships.

- Pair resources with people. Programs achieve lasting impact when device distribution is paired with hands-on instruction and ongoing technical support.

- Align digital skills with real-world needs. Integrating digital and AI literacy into practical contexts for work or everyday life creates a lasting foundation for skill-building and confidence.

- Prioritize cultural and linguistic relevance. Design programs that align with local culture and identity.

- Recognize overlapping barriers and opportunities. The most effective programs meet people where they are, offering flexible, wraparound solutions that reflect the complex realities of rural life.

Digital inclusion is not only a social good but a critical economic development strategy. With 92% of jobs now requiring digital skills and workers with even one digital skill earning 23% more than those without1, investing in digital upskilling – including AI literacy – for workers and entrepreneurs is essential for new technologies to help close the rural-urban gap rather than continue to widen it.

92% of jobs now require digital skills and workers with even one digital skill earn 23% more than those without.

Closing The Digital Skills Divide - National Skills Coalition

From Broadband Access to Digital Inclusion

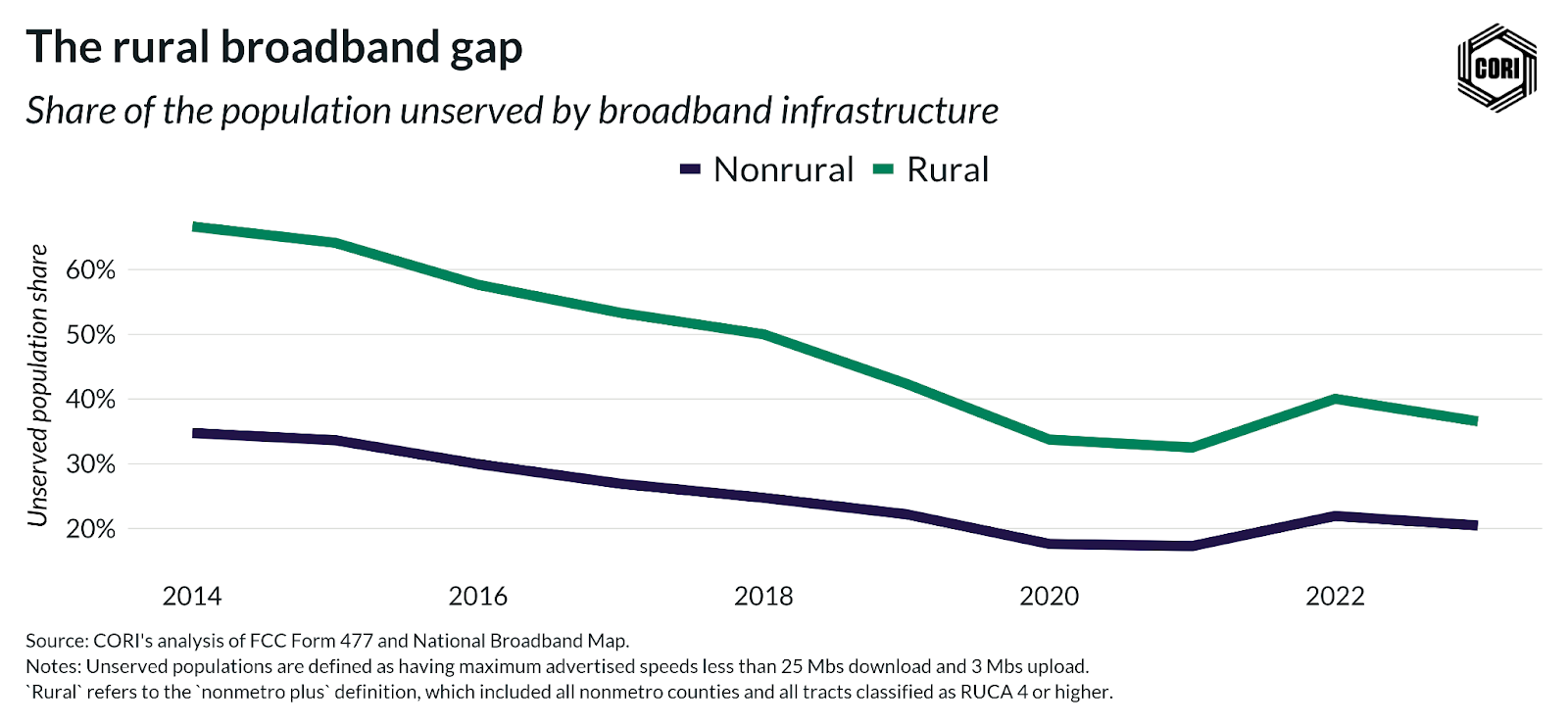

It’s a critical time to reflect on what it means to build a digitally equitable future for rural America. For years, the conversation has rightly centered on the fundamental challenge of infrastructure — the vital work of connecting the millions of rural residents left behind in the digital age. Thanks to the work of many small ISPs that drove broadband access by building fiber networks, and historic investments like the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program, the rural broadband gap is shrinking in states across the country.

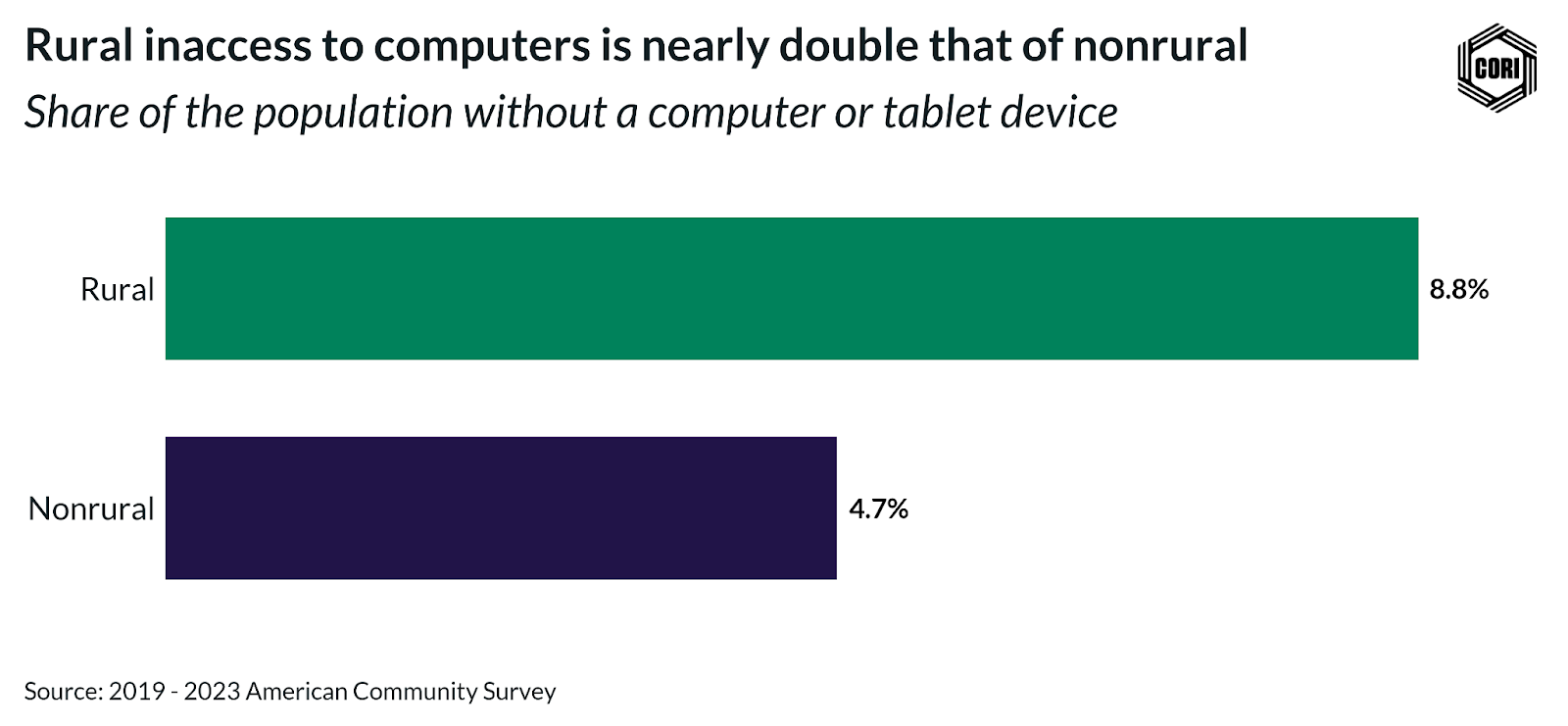

As practitioners on the ground know, connectivity is only the first step. True digital inclusion requires the availability of broadband, as well as equitable access to devices, training, and the ongoing support people need to leverage the internet to ensure all individuals can fully participate in today’s economy and society. Significant rural-nonrural gaps remain in digital skills and access to devices. For example, rural residents are nearly twice as likely as their nonrural peers to lack a computer or tablet, highlighting the depth of the device divide.

With the rise of AI, the importance of digital skills training and access has only increased. Rural stakeholders, including policymakers, educators, and workforce development practitioners, must make sure this new technology does not further widen the digital gap between rural and nonrural America, as previous technologies have. Digital skills programs should continue to offer the basic training they provided previously, but also expand to include AI literacy as part of a broader digital literacy initiative.

If rural youth are to become the AI experts of the future, early exposure to the technology is critical. As Shaniqua Corley-Moore, Head of Tech Talent Development at the Center on Rural Innovation (CORI), said, “Rural people need to see themselves as creators and not just consumers of technology.”

Raising awareness about what’s possible through digital skills programs — including the potential for tech and remote jobs, as well as the everyday benefits of digital access — should be a central pillar of rural digital inclusion strategies. Rural residents express a high level of interest in tech jobs and careers, but people who have more awareness of and exposure to tech work are more likely to act on this interest2. Rural residents are also largely dissatisfied with the accessibility of current training and education opportunities3. Online and nontraditional programs can help bridge this gap for rural learners4, but intentional outreach and promotion are needed to ensure people know these opportunities exist and can access them.

“Rural people need to see themselves as creators and not just consumers of technology.”

Shaniqua Corley-Moore, Head of Tech Talent Development at CORI

Achieving digital equity for rural communities requires moving beyond a one-size-fits-all approach. Rural America is a diverse tapestry of cultures and people. As research from CORI highlights, rural communities are home to a growing share of our nation’s Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous populations. The idea of a single, uniform rural America masks the incredible diversity of experience within and across rural communities5, 6.

Effective digital inclusion strategies must be tailored to the specific needs of the diverse populations that call rural America home. This guide draws on a wide body of research to provide practitioners with evidence-based interventions and promising models for supporting low-income households, women, children and students, older adults, veterans, racial and ethnic minorities, individuals with language barriers, and individuals with disabilities in rural America.

Tailored Interventions for Rural Populations

Effective digital inclusion work recognizes that barriers are not experienced uniformly. The most successful programs are those designed with a deep understanding of the specific challenges and motivations of the communities they serve.

Low-Income Households

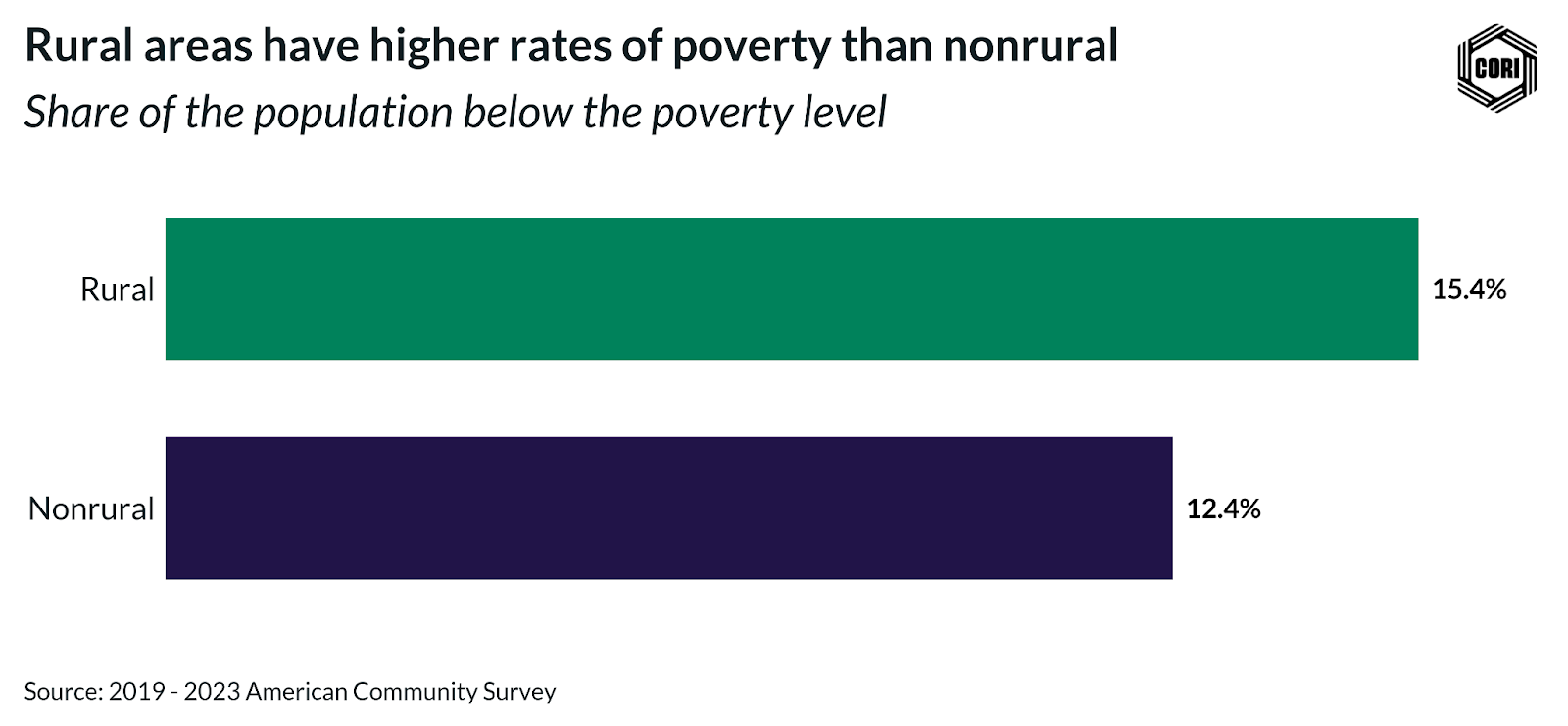

Affordability remains the most significant barrier to digital participation for individuals and families living on tight budgets. Income, along with age and education, is among the strongest predictors of broadband non-adoption7, 8, 9. This challenge is even more pronounced in rural areas, where poverty rates average 15.4%. The federal Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP) once helped bridge this gap — supporting nearly 26,000 households in a small state like Vermont alone — but its expiration in May 2024 left a substantial void10. The loss is particularly acute in persistent poverty counties, 80% of which are rural, where ACP participation was especially high and its sunset disproportionately harmed the most vulnerable rural communities11.

Strategies for Addressing Digital Inclusion for Low-Income Households

In this post-ACP environment, practitioners must focus on sustainable, long-term strategies.

Programs that bundle affordability assistance with hands-on training and technical support are far more effective for low-income households. These efforts not only connect residents but also strengthen rural economies. With 92% of jobs now requiring digital skills — and workers with even one digital skill earning 23% more than those without18 — investing in digital upskilling for low-income residents can expand local labor force participation, advance economic mobility, and fuel long-term rural growth.

Women

Women face unique barriers to digital participation that intersect with economic opportunity and entrepreneurship. Social norms, limited digital skills, unaffordable connectivity, lack of devices, and inadequate broadband access all contribute to women being left behind in the digital economy19, 20. For women in rural areas, these challenges are further compounded by geographic isolation and limited access to training resources and the wraparound support needed to participate fully. Yet women are increasingly turning to digital tools for entrepreneurship through e-commerce, remote work, and online services21, 22. Research shows that digital platforms can help rural women overcome barriers, strengthen technical skills, and build economic independence23, 24.

Strategies for Addressing Digital Inclusion for Women

Women in rural areas are not just beneficiaries of digital inclusion; they are catalysts for rural economic growth. Entrepreneurship rates tend to rise with rurality; entrepreneurship rates are higher for rural women than their nonrural counterparts27. By equipping rural women with broadband access and digital skills, communities can help them overcome geographic isolation, expand the reach of their enterprises, and drive inclusive, locally rooted economic development.

Children & Students

Rural students face significant barriers to completing homework due to limited access to broadband internet and appropriate digital devices. This “homework gap” has serious consequences: In 2018, 24% of teenagers from households earning under $30,000 per year reported being unable to complete assignments at least sometimes because they lack a computer or reliable internet access28. In 2019, only 76% of rural students had broadband at home, compared with 80% of students in cities and 87% in suburbs29. These disparities place rural students at a persistent disadvantage.

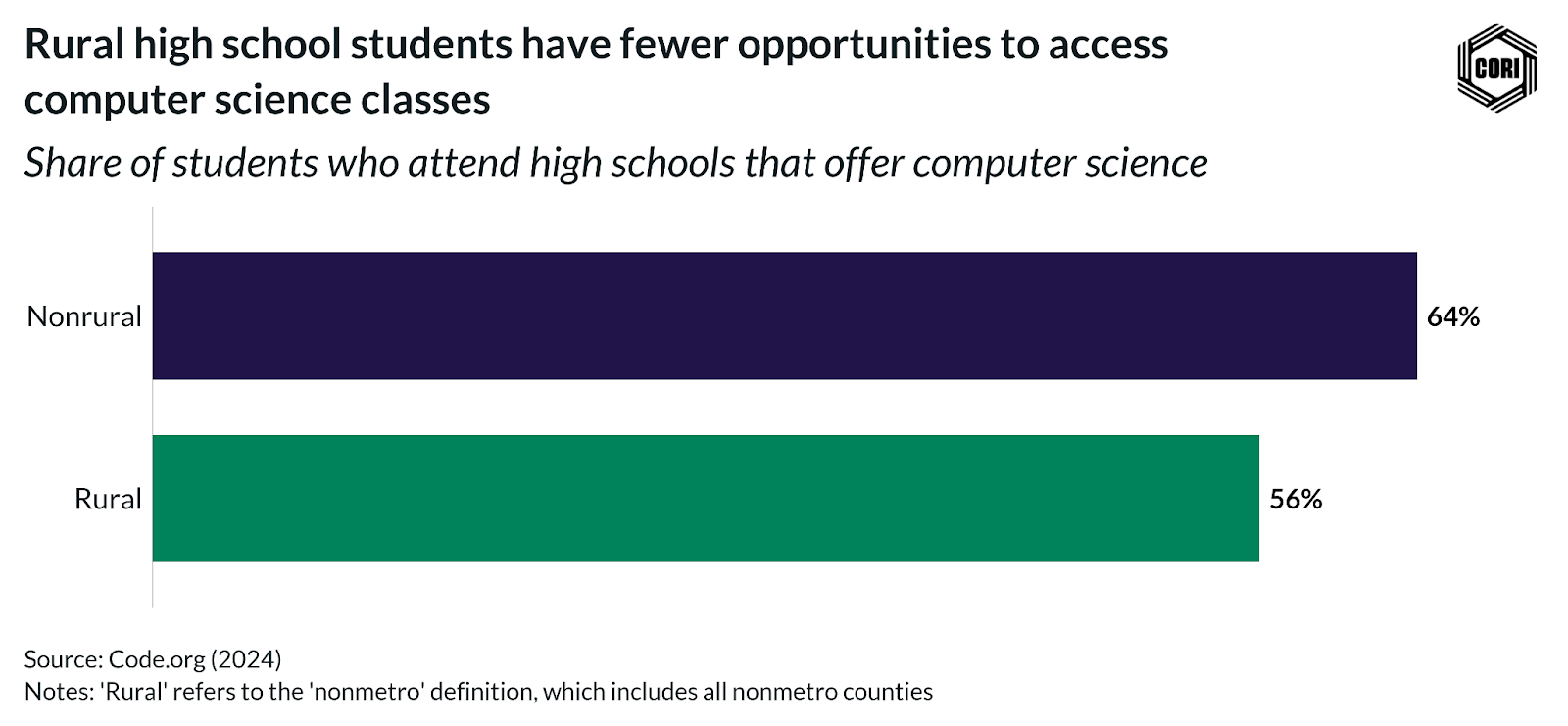

Access to computer science education is another area of inequity. Research shows that “offering just one computer science course in high school can increase students’ earnings by at least 8% by age 24” with the benefits “even more pronounced for low-income students, Black students, and young women”30. As artificial intelligence becomes increasingly integrated into workplaces and daily life, AI literacy has also become necessary31. Without reliable broadband and devices, rural students risk falling behind not only in computer science but in the foundational skills needed to thrive in an economy that is being shaped by AI.

Strategies for Addressing Digital Inclusion for Children & Students

Practitioners can help close these gaps through coordinated, community-based strategies:

Rural learners make up one-fifth of the nation’s K–12 students35, representing a vital opportunity for targeted investment in digital skills education. When rural youth have equitable access to broadband, devices, and STEM and computer science learning, they can become the next generation of innovators, choosing to remain in their hometowns as remote workers or tech-enabled entrepreneurs. When rural students gain digital skills and see the tech-driven careers that are possible close to home, communities can build a stronger foundation for inclusive growth and transform the story of rural “brain drain” into one of rural “brain gain.”

Older Adults (65+)

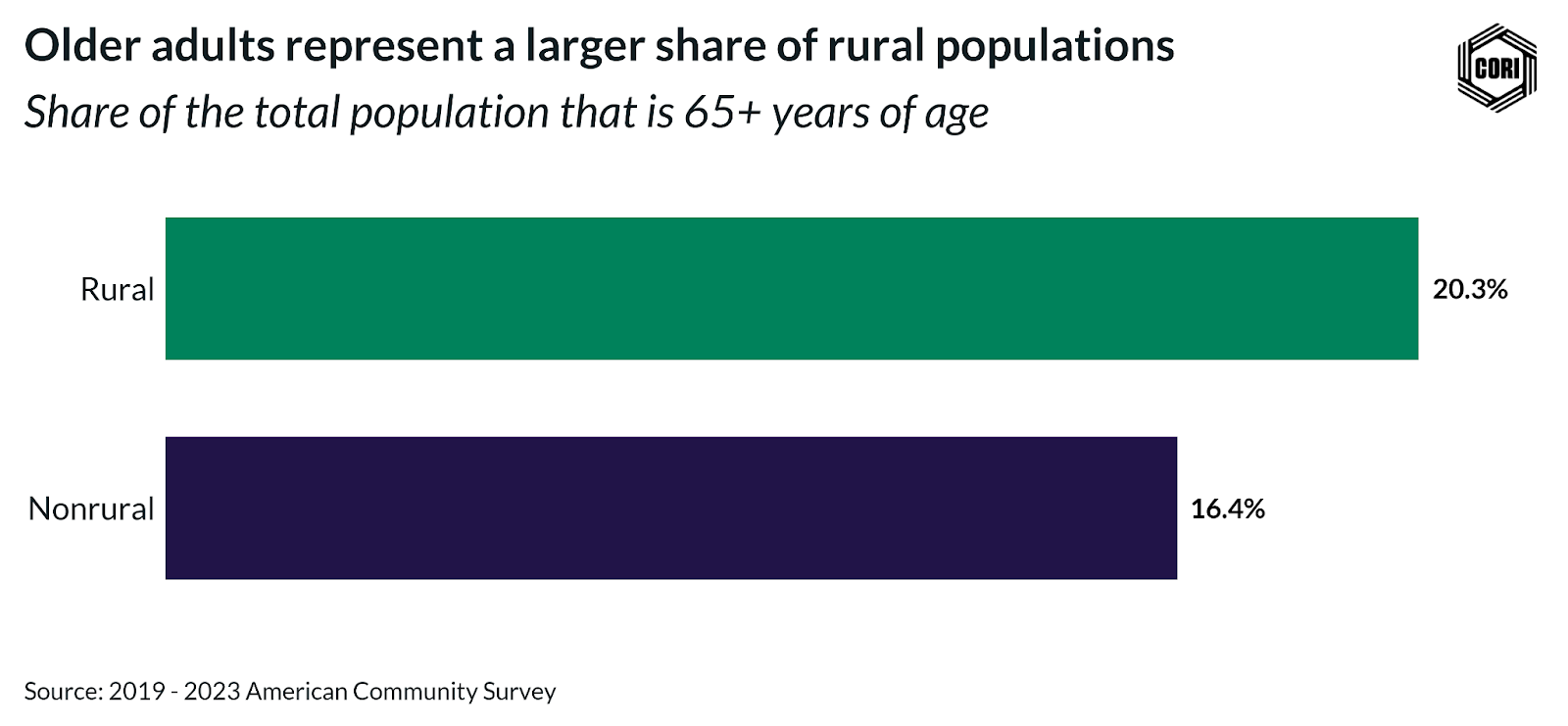

Rural populations are aging, with the number of older residents rising while younger populations decline. Over 20% of the U.S. rural population is over age 65, compared with less than 17% in metropolitan areas. Older adults often face unique barriers to digital inclusion, including gaps in digital skills, physical and cognitive impairments, discomfort with technology, and affordability challenges due to fixed incomes36 (Mullins, 2022).

Strategies for Addressing Digital Inclusion for Older Adults

A key to engagement is demonstrating the clear, practical value of technology for their daily lives37 (Lee & Coughlin, 2014).

Digital inclusion can significantly enhance the quality of life for older residents as well as unlock their potential as community assets. Older adults in rural areas bring decades of professional experience, deep industry knowledge, and refined problem-solving skills — resources that grow even more valuable when paired with digital proficiency. With access to digital tools and training, older adults can share their expertise as mentors, contribute as advisors or consultants through remote work, and stay actively engaged in local and regional economies. Investing in digital inclusion for older adults not only fosters personal well-being and social connection but also empowers them to become vital knowledge brokers who can strengthen local entrepreneurship and economic development efforts.

Veterans

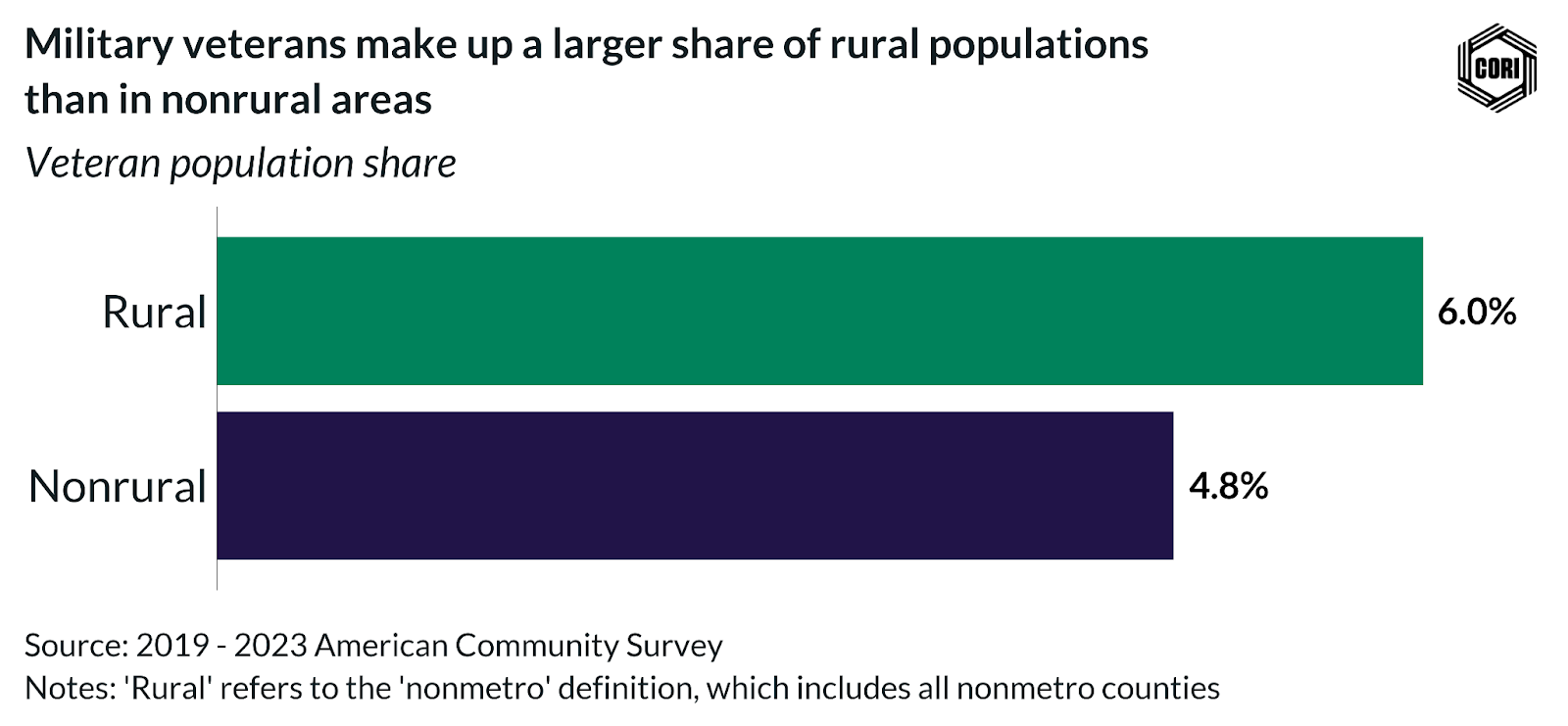

Rural veterans make up a substantial share of the U.S. veteran population. In rural areas, 6% of residents are veterans, compared with 4.8% in nonrural areas. Many rural veterans face compounded challenges related to geographic isolation, higher average age, and increased rates of disability44, 45 (Heyworth et al., 2024; Nearing et al., 2021). At the same time, younger veterans often leave military service with advanced technical training and strong leadership skills46 (Renna & Weinstein, 2019). For these veterans, the primary challenge is not acquiring new skills but translating existing ones into civilian career pathways.

Strategies for Addressing Digital Inclusion for Veterans

Digital inclusion initiatives serving veterans can advance this transition through several approaches:

Rural veterans, especially those who are younger, are a ready-made talent pipeline for technical and entrepreneurial roles. Veterans are twice as likely to be self-employed51 and three times more likely to own a franchise52 (Hale, 2024) than non-veterans. Digital inclusion efforts that align with workforce development and entrepreneurship can harness both the technical acumen and leadership experience of rural veterans, allowing veterans to put their skills to use in their hometowns, strengthening local economies while supporting their successful reintegration into civilian life.

Racial & Ethnic Minorities and Individuals with Language Barriers

Rural America is often portrayed as predominantly white, but the reality is far more diverse. Of the 48 million rural residents in the United States — about 15% of the total population — 10 million identify as people of color, representing over 20% of the rural population53. Yet, rural Native American, Black, and Hispanic communities continue to experience disproportionately lower broadband access compared with white residents54, 55. For rural residents with limited English proficiency, language and cultural mismatches, such as English-only content and complex interfaces, further limit digital participation.

Strategies for Addressing Digital Inclusion for Racial & Ethnic Minorities and Individuals with Language Barriers

Practitioners can address these disparities through the following strategies:

Rural communities of color and immigrant communities possess deep cultural knowledge, multilingual capacity, and strong social networks that can fuel innovation and economic vitality. Research shows that the rise in women and Black men working in high-skill occupations accounted for up to 40% of GDP growth between 1960 and 201058 (Hsieh et al., 2019). Immigrants are also roughly 80% more likely to start a business than native-born Americans, and their firms tend to employ more people59 (Azoulay et al., 2022).

Insights from the Rural Aperture Project highlight that rural places “thrive when they expand who gets to participate in opportunity.” In communities such as Starkville, Mississippi, and other examples featured in the report, locally grounded digital inclusion programs and partnerships with diverse community leaders are building bridges into the innovation economy. These efforts illustrate a broader truth: Expanding digital inclusion among racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse rural residents doesn’t just close equity gaps — it expands the talent base, creativity, and resilience that rural economies need to thrive.

Individuals with Disabilities

Rural residents are more than 14% more likely to experience disability than nonrural residents60. Americans with disabilities are three times more likely to report never going online than those without disabilities61. This is often compounded by websites and software that are not created with universal design guidelines in mind62.

Strategies for Addressing Digital Inclusion for Individuals with Disabilities

Practitioners can better serve individuals with disabilities by focusing on the following recommendations:

Individuals with disabilities represent an underutilized workforce asset with demonstrated advantages. Research has shown that employees with disabilities can be especially productive and reliable65 and that there is a compelling economic rationale for hiring individuals with disabilities, especially with regard to their attention to detail and motivation to work66. By building inclusive digital infrastructure and training programs, rural areas can retain talented and committed workers with disabilities who will have a positive impact on rural economies.

Principles for Practice: Weaving It All Together

As we look to the future of a fully connected rural America, our work must evolve. Achieving true digital equity means going beyond short-term fixes and toward building systems that empower every resident to thrive in a digital world. The infrastructure is coming online, but ensuring that everyone can benefit from it requires investments in people, skills, and trust.

Across all populations, several guiding principles emerge for practitioners working to advance rural digital inclusion:

Embed digital support in trusted community institutions.

The most successful interventions are rooted in places where people already have strong relationships — libraries, clinics, senior centers, schools, and the VA. Embedding digital navigators, trained community members who provide one-on-one help with internet access, devices, and digital skills, in these familiar environments builds trust, reduces stigma, and increases participation.

Pair resources with people.

Providing a device or hotspot alone is not enough. Programs achieve lasting impact when device distribution is paired with hands-on instruction and ongoing technical support. Without this guidance, devices often go unused and opportunities remain unrealized.

Align digital skills with real-world needs.

People are more motivated to learn when they see the tangible value of digital tools, whether it’s managing healthcare appointments, applying for a job, or running a small business. Integrating digital literacy into these practical contexts creates a lasting foundation for skill-building and confidence.

Prioritize cultural and linguistic relevance.

Effective outreach depends on materials and programming that reflect the communities being served. Deliver content in multiple languages, employ staff from within those communities, and design programs that align with local culture and identity.

Recognize overlapping barriers and opportunities.

Rural residents often experience multiple challenges simultaneously — economic hardship, limited mobility, lack of childcare, aging infrastructure, or language barriers. The most effective programs meet people where they are, offering flexible, wraparound solutions that reflect the complex realities of rural life. Inclusive design isn’t just about reaching more people; it’s about creating the conditions for everyone to participate in opportunity.

The Center on Rural Innovation’s Beyond Connectivity report underscores why this work matters: When broadband is not only available but actively leveraged, rural communities grow rather than shrink. Counties that pair broadband access with digital skills training and entrepreneurship support have higher business formation rates and higher income growth. Digital inclusion is not simply a social good; it is an economic strategy for rural resilience. Rural digital equity is achieved through the everyday work of local champions who expand access, build digital skills, and strengthen community connections across generations and institutions.

The Center on Rural Innovation’s Tech Workforce Development team works alongside rural community leaders to put these principles into action and bridge today’s digital divide. Through partnerships with local leaders, educators, higher education institutions, incubator hubs, coworking spaces, world-class tech-skilling organizations, and both local and remote employers, CORI helps communities build leadership capacity and develop strategies to grow inclusive tech economies. This collaborative approach connects educators with employers, aligns training with real job opportunities, and pilots programs that open pathways to high-quality tech careers. By integrating AI upskilling, CORI’s efforts transform digital equity into long-term opportunity, strengthening local ecosystems and proving that when rural communities have both broadband and the skills to use it, they can lead in the digital economy.

When everyone can participate in the digital economy, rural communities don’t just get connected, they thrive.

Source & Continued Reading

- Amanda Bergson-Shilcock et al. (2023, February, 06). Closing the Digital Skill Divide, National Skills Coalition

- New report finds a gap in high-paying tech jobs in rural America. (2022, May, 10). Center on Rural Innovation

- G.R.O.W. Generating Rural Opportunities in the Workforce Report. (2024). University of Pheonix

- Adam Dewbury PhD. (2025, March, 31). Online Program Managers and Rural Higher Education Institutions: Opportunities and Challenges. Center on Rural Innovation

- Who lives in rural America? How data shapes (and misshapes) conceptions of diversity in rural America. (2023, January, 12). Center on Rural Innovation

- Who lives in rural America? The geography of rural race and ethnicity. (2023, January, 12). Center on Rural Innovation

- Emily A. Vogels. (2021, June, 22). Digital divide persists even as Americans with lower incomes make gains in tech adoption. Pew Research Center

- Kathryn Zickuhr and Aaron Smith. (2012, April, 13). Digital differences. Pew Research Center

- Challenges to Achieving Digital Equity or “Why Covered Populations Are Covered”. (n.d.). Benton Institute for Broadband & Society

- ACP Enrollment and Claims Tracker. (2024). Universal Service Administration Company

- Continuation of the Affordable Connectivity Program can avoid cascading economic challenges for low-income families and underserved neighborhoods. (2024, October, 8). Center on Rural Innovation

- Summer Boucher-Robinson and Jake Varn. (2024, September, 20). States Reckon With Lapse of the Broadband Affordable Connectivity Program. Pew

- Jeff Baumgartner. (2024, December, 17). Broadband prices drop as speeds and competition climb – study. Light Reading

- Christopher Mitchell. (2010, May, 3). Breaking the Broadband Monopoly. Institute for Local Self-Reliance

- Christopher Mitchell. (2020, July). Broadband Internet Access: Fighting Monopoly Power. Institute for Local Self-Reliance

- Scott Wallsten. (2016, March). Learning from the FCC’s Lifeline Broadband Pilot Projects. Technology Policy Institute

- Stacey Wedlake et al. (2021, August, 13). Creating a Digital Bridge: Lessons and Policy Implications from a Technology Access and Distribution Program for Low-income Job Seekers. SSRN Social Science Research Network

- Amanda Bergson-Shilcock et al. (2023, February, 06). Closing the Digital Skill Divide, National Skills Coalition

- Norma E. Fernandez. (2024, April). From Fear to Confidence: The Digital Skills Journey of Underserved Women. Benton Institute for Broadband & Society

- Gustavo Streger. (2024, October, 30). What’s the Gender Digital Divide. Internet Society Foundation

- Henadi Al Saleh. (2020, January, 19). E-commerce is globalization’s shot at equality. World Economic Forum

- Leading the way: Female entrepreneurship is up 69% (2025, August, 6). The Currency

- Marni Baker Stein. (2023, June, 22). How online learning and remote work could level the playing field for women. World Economic Forum

- Sunil Kumar R PhD. (2025, January). Digital Empowerment: Transforming Rural Women’s Entrepreneurs. International Conference on Entreprenuership and Entrepreneurial Ecosystems in the Global Economy

- Evan D. Gumas et al. (2024, March 19). The Unequal Weight of Caregiving: Women Shoulder the Responsibility in 10 Countries. The Commonwealth Fund

- Empowering Women Entrepreneurs: SBA Adds Two New Courses to Online Digital Learning Platform, Ascent. (2022, November, 14). U.S. Small Business Administration

- Rural Women Entrepreneurs: Challenges and Opportunities. (2019, May, 8). National Women’s Business Council

- Brooke Auxier and Monica Anderson. (2020, March, 16). As schools close due to the coronavirus, some U.S. students face a digital ‘homework gap’. Pew Research Center

- Rural Students’ Access to the Internet. (2023, November). National Center for Education Statistics

- State of Computer Science Education. (2024). CODE Advocacy Coalition, CSTA, and ECEP

- Alyson Klein. (2024, December, 18). Without AI Literacy, Students Will Be ‘Unprepared for the Future,’ Educators Say. Education Week

- Katie McNeil. (2025, January, 29). The Benefits of School Bus Wi-Fi. Verizon Business

- Sarah Jenness. (2021. November, 29). Four Lessons From Developing Computer Science and Cybersecurity Pathways in Rural Communities. Jobs for the Future

- Kelly Mills et al. (2024, June). AI Literacy: A Framework to Understand, Evaluate, and Use Emerging Technology. Digital Promise

- Jeff Weld. (2024, April, 29). K-12 STEM Education For the Future Workforce: A Wish List for the Next Five Year Plan. Federation of American Scientists

- Emily Mullins. (2022). Building Digital Literact Among Older Adults: Best Practices. Samuel Center for Social Connectedness

- Chaiwoo Lee and Joseph F. Coughlin. (2014, June, 3). PERSPECTIVE: Older Adults’ Adoption of Technology: An Integrated Approach to Identifying Determinants and Barriers. Journal of Product Innovation Management

- Na Zhang and Qi Yang. (2024, April, 2). Public transport inclusion and active aging: A systematic review on elderly mobility. Journal of Traffic and Transportation Engineering

- Bindu Panikkar et al. (2023, January, 28). Transportation Justice in Vermont Communities of High Environmental Risk. Sustainability

- State of North Carolina Digital Equity Plan. (2023, December, 1). North Carolina Department of Information Technology

- Erin Emery-Tiburcio et al. (2022, December, 20). INCREASING TECHNOLOGY ACCESS TO FOR UNDERSERVED COMMUNITIES: CATCH-ON CONNECT. Innovation in Aging

- Skye N. Leedahl PhD, FGSA, FAGHE et al. (2023, June 1). Improving Technology Use, Digital Competence, and Access to Community Resources Among Older Participants in the University of Rhode Island Engaging Generations Cyber-Seniors digiAGE Pilot Study. Journal of Elder Policy

- Thomas Kamber. (2022). Helping Older Adults Get Comfortable with Technology Use. CSA Journal

- Dr. Leonie Heyworth et al. (2024, November). Veterans and Digital Equity: Planning for Success. Benton Institute for Broadband & Society

- Kathryn Nearing et al. (2021). Digital Divide Magnified for Older Veterans Living Off the Grid. Innovation in Aging

- Francesco Renna and Amanda Weinstein. (2018, October, 10). The Veteran Wage Differential. Applied Economics

- Charlie Wray et al. (2022, January, 28). Digital Health Skillsets and Digital Preparedness: Comparison of Veterans Health Administration Users and Other Veterans Nationally. JMIR formative research

- Alicia Cohen et al. (2023, January, 21). Evaluating the Effectiveness of Routine Screening for Digital Needs Among Rural Veterans. Annals of Family Medicine

- Kathryn A. Nearing et al. (2024, April, 4). Can telemedicine reach rural, older veterans on the edge of or caught in the digital divide? – Unique considerations for two distinct populations. Cogent Gerontology

- Veterans eligible to receive free cybersecurity training. (2016, August, 15). U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs

- Adrienne J Heinz et al. (2017, December 27). American Military Veteran Entrepreneurs: A Comprehensive Profile of Demographic, Service History, and Psychosocial Characteristics. Military psychology : the official journal of the Division of Military Psychology, American Psychological Association

- Chris Hale. (2024, December, 24). Why Veterans are nearly three times more likely to own a franchise compared to non-Veterans. U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs

- 15 Key Facts Shaping Rural America. Center on Rural Innovation

- Deborah N. Archer and Yuvraj Joshi. (2025, September, 1). Infrastructure Equality. Northwestern University Law Review

- The equity of economic opportunity in rural America. (2023, October 12). Center on Rural Innovation

- Vikki S. Katz and Carmen Gonzalez. (2015, August, 28). Community Variations in Low-Income Latino Families’ Technology Adoption and Integration. American Behavioral Scientist

- Kimberly MacKenzie. (2021, December 15). Public Libraries Help Patrons of Color to Bridge the Digital Divide, but Barriers Remain. Evidence Based Library and Information Practice

- Chang-Tai Hsieh et al. (2019, September, 30). The Allocation of Talent and U.S. Economic Growth. Econometrica Journal of the Economic Society

- Pierre Azoulay et al. (2022, March). Immigration and Entrepreneurship in the United States. American Economic Review: Insights

- Katrina Crankshaw. (2023, June, 26). The South Had Highest Disability Rate Among Regions in 2021. United States Census Bureau

- Andrew Perrin and Sara Atske. (2021, September 10). Americans with disabilities less likely than those without to own some digital devices. Pew Research Center

- Don Zimmerman et al. (2001, October). Making Web sites and technologies accessible. IEEE

- State of Vermont. Accessibility Policy.

- Erin Emery-Tiburcio et al. (2022, December, 20). Increasing Technology Access For Underserved Communities: Catch-On Connect. Innovation in Aging

- Brigida Hernandez et al. (2008, February, 21). Reflections from Employers on the Disabled Workforce: Focus Groups with Healthcare, Hospitality and Retail Administrators. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal

- Thomas Aichner. (2021, January, 22). The economic argument for hiring people with disabilities. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications