Portraits of a community: Portsmouth, Ohio

In a past life, Portsmouth, Ohio, bustled as one of the towns making the steel that fueled America’s booming auto industry.

Its population swelled to more than 40,000. Manufacturing operations thrived in its mills and factories. Its riverfront stadium was home to what is now the fifth-oldest franchise in the National Football League — a team better known today as the Detroit Lions.

But times changed. The professional football team left for the Motor City in 1934. The steel and iron operations that brought 20th-century prosperity to the city at the confluence of the Scioto and Ohio rivers slowly disappeared in the decades that followed, a good chunk of the population going with it.

In recent years, though, Portsmouth and its 18,000-plus residents have begun to establish and embrace their own niche in the digital economy of the 21st century.

The handsome old building that once housed a clothing factory has been reborn as the Kricker Innovation Hub, a forge for scalable startup activity. The local college, Shawnee State University, is home to one of the Princeton Review’s top 10 video game design programs in the country, positioning its students on the cutting edge of digital creativity and production. And nearly 100 years on from Portsmouth’s time as an NFL city, it is home to an entirely new type of competitor — esports athletes who are flourishing as part of the area’s gaming culture.

That’s why the Center on Rural Innovation visited Portsmouth for the fourth piece in its “Portraits of a community” series — our first installments featured Taos, New Mexico, Springfield, Vermont, and Ada, Oklahoma. These stories are intended to shine a light on the people who make up the unique ecosystems within CORI’s Rural Innovation Network, which connects rural leaders and advocates around the country to accelerate their learning and amplify their work on the ground.

Andrew Feight

Developer and Editor, Scioto Historical

Two decades after he arrived in Portsmouth to teach history at Shawnee State University, Andrew Feight is using 21st-century tools to breathe new life into the area’s past and make it more accessible than ever. A tenured professor of American and digital history, Feight’s scholarly research drove the establishment of the Shawnee Digital History Lab in 2005 and its growth into the school’s Center for Public History, opening this fall. But where many would’ve simply channeled their research into book, Feight saw an opportunity to go further, go digital. He lined up local grants and secured a license for a platform originally developed at Cleveland State, then set to work building what is now the Scioto Historical app and website. When Feight is away from campus, he and his wife, also a professor at SSU, enjoy tending to a large garden and raising poultry at their home in the forest outside of Portsmouth

“The reach that it has is really showing the potential for public history. I can type up a journal article and send it off to the Register of the Kentucky Historical Society or the Ohio Valley History Journal and maybe 300 people might read that. And, you know, maybe there’s 30 libraries that have subscriptions to it, right? Then it’s behind a paywall when it actually is digital. And so this is really a champion of public history, of open access.”

“I think this public history type of work and platform enables the people of the community to tell their own story. And in the process of doing that, it actually shows you the diversity of the history … looking at the history of the black community, the history of segregation, the history of the Underground Railroad here. We’re also developing a whole new tour, with multiple historical sites, looking at the civil rights movement. A lot of people don’t realize that communities in Ohio also had segregation and so there was a local civil rights movement, a local NAACP chapter, there were numerous campaigns, civil disobedience, direct actions that were taken that helped break down Jim Crow. Now that story has never really been told, and the technology that we have today, I think, really is going to have an impact on how we’re able to tell these histories.”

“I think that it has the potential to improve and to encourage cultural heritage tourism, but also to sort of push back about some of the narratives and stereotypes and so forth that tend to lead people to believe that Appalachia is White, you know, and, and to see the diversity that we have here. Now for within the community, though, I think having a sense of one’s own past and having some pride in your community … I have students all the time that say you know I grew up here and I’ve never heard this before.”

Kyle and Shannon James

Co-founders, The Vault

Before his career two decades ago as a nationally ranked Counter Strike player who traveled across the country and the globe for competitions, Kyle James was a kid from Portsmouth who needed a ride to Louisville, Kentucky, to find out how good he was. Now the entrepreneur and his wife, Shannon, a trained nurse, are starting an esports gaming center called The Vault — one of three businesses they’re launching side-by-side — that would eliminate that barrier to entry for gamers in their hometown. They envision The Vault as a place that can connect Portsmouth’s entire gaming community and also, potentially, become the type of competition venue that local talent would otherwise need to travel to Cleveland or Nashville to access. In time, the couple hopes to make the experience even more approachable with free play days and bring-a-friend days.

Kyle: “When I was a gamer in the 90s I had this thought for a gaming center where kids come and game on computers and consoles — not your typical arcade. At the time, internet cafes were just starting to appear, no one had ever heard of them, and nobody had heard of gaming center. So at 14 I wrote this whole big plan out, and then when I turned 18 I actually went with my aunt to see about getting funding. And the banks laughed at us. They thought this was the stupidest thing they’d ever heard of. Nobody was gonna fund this. Well, you fast-forward now, 20-some years later, and now, banks and anybody else, are wanting to get in at the ground floor.”

Shannon: “It’s sort of all been able to come together for us. Obviously his strengths are the computers and the gaming, and then I sort of have the complementary skill set to run a business. … There were buildings downtown that I love and I would love to bring back to life, and then also we’re hoping to bring around 30 jobs or so into the downtown. We’re right here next to Shawnee State University … it’s literally across the street. So it’s sort of like all the pieces fell into place at the right time. The buildings were available. Our schedules allowed for it. There’s high school teams around here that are starting to do esports teams, the college is booming.”

Kyle: “Anybody can come in off the street and we will have roughly 45 PCs, 20 consoles, and then we’ll have a couple VR stations. We’re also doing a VR movie theater for parents that don’t really understand gaming, but they wouldn’t mind watching a movie while their kids play. That’s like the first layer. … The second layer is local tournaments. We’re going to have an everyday tournament where kids can come in and show how good they are, win prizes and stuff like that — your typical Fortnite, your fight games, your Madden (football). … The third layer is we’ve already had talks with the college about bringing in their gaming team, because right now they don’t have a place for spectators — whereas we’re providing a space, private space for the gamers, and then we can turn our whole facility where all the TVs, all everything flips to their monitor so, you know, young kids can watch these college esports athletes actually play matches and cheer for them.”

Shannon: “A lot of the kids, they don’t have the means to travel, and they don’t have the money or the means to upkeep their gaming computers at home, so we can provide the gaming computer and the upgrades as they as they come along, and give them an opportunity that they wouldn’t otherwise have. … And we’re hoping to provide for everybody so if someone just wants to come in and try it out, they can, you know, pay the small fee for just an hour and see if they like it. If someone already knows that they want to do it, they can get a membership and buy the passes. We want to make sure we have something for every level of player, and every price level.”

Keith Monihen

DevOps Engineer, Gaggle

Keith Monihen knew the remote work lifestyle before most Americans knew what remote work was. First as a software developer, then as a systems administrator, and now as a DevOps engineer — a solutions-oriented role that combines both backgrounds — for the student digital safety platform Gaggle, the Huntingdon, Pennsylvania, native has held distributed roles with multiple companies. That allowed Monihen and his wife to not miss a beat when they moved to Portsmouth for her job at Shawnee State University. The small-town lifestyle there — and a tech-based career — has allowed Monihen the flexibility to tackle home renovations, pick up golf during the pandemic, and get involved in their new community.

“I like the small town atmosphere. I grew up in Huntingdon, Pennsylvania, a small, small town there. Being small, it’s easy to get to know people, you can get plugged into communities. We do a lot of volunteering and giving back to the community, so it’s pretty easy when it’s a small, small town to get involved. … I think just in general, networking in small towns is pretty easy. It’s easier to, you know, find the people that you need to talk to about certain things or at least you know somebody who knows somebody to do something or to get in contact about something.”

“I’ve worked remotely since 2008 — every job I’ve had since (2008) has just been remote work. … Back in 2008, my plan was to just quit my job and go back to school. But when I told my company that I was going to do that, they didn’t want me to leave. They said, ‘You know, let’s work something out where we can get you working remotely.’ I worked for an internet hosting company so it was pretty easy for them to get that all set up logistically.”

“I’ve been into computers since the 90s when I was a teenager and started kind of tinkering around with programming stuff. I originally went to college, and I was thinking I want to get into graphic design, but I guess — fortuitously, maybe — I couldn’t get into that program because I needed a portfolio, so I just decided to do computer science and decided I really liked it.”

Audrey Schiesser

Owner, Local Happenings

What’s going on in Portsmouth and the rest of Scioto County? That’s what Audrey Schiesser wants you to know with her mobile app and events platform, Local Happenings. What started as an idea her husband, Ryan, an intelligence specialist in the U.S. naval reserves, brought back from his time interning on Capitol Hill became a way they could help people in the area access to the wealth of activities and events their hometown has to offer. The couple found a developer to build the app and have used their deep local roots — as area natives, alumni of Shawnee State University, and active members of their church community — to establish a foundation of information and users. Along the way, Audrey also managed to launch a complementary startup, Appalachian Marketing and Media, to help connect local businesses to digital markets in other ways.

“We were getting the events platform up, we were getting the businesses up on the business listings part of the app. But then we were realizing that a lot of people don’t have a social media presence or web presence, or really know how to do any type of marketing. And I graduated with my marketing degree from Shawnee. That kind of sparked Appalachian Marketing and Media to where we decided to help companies get into the digital age. So anywhere from websites, photography, videography, to managing social media accounts, creating social media accounts, anything like that — really just trying to be an all-encompassing marketing company that can help people get started or continue growing in whatever way they would like to.”

“I’ve had a couple different majors. I started off pre-med, and then realized I wasn’t really happy in that. And then I went to psychology, I wasn’t happy in that. … Not knowing what I wanted to do sparked Local Happenings. That sparked my idea of, ‘Okay, I really love doing this stuff — I love photography, videography, marketing in general.’ And so that’s kind of where I realized that this is what I love doing, and this is what I want to continue doing. It definitely wasn’t in the plans. But, you know, by the grace of God, this is what we’re doing now. And this is, you know, I think, what I’m supposed to be doing. … I wanted to be my own boss. And so founding the company was kind of the only way that I could really have that freedom to be a business owner, but also be a wife and a mom, and, you know, be my own boss on the business side of things.”

Kyle Trapp

Account Executive, LeagueSpot

Portsmouth’s gaming culture has grown up before Kyle Trapp’s eyes — because he grew up with it. Born and raised in the town where the Scioto and Ohio rivers meet, Trapp was around the gaming program at Shawnee State University, where his dad worked, played and competed in esports in middle and high school, studied game design at SSU, and went on to coach the college’s esports team for a time. After striking out on his own as an esports consultant and taking some freelance projects, Trapp joined LeagueSpot, where he works remotely to organize and support tournaments on their platform. He’s seen the world and considered moving at one point, but kept finding new reasons to stay a part of the community he knows so well.

“The culture at Shawnee State was gaming. They’re not a film school, they’re not a sports school. No matter what you could always go somewhere and talk about a video game, walk through the UC — the University Center — and there’s people playing games, you know, 24-7. Even some of the sororities and fraternities are having gaming tournaments throughout the year. So it’s literally a gaming school, and it’s so cool to see: You have basketball players playing with people you would never see playing games together, but they’re always around, you know, joking and talking — that was the thing with esports, that they were they were a part of athletes on campus.”

“When I was coaching at Shawnee, I didn’t play games, I had to get away because I was always coaching, doing things. Now where I’m doing more of my 9-to-5, and I’m done, I can play games. And what’s great is the culture of where I work is we’ll play games, like every Thursday night … but as far as the whole competing thing, those years are behind me, but I’ll still get the urge every now and then I’m like, oh, let’s go do some ranked matches and see what we’re at.”

“In 2019, the top viewed events in the world (were) the World Series, the Super Bowl, and the League of Legends final. That was one of three of the biggest-viewed events in the world at that time, and it was on Twitch, ESPN had coverage — you see ESPN showing eSports here and there. … With what I’m doing currently, I’m working more with youth programs and seeing everything, and it’s NBA, Fortnite, Rocket League, and Smash Brothers — there are kids non-stop competing in those.”

Paul Yost

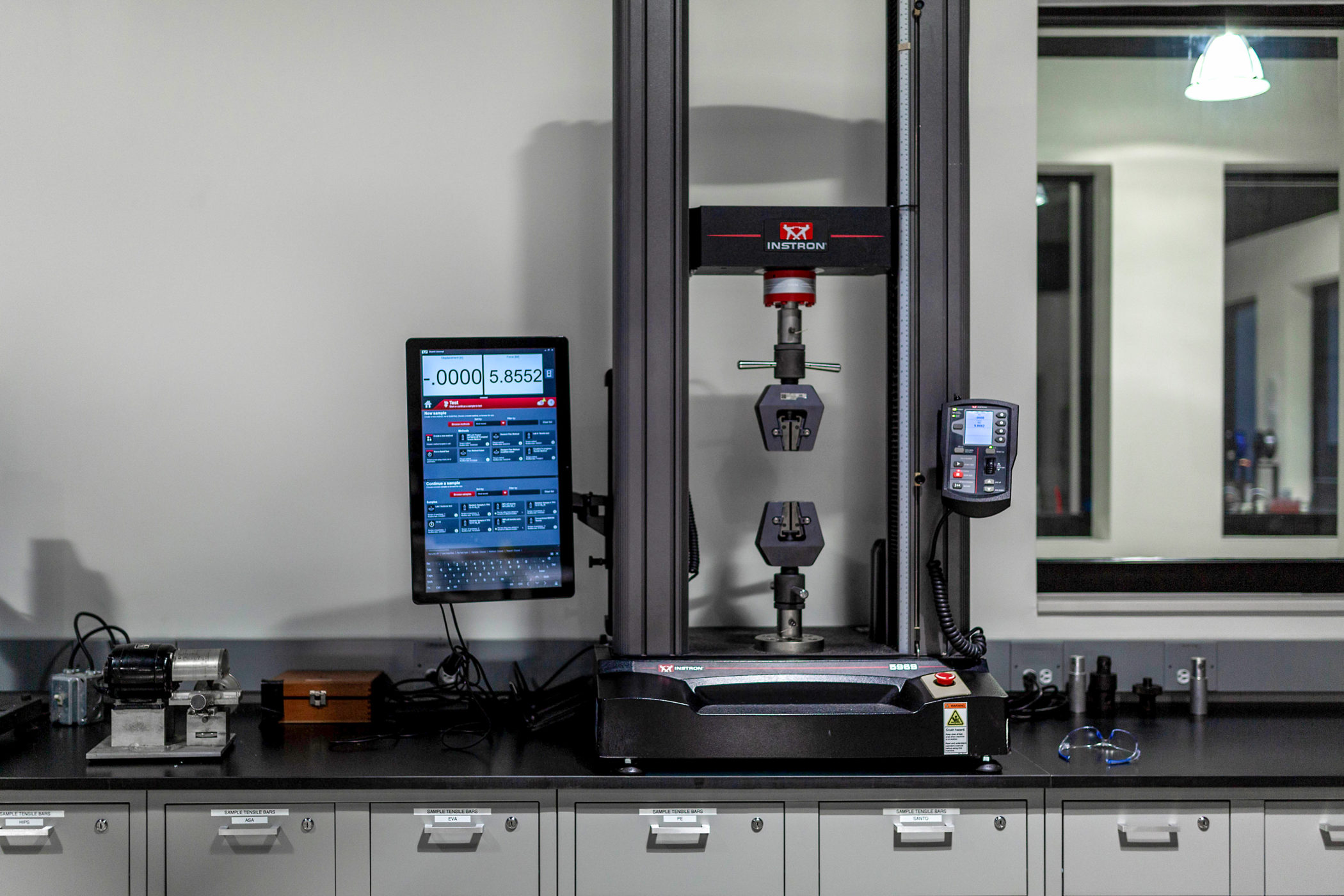

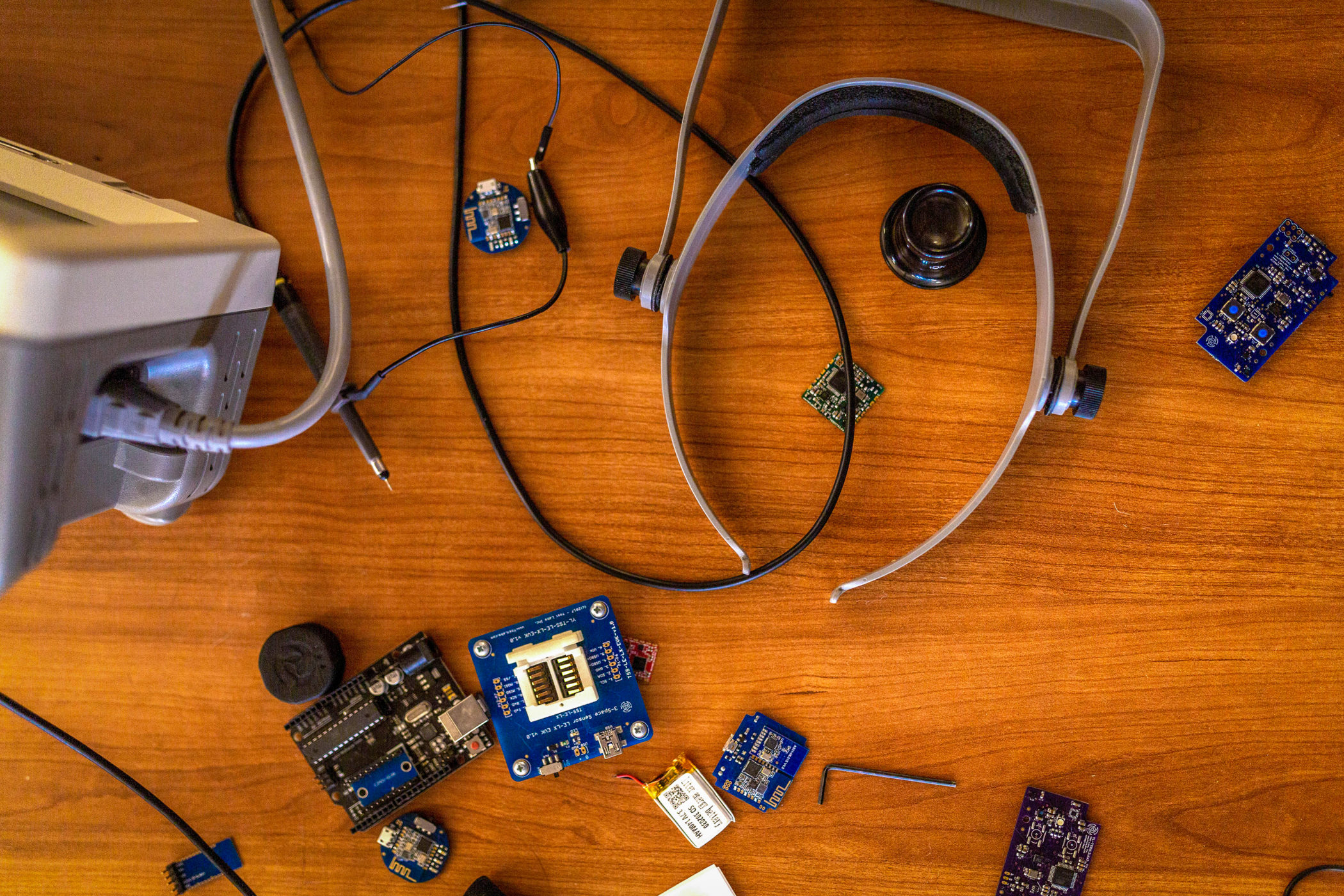

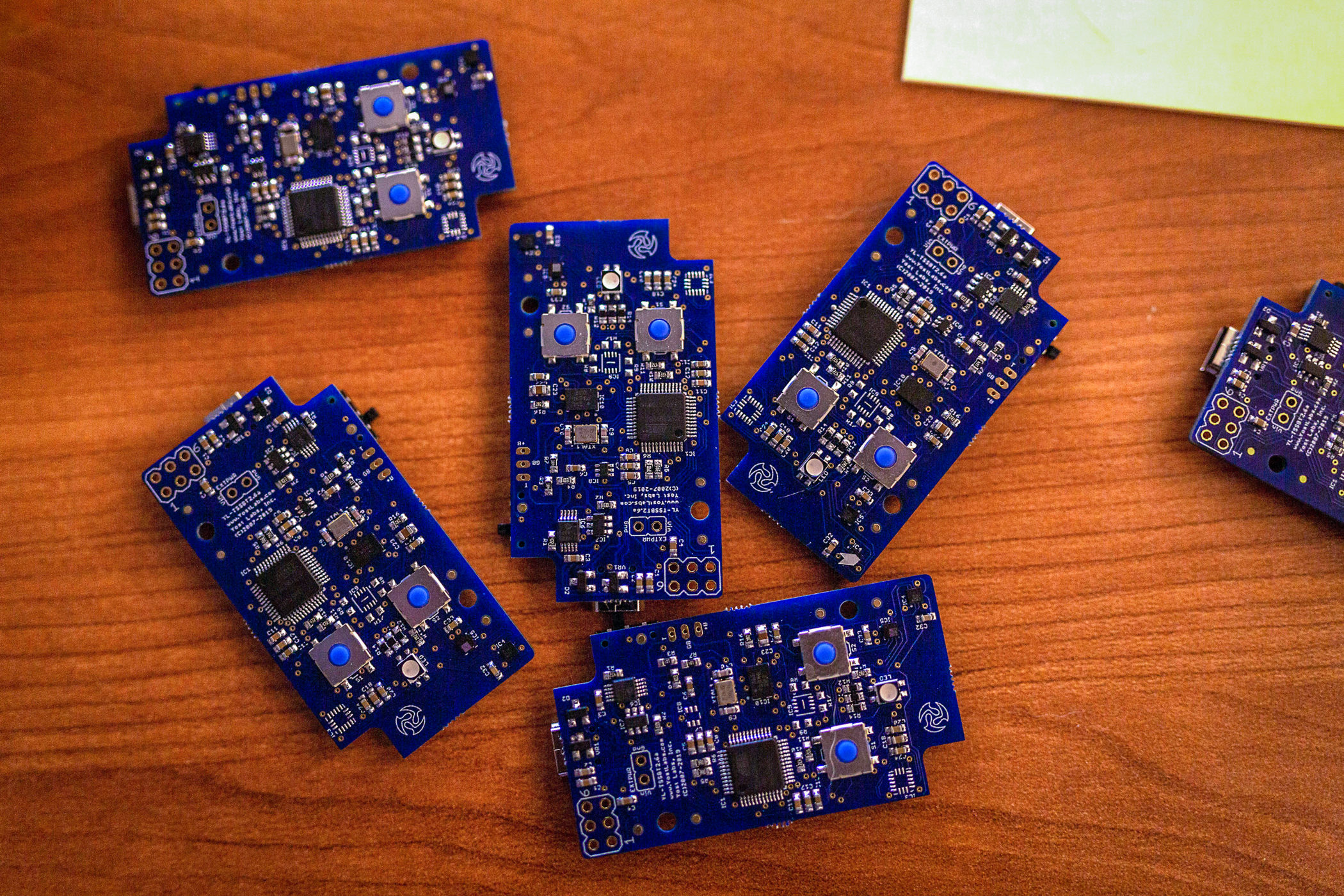

Founder, Yost Labs

Anyone looking for proof of the high-tech work that can — and already is — happening in rural America should spend time with Paul Yost’s story. An interest in computing and problem-solving fueled the degrees that landed Yost a position on the engineering faculty at Shawnee State University. But a passion for teaching didn’t satisfy all his intellectual interests, which was why Yost decided to engage his entrepreneurial side, first with Yost Engineering, then more recently with Yost Labs, a cutting-edge producer of motion-capture and inertial sensors for a variety of clients and applications — from tech leaders to the military, industrial contractors and entertainment companies. All without leaving downtown Portsmouth, where Yost and his family live in the loft above the Yost Lab facility and the former competitive table-tennis player can grab a game on the company’s table.

“The thing that I found dissatisfying in academia was that you would work on those kinds of complex projects and those kinds of problems, then maybe you get some sort of publication out of it, but it wouldn’t really do anything. It would sit on the shelf and you’d wait for somebody else to do something with it. And so, in 1999, there was some AI technology that I was working on — that was sort of just a fun project — but then I saw some opportunities to apply that to commercial settings, and so I started a company.”

“We’ve had clients that have come to talk to us about collaborative projects and working together and the first question they ask is, ‘Why are you doing this high-tech company in the historic district of downtown Portsmouth?” It’s in the middle of nowhere, two hours from the nearest airport that most people would have access to unless they have a private plane. But realistically, there are a number of advantages to us being where we are.

“I located here to teach at the university, and it has turned out to be beneficial for the company as well. Because of the university and the quality of students that, specifically, the gaming program gets, we have access to talent. And the other advantage that we have, I think, in a small place like this is that we spend a lot less money on overhead. The cost of living is low, the cost for our space that we have the business in is low. If we were to pick up this 10,000-square-foot space that we’re using for our business and try to move that into Silicon Valley, at the rent costs that are out there, we’d spend so much money on our overhead that we could spend less money on product development and talent and other areas that allow us to have a little bit of a competitive edge.”

It doesn’t end here.

Portsmouth is a great example of what can happen when America’s small towns embrace the hard work required to reimagine what is possible and begin creating digital economy ecosystems that can meet the future head-on.

Through its Rural Innovation Initiative, CORI’s work makes it possible for local leaders to connect and learn from each other in a community of practice. RII communities have a range of resources at their fingertips to help implement what CORI has identified as Direct Drivers of vibrant digital economy ecosystems:

- Access to Capital

- Scalable Tech Entrepreneur Support and Incubation

- Inclusive Tech Culture Building

- Access to Digital Jobs

- Digital Workforce Development and Support

Each of these elements allow communities like Portsmouth, Ada, Springfield and others to compete in the broader tech economy.

Learn more

To meet the Rural Innovation Network communities doing ecosystem building in small towns across the country, you can find a list here.

If you are a community interested in working with us to grow or build your own digital economy ecosystem, please contact us.

To learn more about our work in this space, be sure to check out our blog and sign up for our newsletter.