In the final installment of the Rural Aperture Project, a multi-story series funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Thrive Rural initiative, we build upon our previous exploration of the realities of rural America.

Our journey began with “Defining rural America,” where we examined how the way rural areas are defined and counted has a significant impact on our perception of and resource allocations to rural places.

We then delved into the question of who lives in rural America — the geography of rural race and ethnicity, and an exploration of how data shapes our understanding of these demographics.

We then delved into the question of who lives in rural America — the geography of rural race and ethnicity, and an exploration of how data shapes our understanding of these demographics.

Central to this effort is the goal of envisioning a future where rural communities and Native nations across the United States emerge as healthy places — environments where every individual not only lives with dignity but truly thrives. This vision compels us to consider health and well-being as fundamental threads woven through the narrative of rural America’s reality and potential. Data illuminates the rich diversity of rural America, underscoring the strength and variety within communities often mischaracterized as overwhelmingly white, conservative, and low-income.

In our third story, “The equity of economic opportunity in rural America,” we highlighted the widening economic divide between rural and nonrural areas, exacerbated by technological advancements and the rise of the knowledge economy.

Now we turn our focus to rural communities that are most affected by various systemic inequities but who are nonetheless demonstrating signs of vitality and improvement that suggest they are on the path to thriving. In addressing the limitations of solely relying on traditional short-term economic growth metrics, we emphasize a balanced approach that considers broader indicators of well-being that research suggests are leading indicators of long-run economic success.

Within our framework, “economic growth” is seen as a critical element of a wider strategy. In deeply disadvantaged areas economic growth is a necessary component of revitalization efforts not as an end goal but as a means to overcome structural inequities and expand community resources in areas where the economic base has been deeply eroded. Our focus on underlying community assets and barriers aims to foster long-term, inclusive growth that supports vibrant and equitable development.

This story weaves together insights from our previous stories to provide a clearer picture of rural America’s ongoing struggle for equity and opportunity, and spotlights the pockets of hope and advancement that signal a potentially promising and more inclusive future.

Four major takeaways from this story:

1. Understanding deep disadvantage is crucial

Recognizing the profound impact of persistent poverty and a broader understanding of deep disadvantage is essential. It’s not just a temporary economic setback but a legacy of generational decisions, deeply entrenched in the fabric of communities. Decisions that resulted in the concentration of poverty that shaped the geography of economic opportunity. Understanding these distinct racial and geographic patterns is necessary to address the root causes and break the cycle of poverty. It’s about acknowledging the past to effectively shape a more prosperous and equitable future for these communities.

2. Community-centered economic development is necessary

This approach outshines traditional economic development strategies by tailoring development efforts to local strengths and needs. It’s about understanding that sustainable growth in rural areas needs to start from the ground up. This means creating job opportunities across industries, diversifying the industrial base, and embracing the knowledge economy, making these areas more resilient to economic shifts.

3. Local entrepreneurship supports are key

Encouraging local entrepreneurship will support budding businesses in rural areas, and can ignite a chain reaction of growth and innovation, leading to a stronger and more dynamic local economy.

4. Communities should invest in the future with “race-to-the-top” initiatives

Investments in the community through education and career training, and infrastructure like broadband and innovation hubs are indispensable along with improving quality of life. They’re not just amenities, they’re necessities for rural areas to compete and succeed in the modern economy.

Acknowledgements

This project would not have been possible without the valuable insight, critique, and feedback from our collaborators who are embedded within a diverse array of communities, organizations, and institutions across the country, and helped to ground-truth our narrative framing and data, especially MDC for their wisdom and support.

Understanding deep disadvantage is crucial

Persistent poverty is not a momentary economic downturn but a generational challenge deeply rooted in geographical and societal contexts. A county is classified as being in persistent poverty when its poverty rate has exceeded 20% for at least three decades. This statistic is pivotal as it underscores a form of poverty deeply entrenched not in individuals, but in entire communities across generations.

Because this form of poverty impacts the broader community ecosystem, it impacts access to fundamental services and resources, and access to economic opportunity. Persistent poverty is a manifestation of deep-rooted institutional and structural issues, not merely the result of isolated events or individual choices.

There are distinct racial and geographic patterns to persistent poverty, with rural counties making up 80% of all persistent poverty counties. In Story 3 of the Rural Aperture Project, we showed rural Black and Native populations experienced persistent poverty at the highest rates.

Poverty measures only capture one part of the story, however, so to understand the implications of disadvantage we look instead to a more holistic measure, the University of Michigan’s Deep Disadvantage Index. This index incorporates social mobility and health measures along with poverty metrics. This research shows many similar geographic and demographic patterns to those found in persistent poverty research — both highlight the stark truth that the majority of this country’s most deeply disadvantaged populations live in rural areas. We know from Story 1 of the Rural Aperture Project that certain federal definitions of rural can sometimes obscure this fact.

In their new book, “The Injustice of Place,” authors Kathryn Edin, Luke Shaefer, and Timothy Nelson reveal that these deeply disadvantaged areas shared the experience of extractive economies, historically dependent on one industry, with a small group profiting while the majority remained impoverished. Research confirms that over-reliance on one industry, typically the tradable goods sector, has led to lower growth in rural areas (Goetz et al., 2018; Kilkenny and Partridge, 2009).

In Story 3 of the Rural Aperture Project, we discussed how many rural areas have historically suffered due to over-reliance on a single dominant firm or industry that was able to take advantage of the community’s geographic isolation (or remoteness), often resulting in exploitative labor practices and low wages. Many of the communities facing the deepest disadvantage are rural areas in the historic cotton belt where the effects of slavery, the most extreme form of exploitation, and Jim Crow are still evident today (Edin, Shaefer, and Nelson, 2023).

Rethinking economic development strategies for communities facing deep disadvantage

Communities facing deep disadvantage that are contending with job losses from the decline of a dominant industry or the closure of a large plant are more likely to rely on outdated traditional economic development policies that offer subsidies and tax incentives to attract large plants (see for example, Betz et al., 2012). Many policymakers and communities sincerely hope that traditional economic development incentive programs, a type of one-size-fits-all approach, may offer a quick fix to turn around a history of economic disadvantage.

But the fact that a widening opportunity gap between rural and nonrural areas has persisted for decades calls for a fundamental shift in our approach to rural economic development.

“Modern recruitment strategies have their roots in The Great Depression era Mississippi Balance Agriculture with Industry Act (BAWI), which initiated a wave of incentive-based economic development strategies that lower costs for businesses. Many communities still use these strategies to attract businesses to their area with lower tax rates, wage credits, real estate development, and other subsidies. Yet, very few businesses actually move each year and as a result a potentially costly strategy is geared toward a very small set of mobile firms.” (Conroy and Deller, 2018)

For most businesses, the incentive package does not change their location choice, making the incentive packages unnecessary as well as costly (Bartik, 2018). Even if a community can lure a business, there is little empirical evidence to suggest these traditional economic development incentives succeed in creating more jobs in the long run.

On average, incentivized firms fail to create more jobs than other non-incentivized businesses (Donegan et al., 2021). Those that receive financial assistance for capital investments are more likely to substitute capital for labor, for example by increasing automation that can replace local workers (Patrick, 2016). It is possible to find community success stories of business relocation, but research shows these are the exception, not the rule. “In contrast to the high profile accorded it by policymakers, business relocation plays a negligible role [in employment growth]” (Neumark et al., 2006).

As the size of traditional economic development incentive packages has increased — tripling between 1990 and 2015 — a growing body of research suggests that the costs are more likely to outweigh any benefits. For many small towns, the large upfront costs can be particularly burdensome and risky, especially if the company fails to create the jobs as promised (see for example, what happened in Mount Pleasant, Wisconsin).

Ultimately, “The more generous the tax incentives are, the higher tax rates have to be elsewhere to collect the same amount of revenue” (Ruger and Sorens, 2018). Traditional economic development incentive packages are paid for either through higher taxes elsewhere or spending cuts (Bartik, 2018). Spending cuts in K-12 education and other public goods and services can be especially detrimental to long-term economic growth and to helping individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds access economic opportunity.

Traditional economic development incentives that increase taxes on residents or on small businesses to pay for these incentive programs may also have the unintended consequence of crowding out more businesses than they create.

Indeed, a 2020 study found that traditional economic development incentives are more likely to crowd out economic activity, reducing the number of business startups, which along with expansions of existing firms (rather than firm relocation) are associated with higher job growth (Neumark et al., 2006). Small businesses and self-employment play a crucial role in promoting economic growth, especially in lagging regions (Stephens et al., 2013).

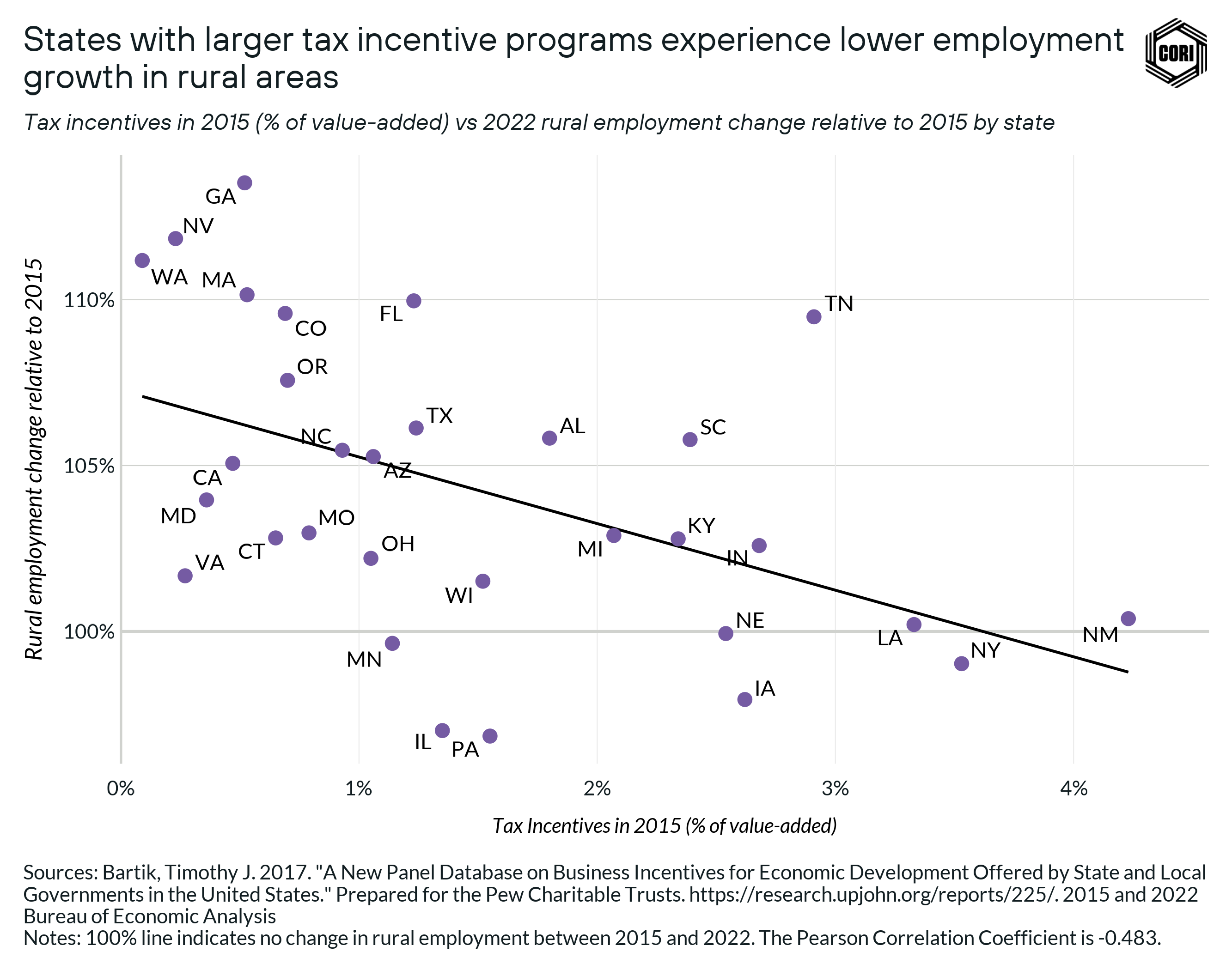

Thus, traditional economic development approaches are especially detrimental to the long-term growth prospects for rural areas. “The most robust estimates indicate that increasing the ability of governments to aid private enterprise has a significant negative medium-term effect on rural county employment levels” (Patrick, 2014). States with larger traditional economic development tax incentive programs (measured in 2015) tend to have lower employment growth in rural counties in the state.

There is little evidence that traditional economic development incentives are effective nor is there evidence that they are equitable.

The industries that receive incentive dollars are more likely to be large firms (with more than 1,000 employees), in large urban areas, and in industries that are predominantly white and predominantly male (Slattery and Zidar, 2020; Martinez, 2023). Additionally, traditional economic development incentive programs tend to be more costly for struggling communities as “poor places provide larger incentives and spend more per job” (Slattery and Zidar, 2020). Yet, traditional economic development programs are still the dominant strategy in many places across the nation. As previous research shows, places that are thriving are more likely to be doing so despite these strategies, not because of them.

Similarly, economies based on natural resource extraction, despite showing high initial growth rates characterized by a “boom,” are not sustainable because they tend to be more volatile with even larger “busts” that follow the boom (Black et al., 2005). Despite their initial wealth of natural resources, places in the U.S. that extract these resources tend to experience lower long-term growth characterized by the “natural resource curse” (James and Aadland, 2011; Douglas and Walker, 2017).

Although the natural resource curse is likely, it’s not inevitable. Sustainable economic development involves reinvesting natural resource gains back into the community (known as the Solow-Hartwick rule), requiring investment in various forms of community capital — (e.g., human capital like education or natural capital like amenities).

Research shows that many of the rural areas that are experiencing higher growth are doing so by capitalizing on their natural amenities, not by extracting their natural resources (Goetz et al., 2018). While extractive industries may initially lower poverty rates, the long-term effect on a community is to increase poverty rates (Deaton and Niman, 2012).

The natural resource curse is associated with negative long-term impacts on communities through various paths — for example, environmental degradation and disincentives to educational attainment (Douglas and Walker, 2017). These places typically require some type of policy or initiative to actively address the mechanisms behind the resource curse, such as focusing on education or increasing industry diversity to reduce volatility.

In Rural Aperture Project Story 2 and Story 3, we discussed how these histories provide a critical lens through which to understand the persistent poverty in these regions and exemplify a pattern observed across the most distressed rural communities. The reliance on a single industry, often tied to labor exploitation and inequities, has left deep-rooted economic vulnerabilities. Without alternative industries to replace them, or to buffer against these shocks, these places became stuck in cycles of generational poverty that made it harder and harder to develop without targeted interventions.

These patterns of persistent poverty indicate a need for tailored, place-based interventions. Place-based policies acknowledge the specific economic, social, and cultural contexts of a location, address its unique challenges, and leverage its distinct assets. The goal is to build opportunities from the ground up to help communities pivot into growing industries that offer a range of economic opportunities.

In the following section, we shift our attention to communities facing deep disadvantage that are outperforming expectations to show it is possible.

Thriving communities demonstrate steady progress

In places often relegated to the periphery of rural decline narratives, there’s evidence of improvement in expanding access to economic opportunity. This progress is incremental yet impactful and is reshaping the prospects of these communities.

Sometimes this progress just looks like maintenance, but in places that are burdened with decades of economic, institutional, and systemic marginalization this stability, or slow, steady growth can be a huge win. These are places that are swimming upstream against strong currents that might otherwise lead to decline.

We call these communities “thriving” because they are on the path to thriving, to prospering, to expected long-term growth that comes not all at once but with persistence, step by step.

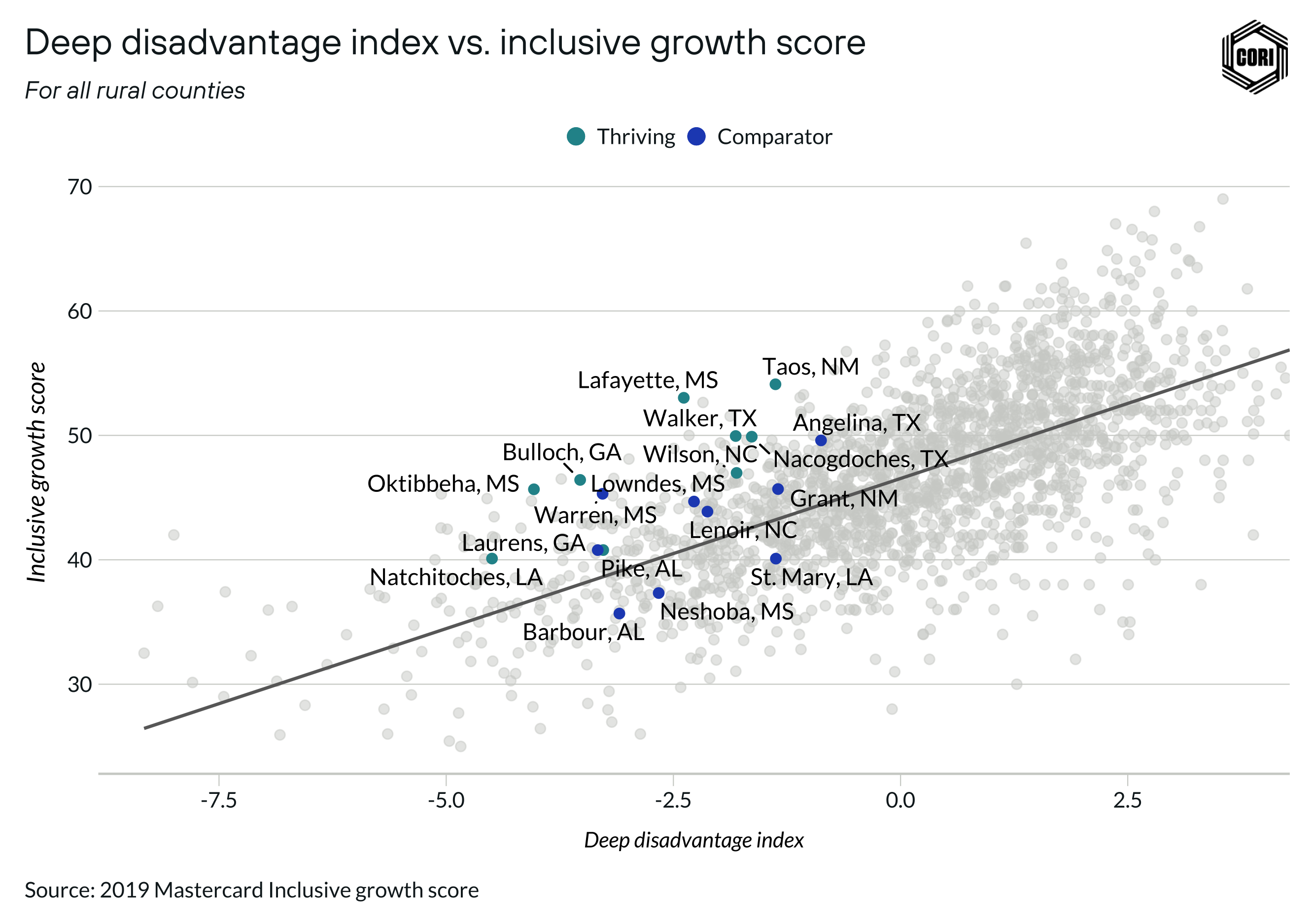

To highlight the progress that is possible in deeply disadvantaged places, we have identified communities with higher inclusive growth than we would expect given the social and economic challenges they have faced. Specifically, we examine the relationship between the index of deep disadvantage and Mastercard’s inclusive growth score, a measure of place-based economic development.

We can see that counties with a history of more advantages are associated with higher growth, while deeply disadvantaged counties are associated with lower growth. We selected counties that buck this trend, with a higher inclusive growth score than we would expect given their disadvantage index.

Communities on the path to thriving

Each of these communities illustrate a unique journey toward economic growth and community development, showcasing the ways in which small towns can leverage their unique strengths to overcome challenges and forge promising futures.

Crucial to our selection process was the input from our in-house Southeast region expert, and our external partners from MDC. Their expertise and insights added a valuable qualitative dimension to our quantitative analysis, ensuring a comprehensive and informed selection of communities for our study.

The deep disadvantage faced by the thriving communities we selected can be attributed to factors at the intersection of race, place, and class. All of the thriving places are rural micropolitan areas which Story 1 of the Rural Aperture Project showed exhibit the lowest growth when compared to other geographies (urban, suburban, and open lands). Most of the thriving counties continue to experience persistent poverty, though not all. Taos, for example, has recently fallen out of the persistent poverty classification.

All of the thriving communities have larger-than-average Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) populations that may be missed by our preconceptions about rural places that we highlighted in Story 2 of the Rural Aperture Project. Each of these communities showcases unique strengths and strategic choices that contribute to their economic success and demonstrate a trajectory toward inclusive growth.

To help explain how these communities may have been able to achieve this progress, we compare the set of thriving communities to other persistent poverty counties — other communities facing deep disadvantage — and a group of comparators. (We include only rural counties as defined by the nonmetro counties for these comparisons. Disadvantaged counties include all rural counties with a deep disadvantage index of -1.28 or lower.)

We selected comparable counties within the same state, having similar populations, demographics, and degree of disadvantage, although our thriving counties are slightly more disadvantaged than our comparator group based on the index of deep disadvantage.

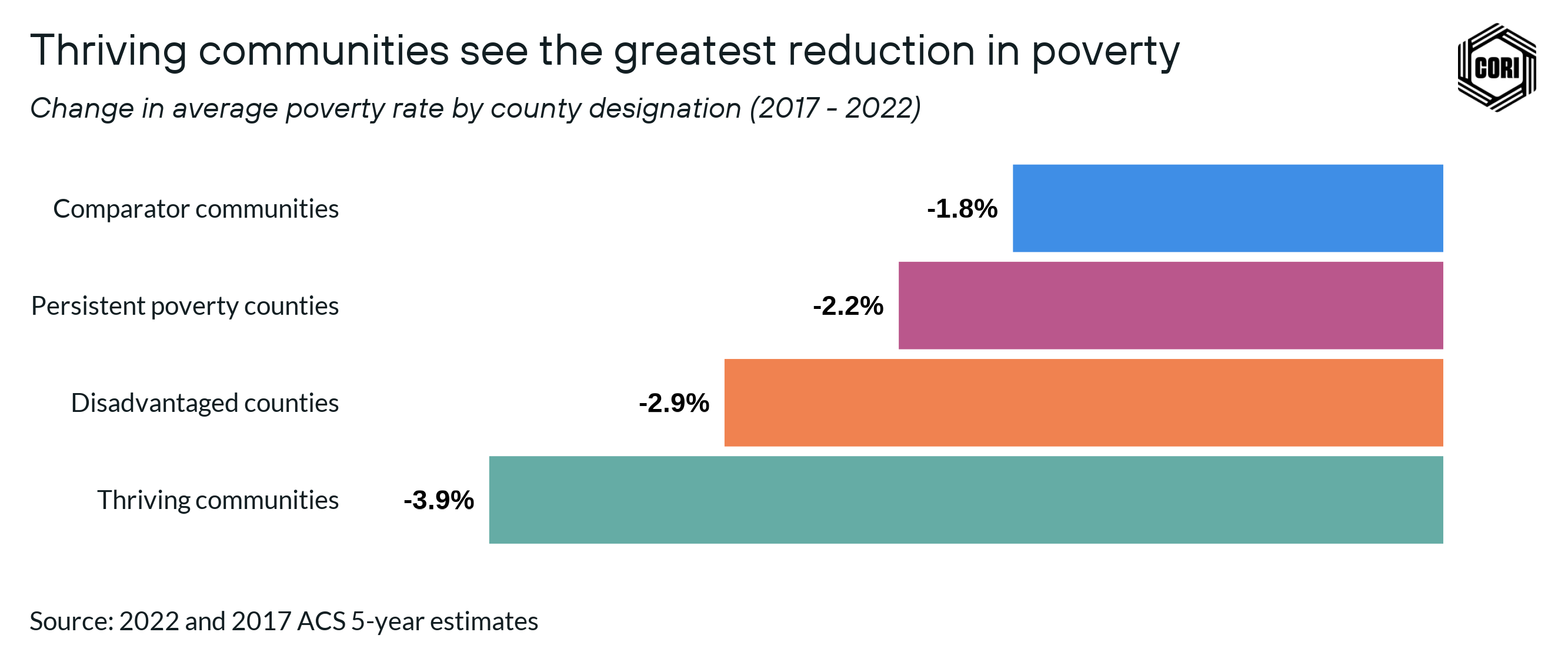

Despite their high poverty rates and deep disadvantage, these thriving communities have seen significant declines in poverty rates between 2017 and 2022, with poverty rates decreasing by 3.9% from a poverty rate in 2017 of about 24.5% to 20.6% in 2022. In thriving communities, the poverty rate declined even faster for Black residents, dropping 4.7% (compared with 2.9% for the comparator counties).

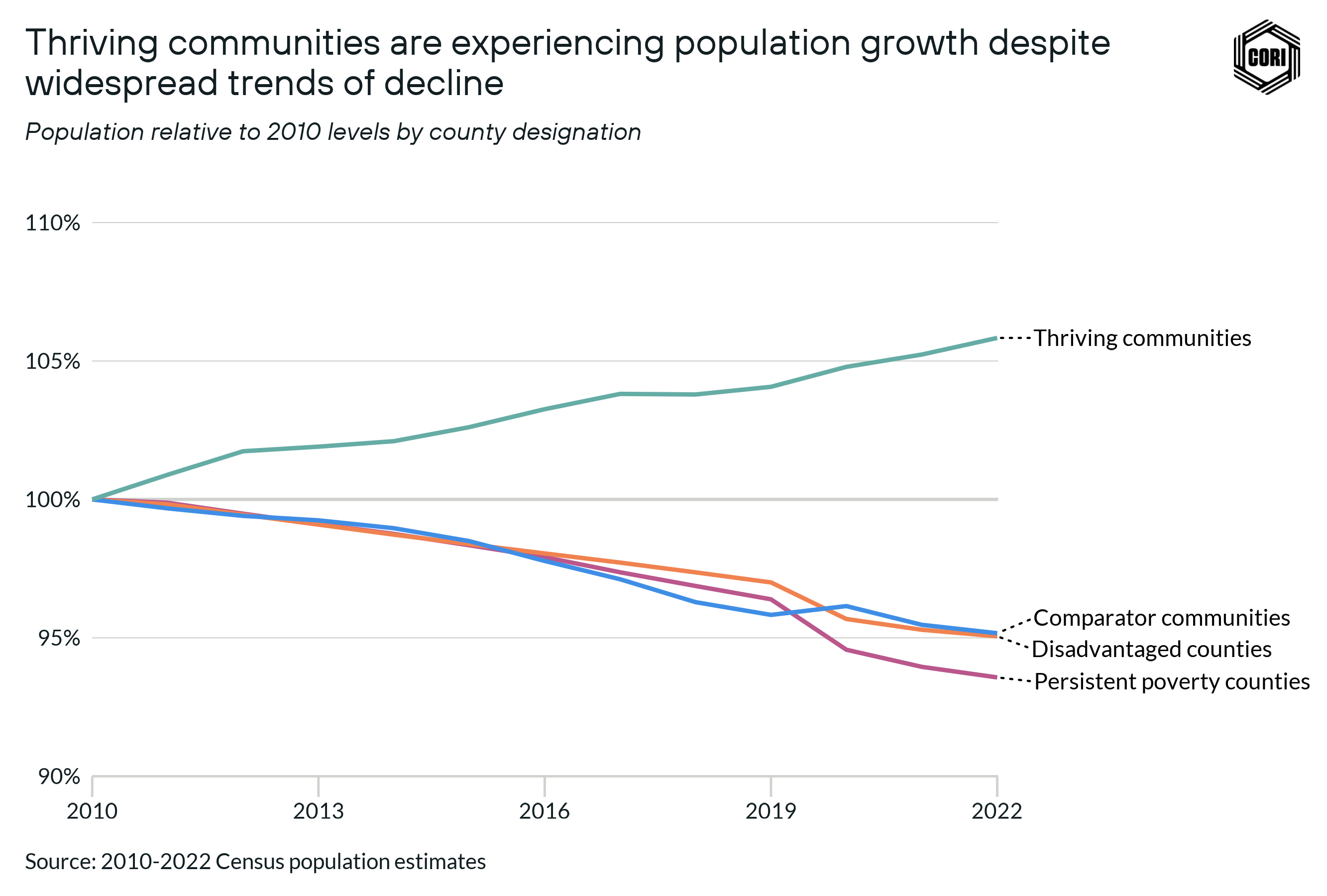

The thriving communities are on a path of steady growth — no small feat for places that have faced many obstacles on their path. The population growth rate for the U.S. hovered just under 7.7% between 2010 and 2022, while in communities facing deep disadvantage the population growth rate declined 4.9%.

Our thriving communities have managed to diverge from this trend, however, and are experiencing population growth closer to 5.8% (2010 and 2022 census).

When contrasted with similarly disadvantaged communities, these thriving communities showed similar patterns associated with their growth, namely:

- Growth from the ground up: increasing industry diversity and job growth with improved business supports and infrastructure such as broadband that promote entrepreneurship and existing businesses.

- Better access to healthcare and education: better healthcare outcomes and higher educational attainment from their public K-12 schools to their institutions of higher education, including nontraditional workforce training programs.

- Higher quality of life: promoting a more place-based approach to economic development that considers the foundational elements of the community, contributing to making it a nice place to live.

- Inclusive growth: economic growth is associated with lower poverty rates and reductions in inequality by improving access to opportunity within the community and across the region.

Economic development requires community-centered, place-based policies

When exploring rural resilience and development initiatives, considering place-based policies becomes vital. Economic theory has traditionally emphasized people-based policies and efficiency, often overlooking concerns about place-based strategies or inequity.

This disregard persisted despite mounting worries about growing income inequality and growing geographic inequality in the U.S. The expectation was that if economic opportunity declined in one place people would, or could, pick up and move to the place that offered greater opportunities.

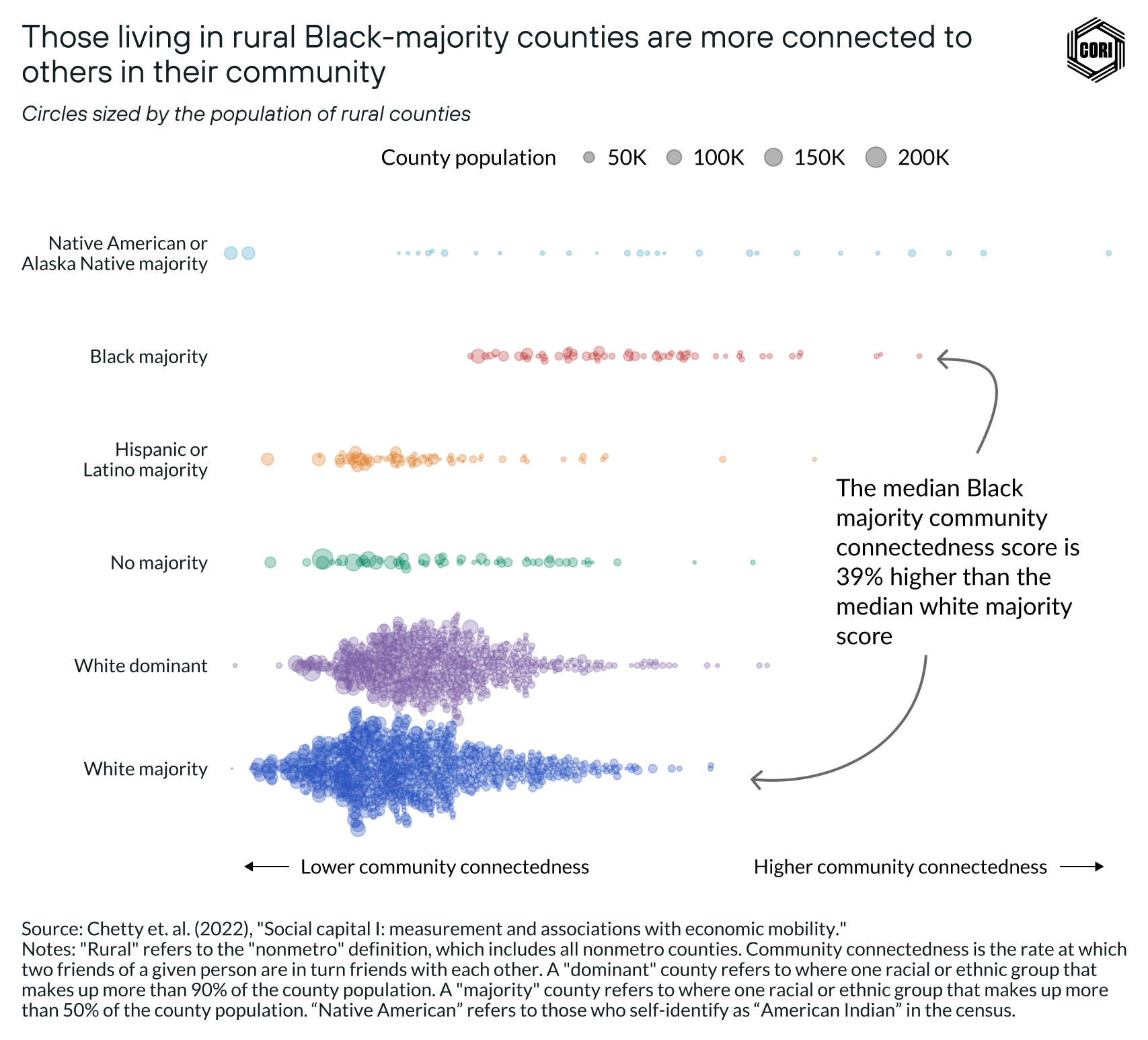

The assumption that people could easily relocate for better opportunities overlooks the complexities of uprooting lives. Moving incurs various costs — monetary and otherwise — such as severing social networks crucial for support. In rural areas, social capital is more important for growth (Taylor et al., 2023), and particularly important in rural Black-majority communities that are more deeply interconnected (see graphic from Story 2 of the Rural Aperture Project).

Despite the growing geographic inequality that would seem to amplify the potential rewards from relocating to a more prosperous community, research shows that fewer people are moving. Internal migration rates have been declining for decades. Falling migration rates are largely driven by the most educated individuals moving less — where geographic mobility has been replaced by mobility across industries (Stone, 2017; Partridge et al., 2012).

In the wake of the pandemic, there was a notable population shift toward smaller communities. Smaller counties experienced higher net migration and larger counties experienced lower net migration during the first year of the pandemic, however, these migration trends have since returned to pre-pandemic levels and overall migration rates remain historically low (Rogers et al., 2023, Frey, 2023).

While many workers returned to large urban areas, many families with kids have remained in smaller counties (O’Brien, 2023). The rise of remote work may have increased the potential for small towns to keep families, offering an avenue for mobility across industries previously unavailable in rural places while small towns also continue to provide better access to social networks that can support families.

These social networks, though not always quantifiable, contribute significantly to community well-being and may be an asset overlooked by some. Many rural communities are fostering social connectedness, beyond traditional institutions like libraries and schools, with innovation hubs. These spaces often emphasize personal connections, understanding that relationships play a pivotal role in thriving communities. Ashley Harris, community exchange coordinator at Gig East, an innovation hub in Wilson, North Carolina, explains:

“I really think it’s like that personal touch, right? And being able to call somebody by their name and know who their kids are and have conversations with people. I think sometimes when we think about aspects of business or running organizations or innovation, we miss the relationship part of things. And I think relationship is important because when people feel comfortable, they’ll let you know what’s good and what’s bad and they’ll let you know it in a way where you can improve it.”

Migration rates have historically been lower for individuals with lower socioeconomic status — and this remained true even during the pandemic. Thus, to access economic opportunity, especially in high-poverty places, people increasingly need to access it within their community.

To be effective at providing access to economic opportunities, policies should consider a place’s unique assets to help communities grow from the ground up. Instead of firm-specific tax incentives, policies should focus on expanding customized business services to locally owned, small and medium-sized businesses (Bartik, 2018), and foster an entrepreneurial culture of seeking out creative ways to leverage local resources to meet the needs and wants of the community (Kim and Kim, 2022).

Sustainable long-term economic growth from the ground up

“Efforts to promote entrepreneurial capacity may be among the few economic development strategies with positive payoffs in remote regions.” (Stephens and Partridge, 2011)

Business support services can make the difference in building entrepreneurial capacity. Innovation hubs are dynamic spaces that help bring together these support services, often functioning within a mixed-use coworking environment. They are more than just a physical location, they function as a nurturing ground where startups, entrepreneurs, investors, and sometimes academic entities can collaborate and intersect. They excel in building and enhancing networks, providing vital business services, and facilitating the exchange of ideas and resources, thereby driving progress and entrepreneurial success.

We are seeing these types of spaces emerge in our thriving communities:

- In Statesboro, Georgia (Bulloch County), Georgia Southern University has created an Innovation Incubator as well as the BIGx Accelerator program to enable cohorts of incubator participants to receive intensive entrepreneur support through peer advising and leadership development.

- Mississippi State University in Starkville, Mississippi (Oktibbeha County), also boasts a business incubator in their research park (completed in 2012).

- One rural tech startup, Hyperion Technology Group, that recently announced a $10 million defense contract award, got its start in the Renasant Center for IDEAs in Tupelo, Mississippi (Lee County). The Renasant Center for IDEAs has also helped other companies, such as Mabus Agency, a marketing firm for banks, to expand their business.

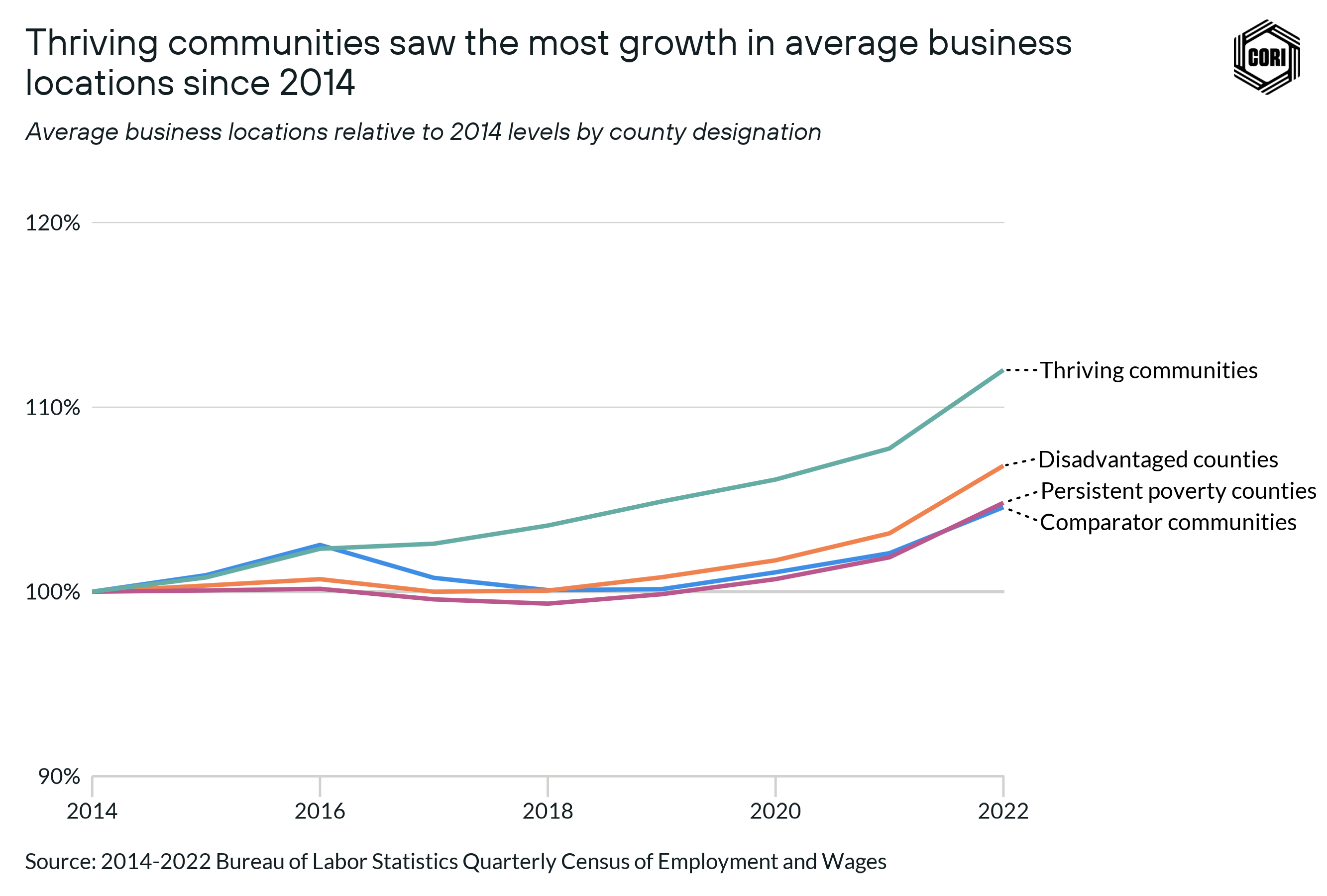

Thriving communities are seeing higher growth, on average, in the number of businesses established in the community, increasing by 12% since 2014.

New leaders are also emerging from thriving communities that are paving new paths to make entrepreneurship more accessible to all rural residents. For example, Juliana Bolivar, director at the Troy University Small Business Development Center Network (Pike County, Alabama) created a trailblazing entrepreneurship program tailored specifically for Alabama Department of Human Services clients. Bolivar’s collaborative and innovative approaches to small business development led to her being named one of America’s SBDC 40 Under 40 and an SBDC state star.

As Bolivar puts it:

“Entrepreneurship is more than just starting a business. It’s about transforming lives, building sustainable futures, and fostering economic wellness.”

Other thriving communities are on a similar path taking steps to expand their business support services further:

- Stephen F. Austin University in Nacogdoches, Texas, launched the Arnold Center for Entrepreneurship in 2022 which hosts an annual pitch contest, the Lumberjack Entrepreneurship Competition, and includes a small business resource hub.

- Northwestern State University in Natchitoches, Louisiana, recently received over $2 million in federal funds to build an innovation center.

- And the University of New Mexico-Taos was awarded a Build to Scale grant in 2022 to fund a new accelerator program in their HIVE innovation hub.

These spaces and programming are important hubs for entrepreneurs to build out a local innovation economy.

In Story 3 of the Rural Aperture Project, we discussed the importance of allocating more venture capital to support rural small businesses that received less than 1% of venture capital dollars in 2018. Natchitoches is bucking this trend, receiving the fourth-highest amount of venture capital funds among micropolitan areas between 2019-2021 (CORI analysis of SEC Form D and ACS data).

Small businesses, regardless of their location, also need access to markets. While innovation hubs can work to grow the networks of startups, investments in infrastructure can also help to connect startups to markets. Many rural areas lack access to larger markets, making infrastructure investments crucial for their success.

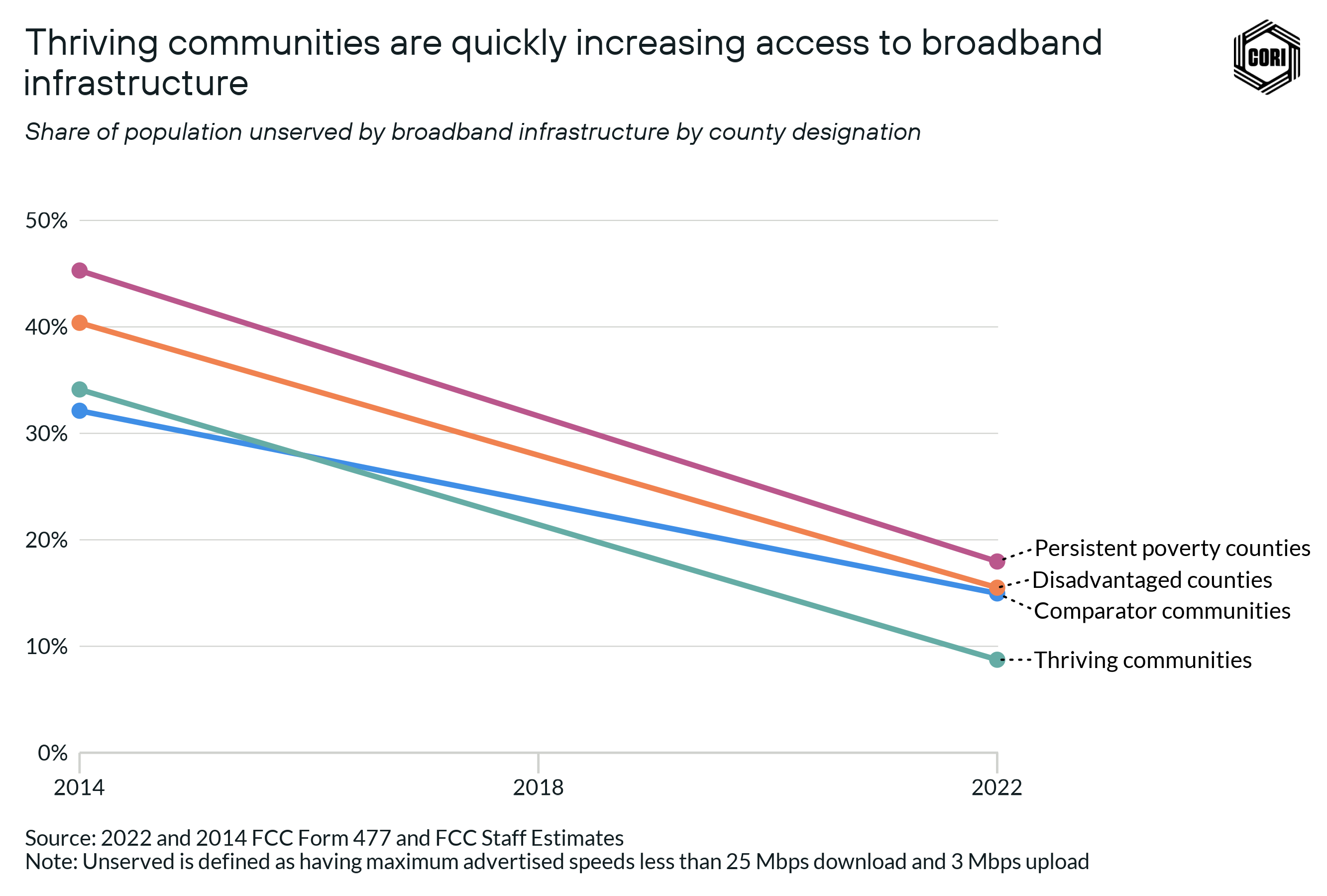

Whereas proximity to a larger metropolitan area provides access to markets for many rural businesses, broadband is necessary, especially for more remote rural businesses. To have the broadest impacts, broadband must also be affordable and accessible. The thriving communities now have the lowest share of the population that is unserved by broadband among the comparison groups despite having a higher share of the population unserved by broadband than the comparator group in 2014.

Broadband access is tied to a host of local economic benefits such as higher GDP and business formation, making it a vital economic resource (Story 3 of the Rural Aperture Project). “Researchers widely agree that high-speed Internet improves economic outcomes of rural areas, whether it is through increases in business activity or in more general economic development measures (e.g. productivity, jobs, income)” (Mack et al., 2023).

Infrastructure investments such as broadband are effective and efficient in creating the conditions necessary for long-term, sustainable economic growth. Infrastructure investments in depressed regions also have substantially lower costs per job created compared to traditional economic development incentives (Bartik, 2018).

Additionally, infrastructure investments don’t leave with a company but are investments built to last (Schwartz, 2018). Instead, infrastructure investments are part of a “race-to-the-top” approach that proves more effective for economic development (Goetz, et al., 2011) as it helps lay a strong foundation for businesses across various industries.

Industry diversity as a pathway to increase access to economic opportunity

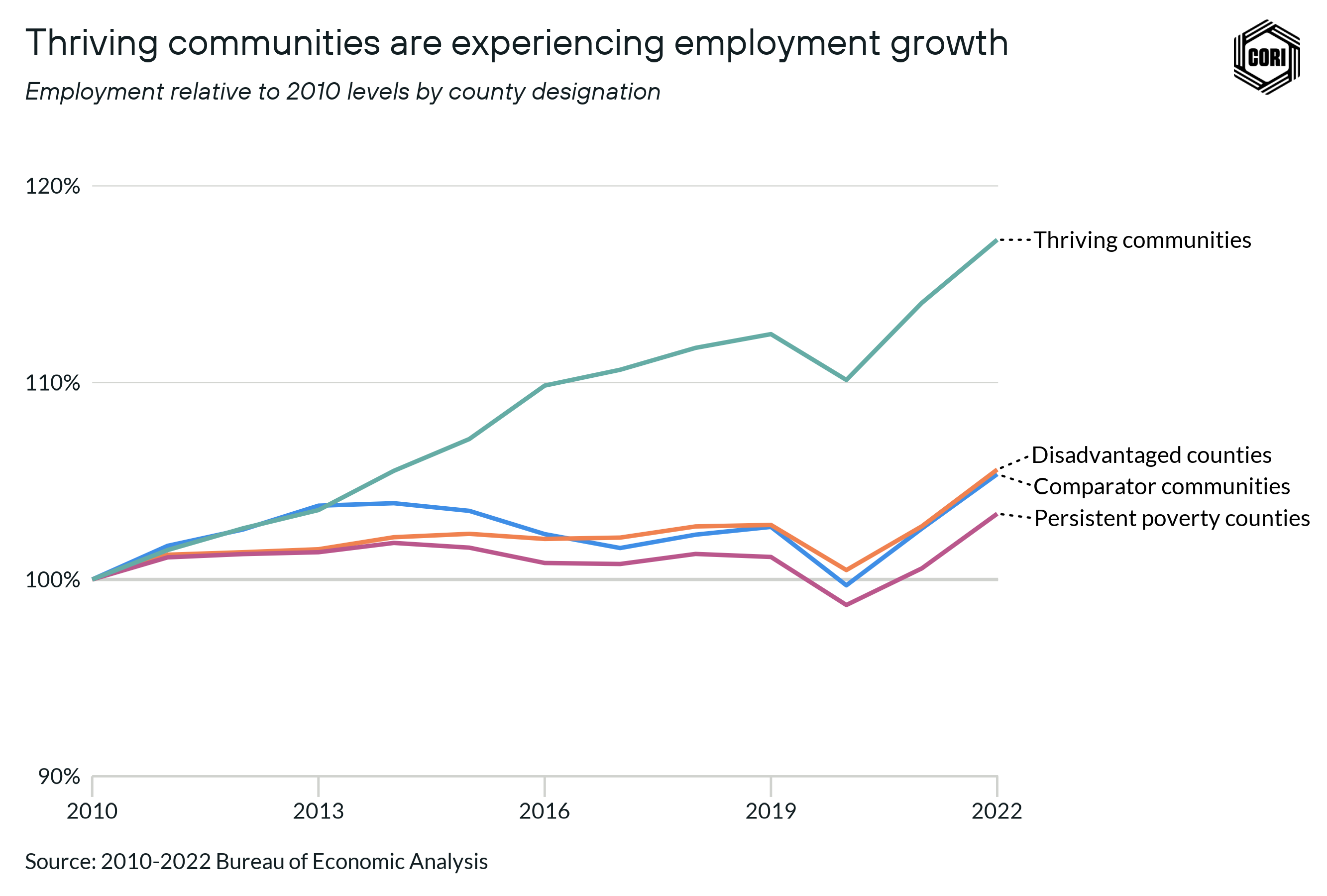

Thriving communities have seen higher job growth, progress likely in line with having built up their entrepreneurial capacity. Previous research indicates that targeted, place-based policy initiatives focusing on local job growth — such as increasing entrepreneurship and broadband access — reduce poverty, especially in persistent poverty communities where the magnitude of the impact of these programs on reducing poverty is approximately three times greater (Goetz et al., 2011, Partridge and Rickman, 2007).

The communities that are on the path to thriving have sustained job growth that would suggest many of these communities should see further improvements in reducing poverty rates and in expanding access to economic opportunities.

Insights from thriving communities and prior research shed light on how these communities sustain remarkable economic growth. Research indicates that places with greater industry diversity are more stable and resilient to employment shocks (Brown and Greenbaum, 2017; Deller and Watson, 2016).

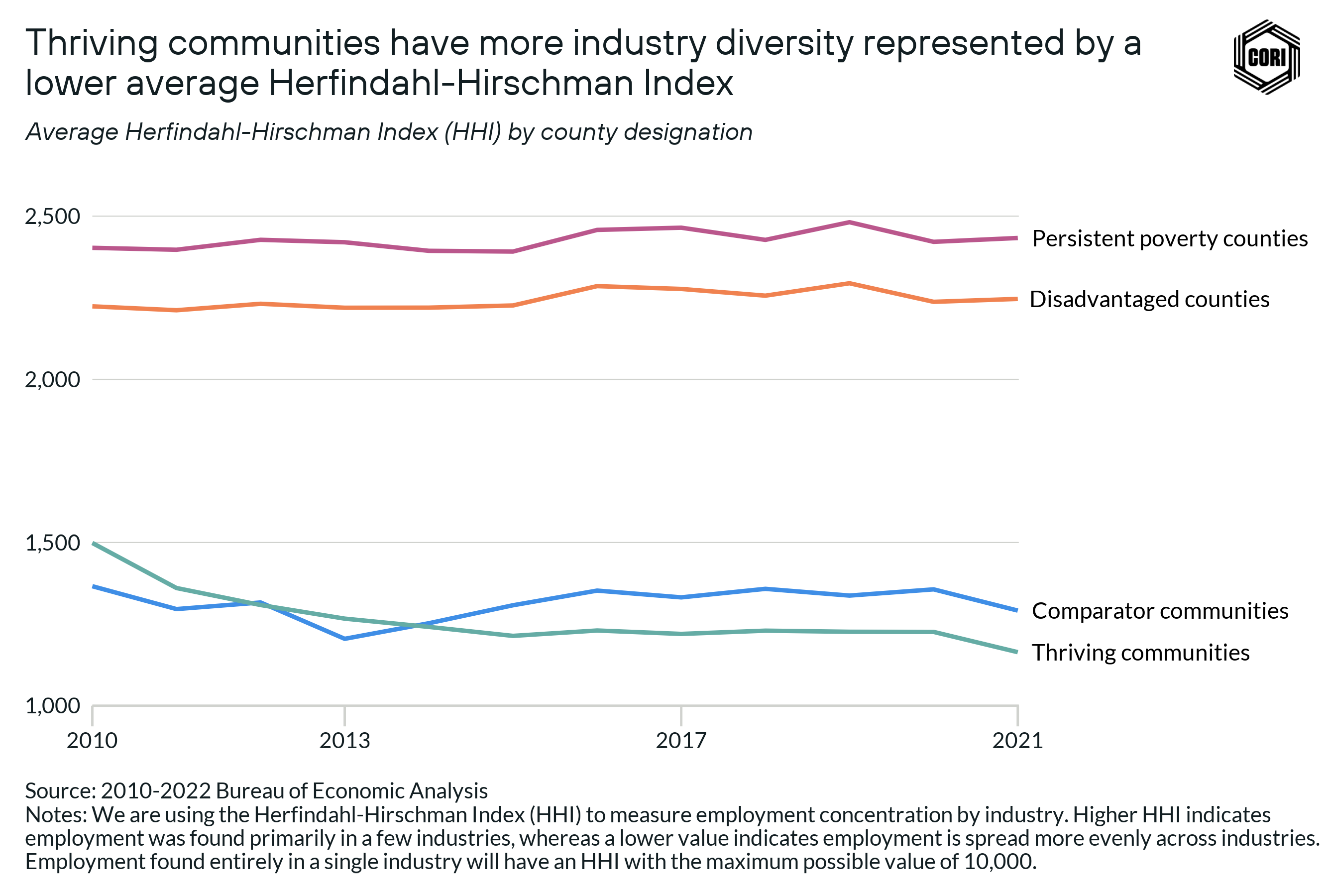

Over time, rural areas have shown increased industrial diversity, offering a broader range of job opportunities. Comparing thriving communities with other disadvantaged counties reveals an even higher level of industry employment diversity as measured using the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index where higher numbers are indicative of more market concentration and less industry diversity. Thriving communities have also become more industrially diverse since 2010.

Tupelo, Mississippi, exemplifies this by balancing traditional industrial recruitment with economic diversification strategies. This includes supporting small- and medium-sized businesses, enhancing quality of life, investing in human capital through educational partnerships, and balancing development plans with local school system needs. Alongside a significant manufacturing presence, Tupelo is the smallest city in the U.S. housing multiple banks with assets over $10 billion. This commitment to economic diversification and community development traces back to the 1940s when George McLean, a local newspaperman, began reinvesting profits into economic initiatives.

Increasing the entrepreneurial capacity of a community may help increase industry diversity and reduce the market power of any dominant firm or industry. It can also help communities pivot into growing 21st-century industries, and specifically, the knowledge economy.

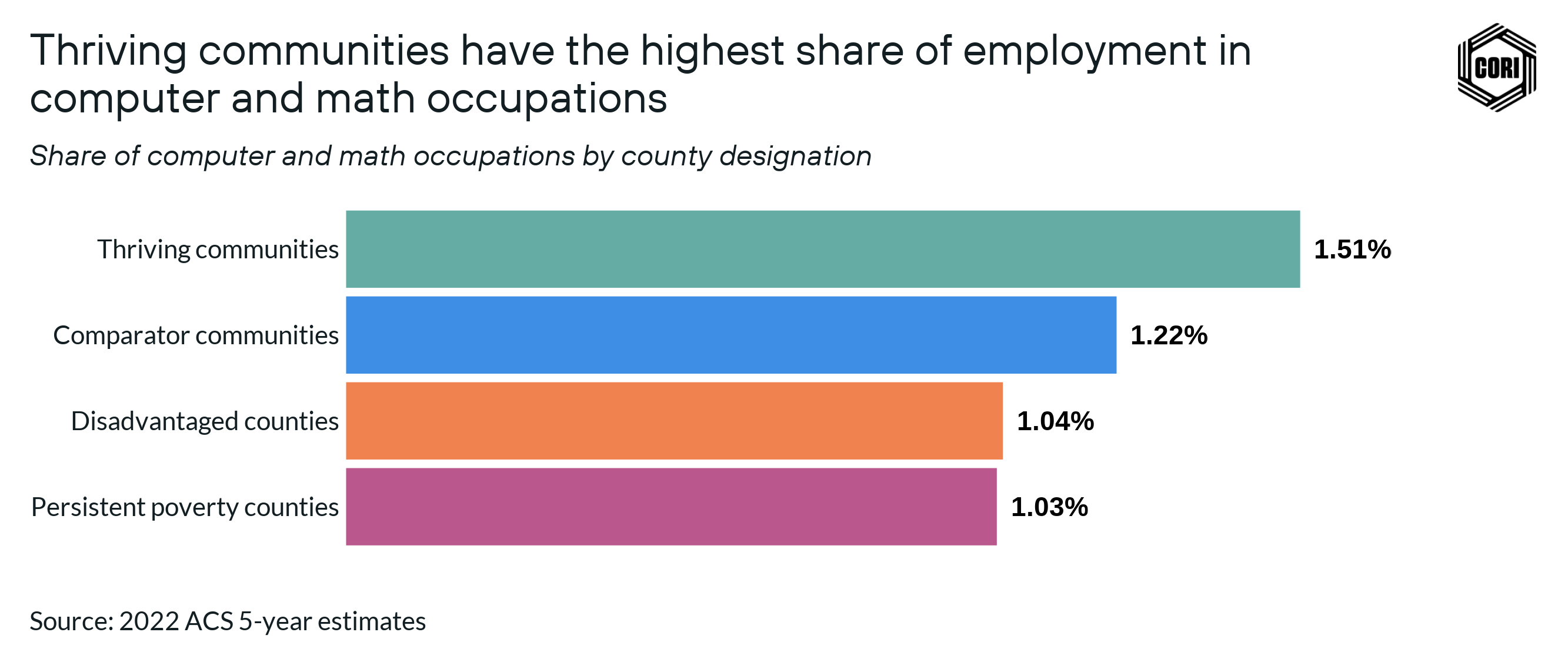

This is particularly important as Story 3 of the Rural Aperture Project showed the knowledge economy has widened the economic opportunity gap between rural and nonrural places. Thriving communities have a higher share of tech jobs (measured by the employment share of computer and math occupations), which offer higher-paying jobs with a larger multiplier effect, with the gains being shared more broadly across the community (Bartik, 2018). A larger multiplier effect means that growth in high-tech industries comes with growth in other industries as well — further increasing the impact on industry diversity and the broader community.

Coworking spaces play an important role in supporting and attracting remote workers across industries, facilitating networking, collaboration, and knowledge sharing. The coworking space in Statesboro, Georgia, emphasizes the importance of shared knowledge and community. Coworking spaces can also be vital hubs of fast, reliable broadband in rural regions where broadband quality and access can be unreliable.

The coworking space in Oxford, Mississippi, connects members to some of the fastest internet available in town. Particularly important for tech workers with the highest share of remote workers (BLS, 2022), these spaces, when linked with services like housing or childcare, reshape the perception of rural economies, making the digital economy accessible (CORI, 2021).

In addition to practical workspace solutions, coworking spaces foster educational opportunities and a sense of community among entrepreneurs. In Taos, New Mexico, the UNM-Taos HIVE recently launched a partnership with Youth Coding League, a program developed by another Rural Innovation Network community, Cape Girardeau, Missouri, to introduce 5th-8th graders to coding and computer science through friendly competition. By offering training programs, they contribute to enhancing the education and skills of the local workforce.

Increasing worker productivity is key to building a stronger, more sustainable, and more innovative economy

Education is a cornerstone of human capital, encompassing the knowledge, skills, and abilities within a community. Human capital includes both formal and informal training to develop skills and abilities. It not only contributes to individual development but also bolsters the overall economic health of a region by increasing productivity.

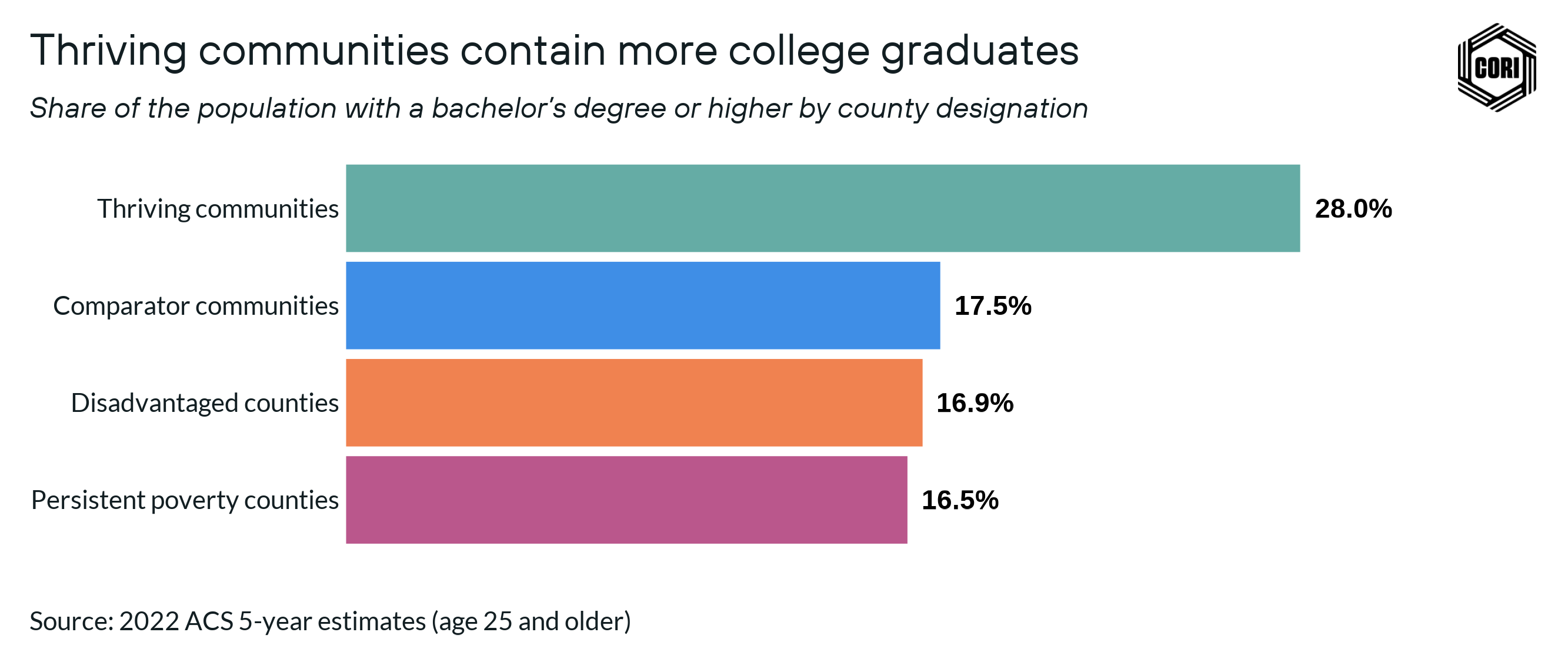

A highly trained workforce can also help communities better adapt to economic shocks. The most advantaged communities in the U.S. tend to have considerably higher investments in education and high levels of high school graduation rates and college attendance (Edin, Shaefer, and Nelson, 2023). Higher educational attainment in communities, including rural areas, is associated with higher income growth and higher job growth (Gibbs, 2005).

Thriving communities are more highly educated, as measured by the share of the population with a bachelor’s degree or higher, than similarly disadvantaged communities and most of the thriving counties have higher education institutions. For example, Oxford, Mississippi, is home to the University of Mississippi (“Ole Miss”). Sam Houston State University is located in Huntsville, Texas; Northwestern State University is in Natchitoches, Louisiana; and Georgia Southern University is in Statesboro, Georgia.

College proximity is associated with higher educational attainment, especially for students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. But that proximity isn’t the only factor: , 28.3% of the population in Tupelo, Mississippi, has a bachelor’s degree or higher — slightly above the average for thriving communities — even though Tupelo doesn’t have a traditional four-year university.

Thriving communities also have higher high school graduation rates, on average, than the comparators, with Oxford and Taos tied for the highest high school graduation rates among all of the thriving and comparator communities. Improving K-12 schools can boost the educational opportunities for students in thriving communities as well as make a community a more attractive place to raise a family. It’s also essential that quality education is accessible to all members of a community, regardless of their race or socioeconomic background: Segregated schooling systems often lead to disparities in educational outcomes and in resource allocation, which can perpetuate cycles of disadvantage.

A comprehensive and inclusive approach to education, considering its various dimensions, is essential for fostering resilient and thriving communities. The thriving communities have lower school segregation, on average, than the comparator counties (calculated using school segregation data from County Health Rankings & Roadmaps).

Research shows inclusive education produces better outcomes. For example, public school desegregation had the most dramatic effect in the South — and by 1972, the South had the most racially integrated schools. “The data show that in both reading and mathematics, at each of the grade levels tested, gains for southern Black students have exceeded those for any other category” (Wright, 2013 pg 178). After the transition to desegregation, southern Black students had dramatic gains in educational attainment and eventual earnings relative to white students with no adverse effects noted for white students (Ashenfelter et al., 2006; Boozer et al, 1992).

While Oktibbeha County, Mississippi, increased the inclusivity of its education system by consolidating school districts, Taos sought to increase accessibility to higher education by making it more affordable through New Mexico’s statewide program to cover tuition and fees at any public higher education institution for eligible in-state students.

This policy may be particularly important for rural students and students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. Research indicates that rural students tend to fall behind their nonrural counterparts in attaining bachelor’s degrees due to the constraints imposed by their comparatively lower socioeconomic status (Byun et al., 2012). In most states, school funding across rural and nonrural districts remains inequitable, limiting access to education and the ability of rural schools to adapt their curriculum to the changing needs of the economy.

To adapt to economic changes and uncertainties, communities must focus on preparing a workforce with the skills for 21st-century jobs. This involves providing educational programs through a variety of platforms. Many non-traditional education training programs are now available to help workers pivot into high-paying careers. For example, Lockheed Martin in Troy, Alabama, opened a workforce training facility while the Ogeechee Technical College in Statesboro, Georgia, recently announced the state had approved funding to construct the Georgia Industrial Systems and Industrial Robotics Training Center.

A recent task force formed by the Foundation for the Carolinas set out to discover what a community needs to improve access to economic opportunity and “identified early childhood development, college and career readiness, family stability and strong social networks as key factors that enhance upward mobility. It singled out segregation as a key obstacle.” (Ydstie, 2018).

Despite progress in many of these areas, many thriving communities still lag in early childhood education access. This issue, prevalent in disadvantaged rural areas, widens the rural-nonrural gap. One exception, Troy, Alabama, a thriving community, has improved access to quality early childhood education through the state’s First Class Pre-K program, targeting poor counties and expanding successfully since 2000. “[Alabama] has targeted some of the poorest counties in the state — especially those in the Black Belt. And according to the latest in a series of issue briefs on the region from the University of Alabama’s Education Policy Center, these strategies have worked” (Archibald, 2022).

Improving access to economic opportunity likely starts from birth and extends beyond graduation.

Quality of life helps keep and attract families and businesses

“Recognizing that knowledge will likely remain the catalyst for economic growth and innovation, regions with an attractive quality of life for high-skilled workers will have an advantage.” (Partridge and Olfert, 2011)

When innovative entrepreneurs were asked what attracts them to a location, they responded by saying they were attracted to a location that had talented workers and the quality of life these workers like (Endeavor, 2014). Small towns (micropolitan areas) with higher estimated quality of life are associated with higher population growth, higher job growth, and larger drops in poverty rates (Weinstein, Hicks, and Wornell, 2022).

Additionally, quality of life and a highly skilled workforce have even larger effects on growth for rural areas, and there is a positive interactive effect between the two (Fan et al., 2016). Thus, quality of life — which encompasses various factors influencing an individual’s overall well-being and satisfaction with life in a community — is likely more important for rural areas.

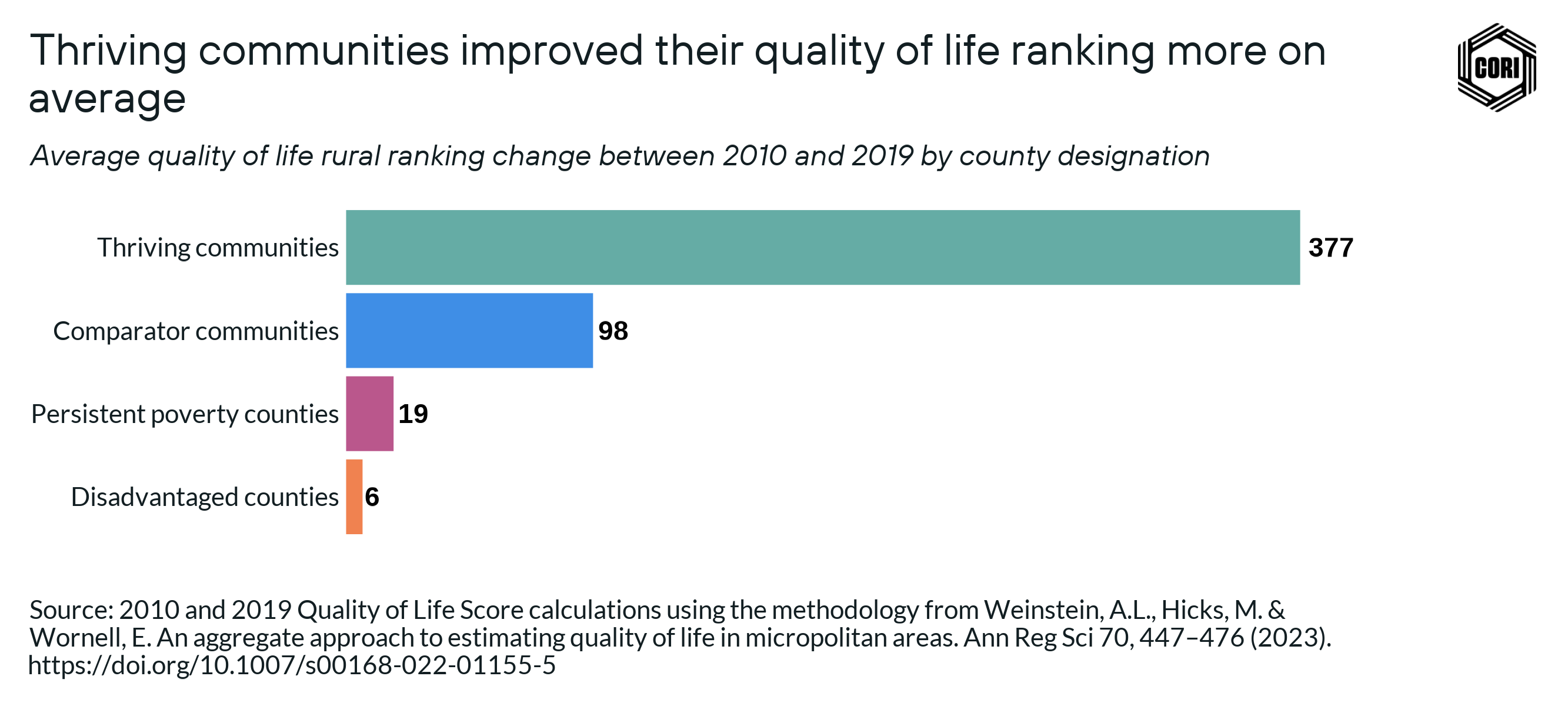

We examined quality of life metrics for the thriving and comparator counties (using the methodology from Weinstein, Hicks, and Wornell, 2022 to estimate quality of life). This helped us gauge the improvements or declines in quality of life over time.

Thriving communities have higher estimated quality of life, on average, than their comparators and larger improvements in quality of life since 2010. Thriving communities saw improvements in their quality of life that were over 2.5 times higher than the quality of life improvements for the comparator counties, which significantly improved their quality of life ranking among 1,920 rural counties across the country.

Taos, known for its ski resorts, stood out as the top-rated thriving community for estimated quality of life in both 2010 and 2019. Taos is the only thriving community in our sample that is considered a “high amenity” county according to the USDA’s natural amenity index. Yet, other thriving communities are capitalizing on the natural amenities they have.

Natchitoches, Louisiana, has been leveraging its history as the oldest town in Louisiana and its scenic river location to become a popular tourist destination, boosting bed-and-breakfast inns (now hosting the most in the state). Natchitoches has also been named an ideal place to retire and the best small town in the state. The community has capitalized on Cane River Lake, which has become a key spot for university sports teams’ training, as well as for fishing, boating, and kayaking.

Successful community development in Taos has relied not just on natural amenities but on how these assets are leveraged. Taos is building on its scenic beauty and recreation by investing in the community, creating a unique downtown that also attracts people — and expanding economic opportunity by creating high-paying tech jobs through education, entrepreneur programming, and mentorship that help support the vibrant downtown.

“Everyone deserves access to a vibrant community: A place with a thriving local economy, rich in character, and features inviting public spaces that make residents and visitors feel they belong. Our mission is to facilitate a shared vision for our downtown, to encourage economic vitality, and to celebrate Taos’ cultural and historical assets.” (Taos MainStreet)

Efforts to revitalize downtown Starkville include engaging the public in setting priorities, such as through a street safety survey on the city’s website. This initiative reflects a commitment to public participation in urban planning. Furthermore, the city has been investing heavily in parks and recreation, funded through tourism sales taxes. This investment, amounting to approximately $2.5 million annually, indicates a strong commitment to enhancing community spaces and quality of life.

Similarly, Troy’s decade-long downtown improvement project, funded by community development block grants and guided by community input and placemaking best practices, aims to transform a historic Academy Street high school into a vibrant hub, reflecting a trend where quality of life enhancements signify strong leadership and community engagement.

Although Taos has the highest estimated quality of life among the thriving and comparator communities, Oxford has experienced the largest increase in estimated quality of life between 2010 and 2019.

Thriving communities (and economies) are built on a solid foundation of assets that we at the Center in Rural Innovation refer to as “foundational elements.” Local talent needs affordable housing, access to education and healthcare, vibrant workspaces, and lively downtowns. Public sector support, in partnership with private, nonprofit, and higher education sectors, is vital for coordinating these efforts to improve quality of life.

Many of the amenities associated with higher quality of life (or improved conditions of place), including higher public school spending and programs to increase mobility, also promote the success of all residents (Weinstein, Hicks, and Wornell, 2022). That success, including access to economic opportunity, in turn, provides further support for local businesses that improve quality of life.

Healthy communities are stronger communities

There is a wide literature on the relationship between health and wealth, showing that better economic standing increases health outcomes across the income ladder (Finkelstein et al, 2022; Woolf et al, 2015). And that better health outcomes increase the productivity of workers, which in turn improves economic outcomes (Raghupathi and Raghupathi, 2020). Better health outcomes are also associated with higher estimated local quality of life (Weinstein, Hicks, and Wornell, 2022).

Although the health equity considerations are vast, in our analysis we examined factors that would help us gauge the health status of communities, recognizing its critical importance in both community well-being and long-term sustainable economic development.

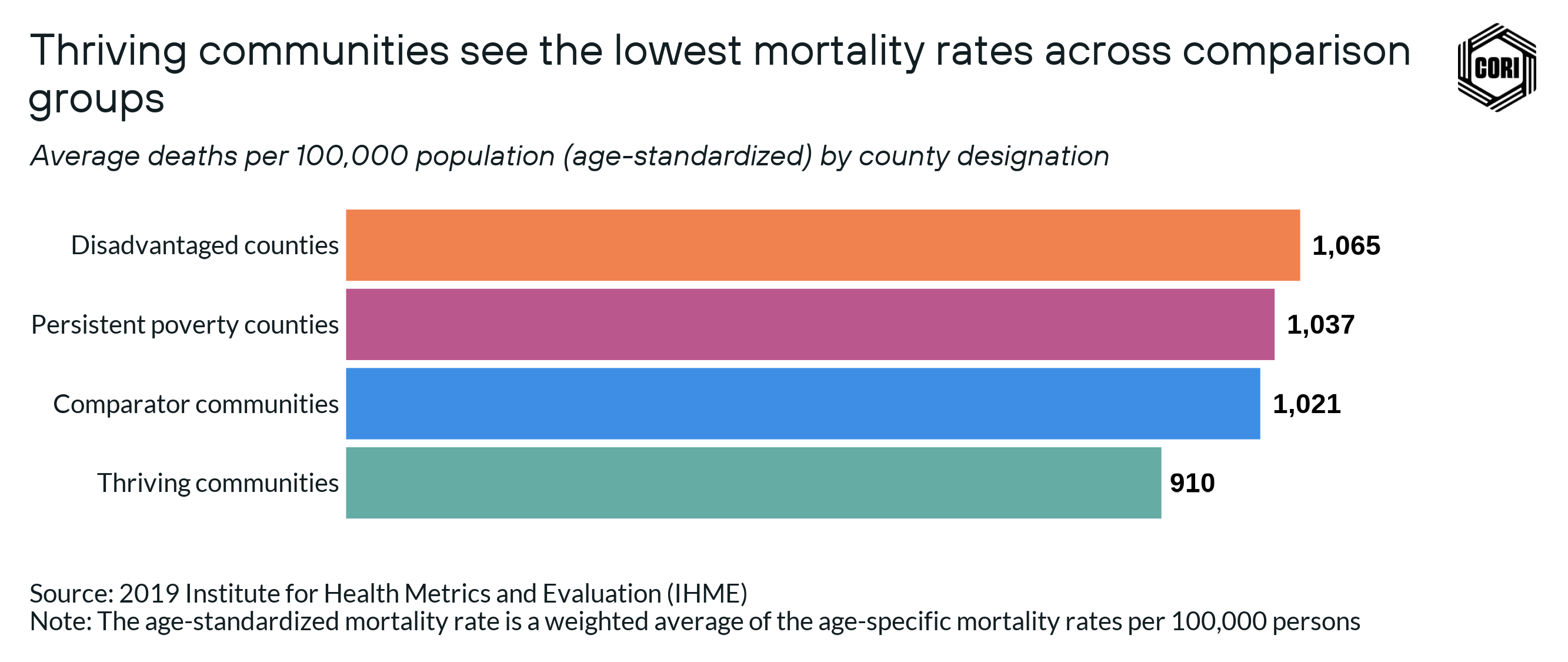

We found the thriving communities’ self-reported health metrics were higher than the comparators, yet they still lagged behind in the share of uninsured residents (County Health Rankings). The thriving communities also showed lower mortality rates compared to all other groups. The mortality rate is important because it is an indicator that helps us understand the overall health of a population, and is also consistent with our expectation that better economic indicators would coincide with better health outcomes. High mortality rates might indicate health problems or poor living conditions in an area, while low rates often suggest better health and living standards.

Disparities in health outcomes across rural and nonrural places are driven in part by access to medical facilities (Probst et al., 2019). Rural areas, particularly those with shrinking tax bases and dwindling populations, have been disproportionately affected by healthcare consolidation and hospital closures.

This is also an important equity concern because it is a particularly vicious cycle that continuously impacts race, place, and class: The economic challenges in rural areas, often worsened by the policies and economic trends that don’t favor them, as we discussed in Story 3 of the Rural Aperture Project, significantly impact their ability to keep hospitals running. Research also suggests that these hospital closures disproportionately impact rural people of color, with a higher proportion of rural hospital closures taking place in micropolitan or small towns compared with isolated rural areas (Thomas et al., 2016; Kay, 2023).

The closure of these facilities can negatively affect communities in various ways. Not only do rural hospital closures limit access to essential health services, forcing residents to travel greater distances for critical care, but they can also result in significant economic repercussions. The loss of healthcare jobs and related economic activities can impact the economic vitality of these communities, and the people who remain in rural areas are often lower-income, older, sicker, and may have less insurance coverage. This results in a less favorable payer mix for hospitals, as Medicare and Medicaid typically reimburse less than private insurance, leaving hospitals struggling to remain financially viable (Gujral & Basu, 2019).

Unsurprisingly, each of the thriving communities we’ve highlighted has a hospital or medical center.

Investment in healthcare has a significant impact on the broader well-being of a community. Efficient and accessible healthcare services attract residents and businesses, contributing to the overall economic stability and growth of the area. Robust health systems are a cornerstone of thriving communities, offering both direct and indirect economic advantages.

There are many social and economic factors, and local factors that affect health outcomes — income, human and social capital, environmental quality, and safety among them. Using a variety of social and economic conditions that predict long and healthy lives specifically for Black Americans, data from the Black Progress Index indicates that the thriving communities have, on average, higher predicted Black life expectancy than the comparator counties. Various conditions of place in thriving communities have laid the foundation for better long-term health outcomes for the broader community.

Inclusive growth benefits the entire community

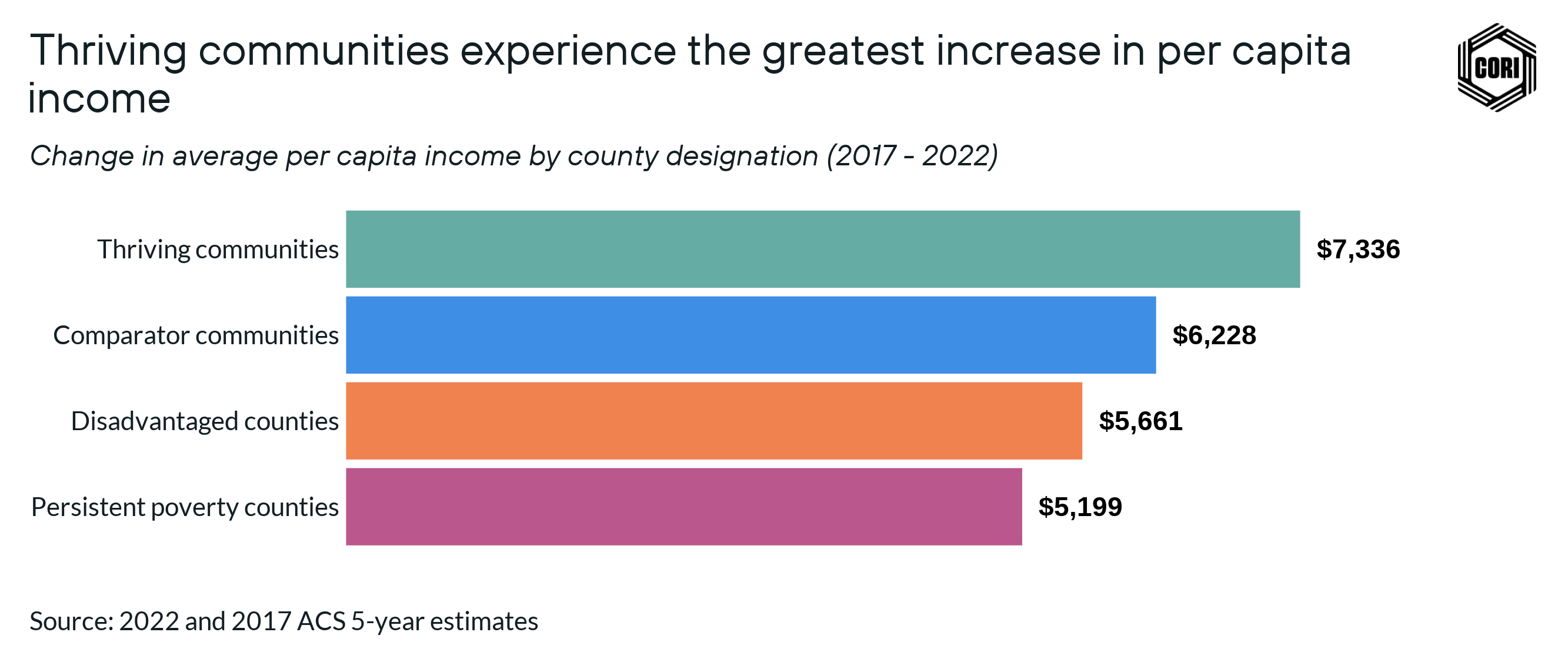

Thriving communities appear to be on a path of steady growth, despite their disadvantages. A comparison of the thriving communities shows that they are also experiencing higher income growth. Yet, this higher income growth has not been accompanied by growth in inequality — the opposite in fact.

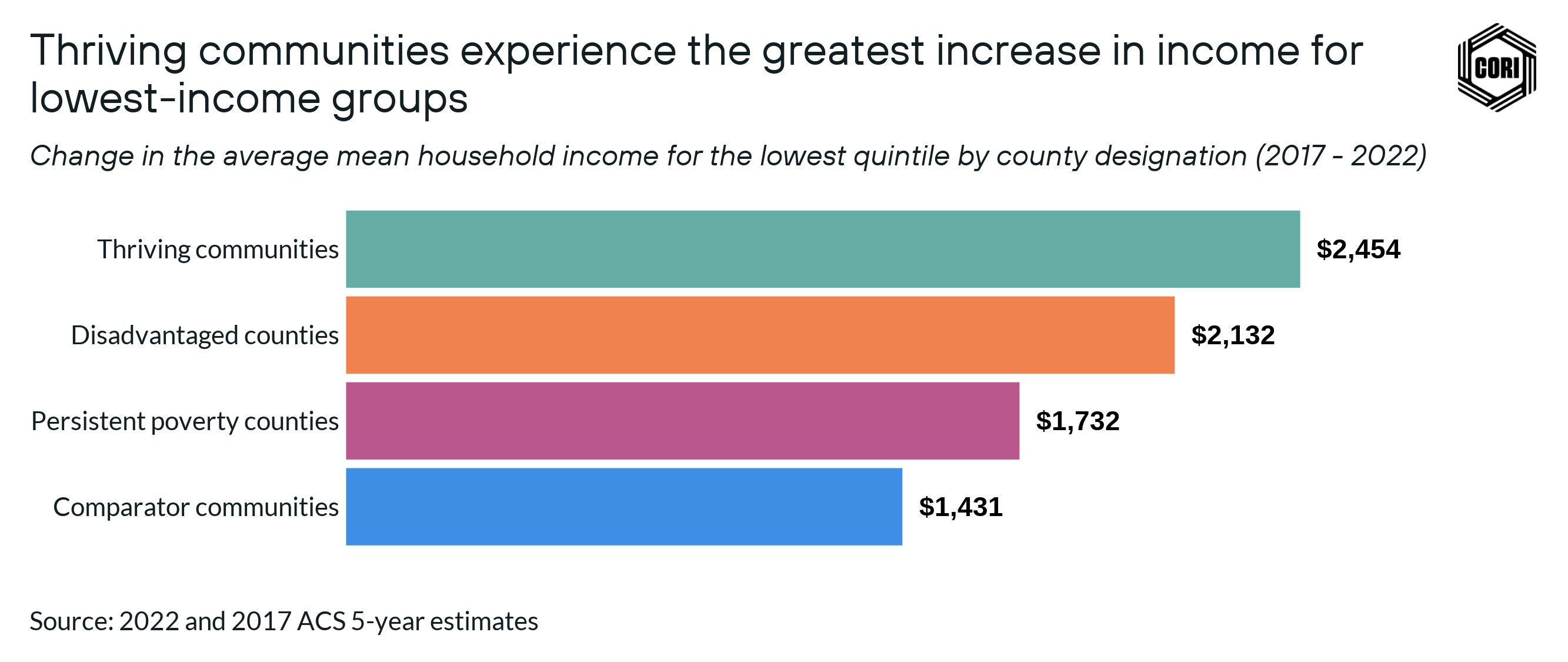

Despite income growth in the highest quintile of earners in the thriving communities, incomes grew at an even faster rate for the lowest quintile.

In the thriving communities, the highest income quintile saw an average increase in their income of 26.6% (16.4% in the comparator counties) while the lowest quintile saw income gains of 29.5% — nearly three times greater than the 10.4% growth seen in comparator counties (ACS, 2022 compared to ACS, 2017 five year averages).

Indeed, the thriving communities seem to be growing without leaving people behind. This is especially important as income inequality can diminish the poverty-reducing impacts of economic growth (Nasir, 2017).

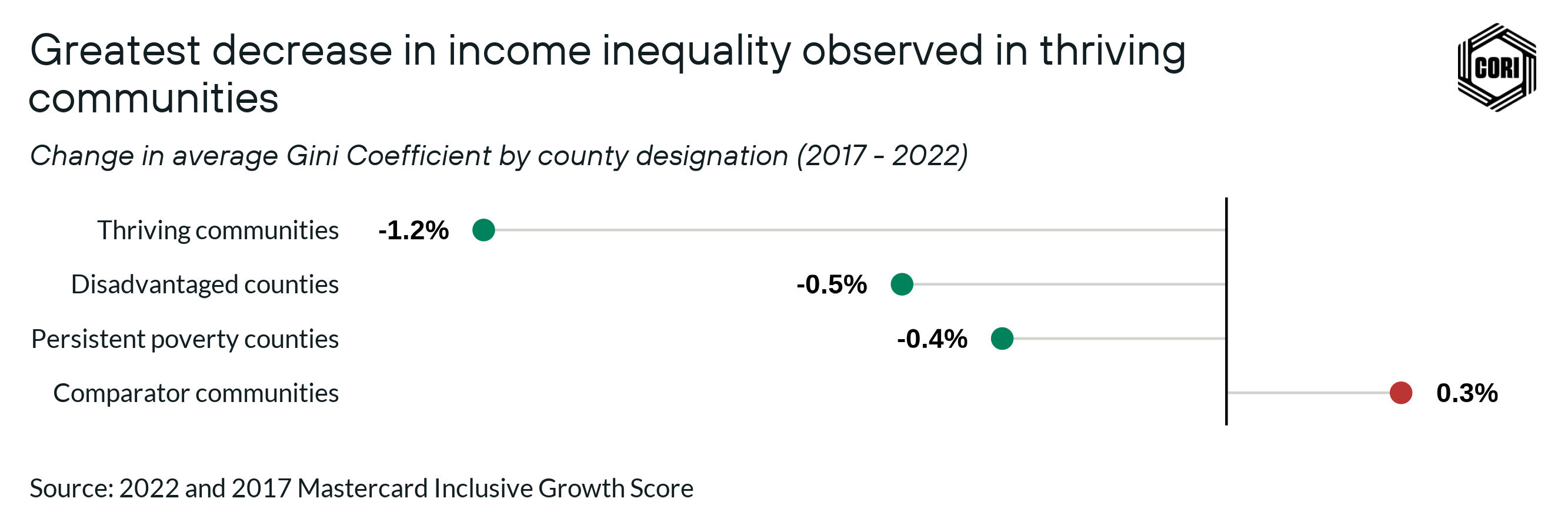

The thriving communities have experienced the greatest decrease in inequality among other disadvantaged places as measured by the Gini coefficient, a metric often used to analyze the income distribution or wealth disparity among a population where a higher index indicates more inequality. Thriving communities also have lower neighborhood segregation in addition to lower school segregation, on average, than the comparator counties (calculated using segregation data from County Health Rankings).

Inclusive growth helps ensure that economic development benefits everyone, especially those in the lowest income bracket. For communities with persistent poverty, it is also indicative that they are on their way toward exiting the persistent poverty category. Research indicates that more equality, along with investment in education and high social capital are common in the most advantaged communities.

The thriving communities tend to have an approach to economic development that is more inclusive not only within their communities but across the region. For example, Mississippi has The Golden Triangle which refers to the region in the northeastern part of the state that encompasses three cities — Columbus, Starkville, and West Point — highlighting the collaborative efforts aimed at fostering economic prosperity and job creation in the region. In Troy, Alabama, a regional and more cooperative approach to economic development is often touted:

“In interviews of business, political, and economic development leaders, there is a widespread recognition of the need for regional cooperation around economic development and a willingness and desire to move toward that goal.” (Spencer)

A regional approach to economic development can help places leverage each other’s strengths to grow together rather than compete against each other for jobs. “Economic development — especially regional economic development — matters. It matters because it is place-based, responsive to geographic inequality, and comprehensive in scope,” one of three key points made by Amy Liu testifying to the U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works on Economic Development Administration programs.

Conclusion and recommendations

This final story of the Rural Aperture Project focuses on deeply disadvantaged rural communities and micropolitan areas that are on the path to thriving, showing signs of long-term sustainable economic growth.

These thriving communities, often lost in the narrative of widening rural-urban gaps, show progress in many areas that research indicates can profoundly impact economic conditions and access to economic opportunity by diversifying their economies, many through developing a knowledge economy and support for local entrepreneurs, investing in infrastructure and improving access to healthcare and access to educational opportunities and workforce skill development while improving quality of life in their town.

Many thriving communities we studied likely owe their success to long-term grassroots initiatives with visionary institutions and leadership that led to targeted investments in the community:

- Tupelo’s transformative journey began with George McLean’s work in the 1940s to diversify local economic production and bridge the gaps between rural and city work, leading to the creation of the CREATE foundation that still invests in education and community development initiatives today.

- Wilson, North Carolina’s commitment to public utilities and investments in infrastructure dates back to 1890, evolving into a state-leading municipally owned broadband service.

- Taos’s Kit Carson Electric Cooperative, operating since 1944, has a long history of community service and commitment to sustainability, recently 100% daytime energy from solar power for their members. Similarly, Kit Carson Electric Cooperative not only provides accessible utilities to the community but also invests in resources for making the knowledge economy more accessible like the UNM-Taos HiVE.

- The T.L.L. Temple Foundation in rural East Texas, established in honor of the Southern Pine Lumber Company founder, has a mission to “work alongside rural communities to build a thriving East Texas and to alleviate poverty, creating access and opportunities for all” through philanthropy. As Jerry Kenney with T.L.L. Foundation puts it, “Philanthropy must prioritize the work of revitalizing and building new rural institutions that will power success in place.” Their work to revitalize and build new rural institutions includes support to develop the tech ecosystem in Nacogdoches, Texas.

But their work is not done. Continued investment is likely necessary to stay on the path to thriving. Many rural communities that have fallen behind will also likely need the resources and funding to improve access to economic opportunities within their community. But our final story of the Rural Aperture Project showed it is possible for deeply disadvantaged rural communities to make real progress.

We examined rural communities on different paths to thriving, yet we also need more research into the specific community-centered economic development strategies that will be most effective given the unique challenges and strengths of each community. Further research into effective funding sources (both public and private) and policies for place-based economic development in disadvantaged rural areas is essential to build out leadership capacity and turn data into actionable strategies to propel these communities forward.

Contributors

The Rural Aperture Project represented a true team effort. This story would not have been possible without the contributions of Camden Blatchly, John Hall, Brittany Kainen, Olivier Leroy, Dolley MacDermot, and Drew Rosebush from CORI’s data team.