Portraits of a community: Platteville

The only thing driftless about Platteville is its location.

Set in southwest Wisconsin’s unique and picturesque Driftless Region, so named because glaciers never covered it in the last ice age, Platteville is a place of rolling hills, fertile fields, and stark river valleys that tumble toward the Mississippi River.

But it’s also a place of innovation and iteration.

Deposits of lead and zinc fueled early boom times as part of the mining industry. Agriculture flourished. And the area established an economic anchor in higher education at what is known today as the University of Wisconsin-Platteville. Previously a teacher’s college, then a mining school and a technology center, it’s an institution that, like its namesake town of 11,800, has continually transformed to meet the needs of the day. Most recently it has developed into a reservoir of engineering know-how across multiple sectors, just a few hours’ drive from Milwaukee and Chicago.

And in 2020, a Build to Scale Venture Challenge grant from the U.S. Economic Development Administration helped provide the resources to launch the IDEA Hub Accelerator, an initiative local leaders hope “stirs the entrepreneurial spirit of Southwest Wisconsin” through workshops, programming, and connection-building. With the IDEA Hub, Platteville has the chance to turn the innovation happening on campus and in the community into the foundation of a new, thriving tech-based economy.

That’s why the Center on Rural Innovation visited Platteville for the sixth piece in its “Portraits of a community” series. Previous installments featured Taos, New Mexico, Springfield, Vermont, Ada, Oklahoma, Portsmouth, Ohio, and Red Wing, Minnesota.

These stories are intended to shine a light on the people who make up the unique ecosystems within CORI’s Rural Innovation Network, which connects rural leaders and advocates around the country to accelerate their learning and amplify their work on the ground.

Marcia Harr Bailey

Founder, Prototype Your Life

Marcia Harr Bailey’s globe-trotting career in education didn’t just take her back to her native Wisconsin, it took her to the same campus where her parents met decades earlier. She taught in Thailand, performed her doctoral research in Laos, and is now a professor at UW-Platteville with degrees in business, management, and leadership. What’s more, she’s living the same material she teaches as she attempts to launch her own startup, Prototype Your Life, an entrepreneurship mindset curriculum that she’s digitizing via an app. Funded in part by an award from Wisconsin’s Ideadvance program, she participated in the IDEA Hub Accelerator’s first cohort in 2021, reaping the rewards of mentorship and honing her market product fit.

“I’ve taught this with over 1,500 students, and I’ve always incorporated a reflection component. I could see the tremendous takeaways that my students were having from what some would probably think are just silly comfort zone challenges. Once I realized that, I thought there was something to this. Seeing the students work on different challenges … by the third course, they really have that prototyping mindset ingrained and they like to take on new things, try new things. … I participated in the WiSys app search challenge, then I participated in the IDEA Hub summer accelerator, and after doing a lot of customer discovery I’m realizing that this is something that is valuable beyond undergraduate students — like, startup accelerator cohorts, the facilitators of these programs are very interested in this idea.”

“For me it’s really about impact. I want to be able to help more people realize their life’s ambitions through this process. … I love teaching business. And when I was living in Thailand, I decided OK, I want to go on and get a Ph.D., I want to be a professor, so I came back to the U.S. and I got my Ph.D. in education. I was really interested in higher ed, service learning, and connecting what’s happening in the classroom and having an impact in the communities for community partners.”

“I feel like I’m playing in the sandbox in some ways, and love that part of it. Also, I feel like I always want to push myself out of my comfort zone so that I’m modeling that for my students. And I feel like this is a great way for me to continue to do that and, ultimately, to make something that’s going to be really useful for students. … It’s one of those things where I could just keep continuing to do what I’m doing and it would be fine, but like I said, I really want to help make an impact. And if I want to make an impact, I need to make this digital.”

Seneida Biendarra

and Gokul Gopalakrishnan

Co-founders, Skillzboard

There just wasn’t a good way to teach certain technical skills to new climbers — that was the realization that drove four members of the University of Wisconsin-Platteville’s Outdoor Adventure Club to create Skillzboard in 2019. Seneida Biendarra was one of those student-entrepreneurs, an industrial engineering major initially drawn to Platteville by the school’s engineering focus and soon taken by the geography that makes it an outdoor playground. Along with their faculty advisor, Gokul Gopalakrishnan, a passionate and experienced climber, they began the 21st-century tech-based development process: producing and testing a digital 3D design, and finding a manufacturing partner to reproduce it. Their finished product, now available on the Skillzboard website, allows climbers to practice rope and anchor techniques just about anywhere — it won first place at the WiSys Innovation Showcase in 2019 and was a finalist in Moosejaw’s 2021 Outdoor Industry Accelerator.

Seneida: “In Platteville, you’re actually an hour from six different ice climbing locations — I can’t say that for the Midwest, in many cases. There’s a lot of outdoor rock climbing and biking, great road biking, some mountain biking. And then just paddling is beautiful out there, so there’s an outdoor adventure at every turn whether or not you’re looking for it.”

Gokul: “I think for us kind of the spark was COVID, actually. During the lockdowns, pretty much all or most of the climbing gyms in the country had been closed down. And not only that, but a lot of state parks and outdoor climbing locations were also closed off for a really long time. The climbing community was basically yearning for something to do that they could do at home, and so this is something that had been a little more than a theoretical exercise until that point, but that’s when we were like, ‘You know what, folks, the time is now.’ We need to move on this. There are thousands of climbers out there just itching to have something to do. … It’s kind of crazy that this doesn’t exist in the commercial space, so we should make it happen.”

Seneida: “I think, immediately, we knew how unique our product was in the climbing space because there’s a lot of tools for physical training and one of the biggest hurdles for people moving from a gym to outside is that there’s not a lot of tools for skills training — the ropes and the knots and all the systems which are very important.”

Seneida: “The hardest part was trying to find what was beyond our initial concept, which is kind of funny because we did a lot of kind of out there ideas and ended up paring it back. When we first did this pitch, it was with a plywood piece of wood with some bolts on it. We were trying to find different mounting mechanisms, we were just kind of looking at the user, and trying to figure out if a guide is going to use this, where are they going to use it? … That’s why we have a tree hugger that you can just put up on a tree. And then if you’re home you don’t have a lot of mounting options, especially if you’re renters, that’s how we came up with the idea of putting it over the door — then we did a lot of testing to make sure it didn’t damage the door. But you can hook into your harness and actually weight a door without damaging anything in your house.”

Gokul: “A bunch of this started off pen-and-paper, and doing some modeling to understand how you make a system that’s, A) easy to use but B) also strong and stable. Because when you come up on the real thing in the real world, it’s all fixed in place, and it’s completely immovable, and you’ll want to have a system that’s both portable and lightweight, and easy to carry around and set up, but also something that’s not going to swing or move around a lot when you weight it. And if you weight it in a non-symmetric manner, then you want it to stay stable, right? So there was a fair bit of doing a bunch of math and physics calculations, and then doing some modeling, figuring out dimensions, positions of where the different forces get applied. Then we started making prototypes, just on campus, using plywood. … I think we’re at a pretty solid place now where we’re very comfortable with how everything feels, handles; stability, strength. We went through at least six or seven different versions of these boards before we sort of finally settled on something that’s close to where we are now.”

Gokul: “I have no background in business or entrepreneurship. My bread and butter is doing science and engineering, and so it was definitely a huge learning process for me as well. The easy bit is sort of figuring out how to make these things. All of the other stuff from questions about liability to making websites — which Seneida is our guru on that front — to pricing to marketing to setting up taxes. All of these things, it’s all been definitely a new process and learning process and interesting to know and to do it with this gang.”

Antonette Cummings

Founder, CREMSHEL and CAML-R

A documentary about homelessness in the U.S. sparked an “aha!” moment for Antonette Cummings, a native Texan and former engineer at Bell Helicopter turned professor at the University of Wisconsin-Platteville, that has rippled outward to produce not one but two innovative startup concepts. The first, CREMSHEL, was a design for a temporary emergency shelter that could be made out of recycled plastics. That informed a second idea inspired by the very ground beneath Platteville: A remote-operated vehicle that can line old mines with plastic so they can be filled with coal ash. It’s a project that could solve issues of mine subsidence in Platteville, a former lead-mining community, dispose of millions of tons of coal ash, and reduce greenhouse gases — and something that Cummings thinks could have even more potential beyond those applications.

“Platteville is a mining community and you can only build buildings so tall here because we don’t know where all the mine shafts are — they can collapse, and that’s a problem called mine subsidence. … And then it occurred to me to pivot my business, and now we’re CAML-R — a coal ash mine liner, remote-operated vehicle. The idea is that it will go into an abandoned mineshaft line it with plastic to make a nice barrier, and then fill it with coal ash which can be considered toxic, because it does contain heavy metals, and plastic is an excellent barrier for heavy metals. It’s just refilling the Earth with the stuff that we took out of it. Yeah, only, only put it in a plastic lining so that any of the toxic stuff is more of a trickle, and not a flood. That’s where we are now, and that started from watching a documentary on homelessness in the U.S.”

“The short story is I want to get this intellectual baby born and I want to have ExxonMobil adopt it — and that is not even a little bit of an exaggeration. Just in April of this year ExxonMobil’s CEO wrote a story about sequestering all the carbon dioxide generated in the last 130 years under the Gulf of Mexico after they finished oil drilling. But you need the technology, you need the legislation, you need the public and private funding. It’s this huge, huge project, but it’s not a Band-Aid, it’s now a permanent solution. … And so this would provide another solution that actually solves multiple problems in one go. That’s my goal.”

“I’m sure people or people like me often talk about how doing a different type of work is rest, right? It’s not possible for me to sit and do nothing. … Our timeline is tight. My partner and I, he’s working on a first iteration of the plastic, I’m working on a first iteration on the robot for tabletop. We’ll get some federal budget money to scale it up, and then go for the IP protection, and then license it. So this is not more than a five-year project, tops.”

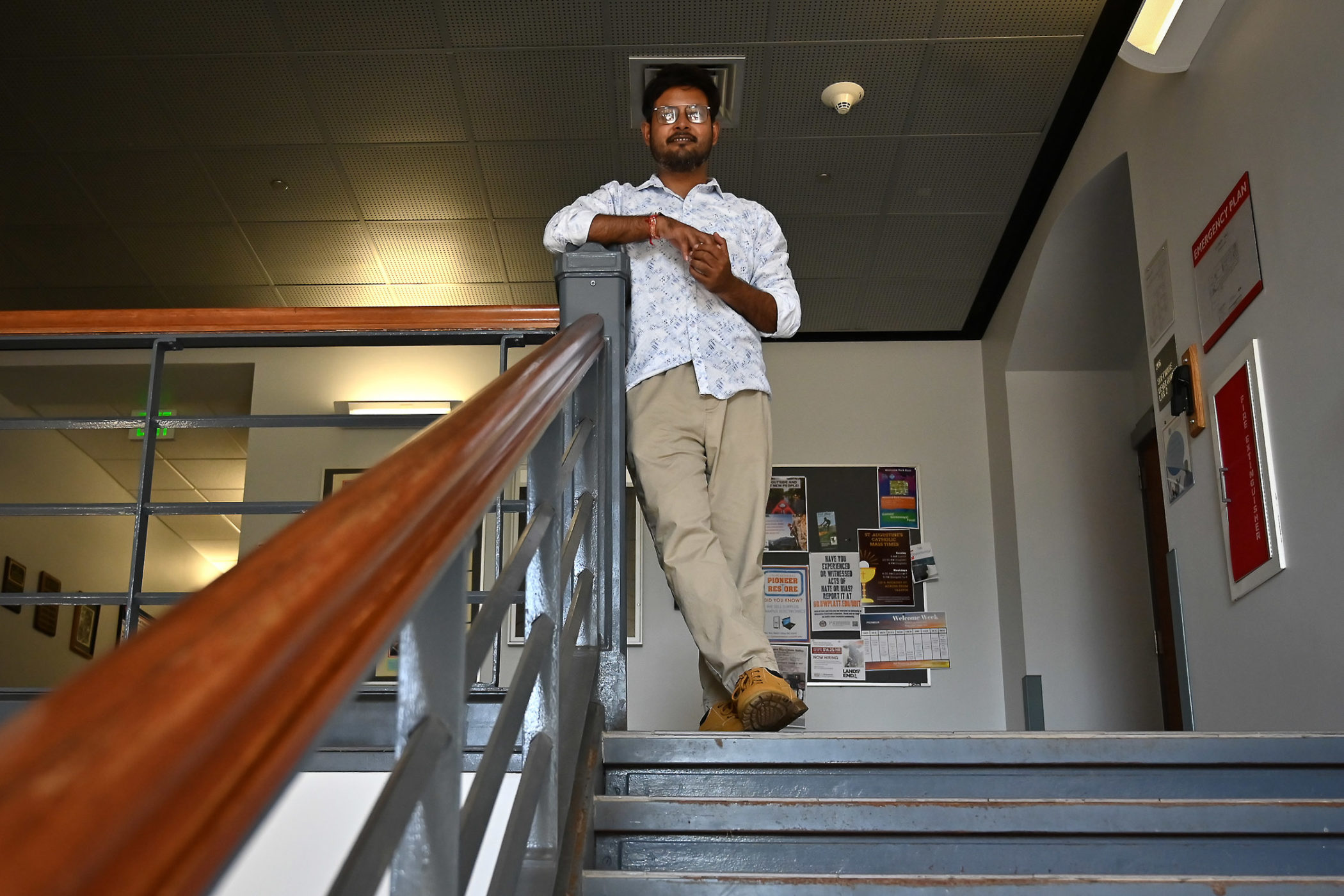

Arghya Das

Founder, Onstitute

Arghya Das came to the University of Wisconsin-Platteville in 2018 after earning his Ph.D. in computer science at Louisiana State. A former software developer, he wanted to teach and had found his place — albeit in the smallest town he’s ever called home. And when the arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic pushed more education offerings online than ever before, Das began exploring what a data science curriculum could look like in that context. Between contacts at IBM from his research days and the entrepreneurial support of the University of Wisconsin System (WiSys), Das developed a platform called Onstitute that can serve as a venue for lectures and material, as well as a low-cost way for students to access supercomputing infrastructure regardless of their location — something Das hopes can revolutionize access within the discipline.

“What’s great about this is it’s not only just an educational platform, where you can see the video lectures and all these things. But you will get everything — IBM is actually supporting me with all their infrastructure, so if you want to get access to some high-quality supercomputing infrastructure, you will get that in the website. Also, we provide all the virtual machines, Docker containers, and all the different types of technologies that are required to make your machine a development system, instantly. All those services we are providing through the website. It’s kind of a one stop solution for everything, whatever you need for data science learning.”

“And, of course, this is online, so regardless of location, you can do anything. For example, some company has acquired some kind of supercomputing infrastructure back in India, and a student from UW-Platteville can access it, or the other way. Also, let’s say UW-Platteville got some funding and got some infrastructure, and then a student from India can access it. I hope at some point of time, it will act as a good collaborative platform between different types of different industries, universities and industries.”

“If you asked me about the long-term goal, I want to see Onstitute as one of the world’s bigger education franchises. We have scientifically proven teaching techniques for data science, we have some collaboration with Facebook research, IBM, Amazon and all the different companies from which, after discussing all these things, we have developed some teaching strategies, fundamental techniques for data science learning. So I believe that if we can develop it properly, then anyone will be able to teach data science to anyone. That’s why I think at some point in time, I want to see it as a big education franchise where we will recruit the instructors, so teachers will come and they will just register with us to teach our syllabus in our way. We will just give them the teaching recipe instead of the food recipe, and they will just follow it and we’ll teach everyone.”

Missy Emler

Owner/Chief Learning Officer, Modern Learners

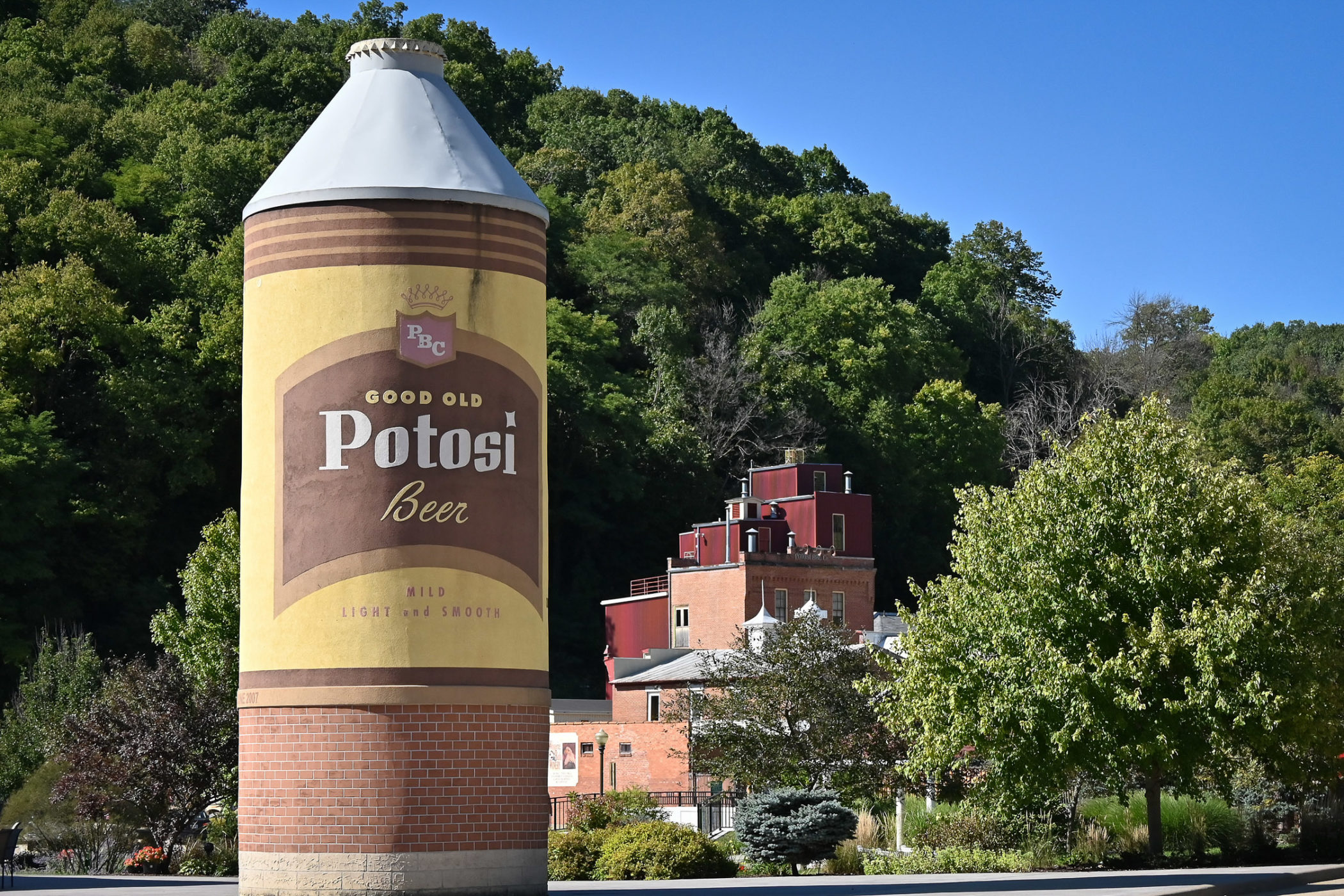

The internet — and the COVID-19 pandemic — gave Missy Emler the opportunity to turn her online platform into something greater and she did just that. A former classroom teacher and principal, Emler’s day job is as a regional director of innovation for the state’s Cooperative Educational Service Agency, working with 31 districts in the corner of Wisconsin where she grew up. And, sure, like any rural area it has its limitations. But from her family’s home in Potosi, a small town just west of Platteville on the Mississippi River, she’s been able to grow her side project, Modern Learners, an online community for school leaders, into a service that also facilitates online and hybrid events for groups across the country and the globe. When she’s not busy with that and her day job, the area’s wealth of outdoor activities offer more than enough for her to enjoy with her husband and sons.

“I grew up in a farming family, both sides of my family are farmers in the area, and when you grow up on a farm, I just don’t know that you can leave it that easily, even if you don’t continue to work on it. It’s just part of who you are that’s not something to leave behind really easily. … I feel really compelled to serve the people, and specifically like the kids, because I’m an educator, a lifelong educator, I just feel compelled to serve the region, and sort of feel like my skills and talents and gifts are somewhat different or out of the ordinary for people here. And so I feel a real need to serve the people and I’m a futurist, I’m an innovator, I’m constantly looking for a new way to do things, and I love sharing that opportunity with people in the region.”

“Modern Learners was putting the focus back on learning. And now the vehicle to do that is events, and it wraps around into community. We’re building a community of event hosts, people who are having events … we’re connecting people so that they can share their experiences and then we are just building out events and creating really rich online experiences that are now also shifting to a hybrid model.”

“One of the barriers for me in my learning journey throughout my life has been that I can’t always get to the national conferences with the best speakers or the best lineups, and I’m very locked into what I can access regionally for learning. And because I’ve been able to connect online for so long, and through so many different mediums online, I have been able to connect and bring world-renowned speakers to our region and to other people’s small regions. … Not everyone understands how being connected actually can bring a strong support system to our local region, so I can take what I’ve learned from these other people in these other places, and apply the best things that I see to our own context. And that’s really exciting — but being virtual is what allows that to happen. Geographically, I’m sort of stuck. But the internet can take me anywhere. And it’s really exciting. Yeah, I love the internet.”

Michael Herrera

Community Manager/Game Designer, Clopas Games

A degree in environmental science followed by a job at a native plant nursery saw Michael Herrera criss-cross the country from his native California to northernmost Maine and back to Catalina Island. Herrera wound up in the middle, in Platteville, after switching careers to video game design and getting recruited by the original founder of Clopas Games, Scott Adams. Now the CFO, and part of a trio that’s taking over ownership from Adams, Herrera is trying to grow the Christian-oriented game studio with a new model toward sustainability as part of the IDEA Hub’s first accelerator cohort. The studio has a relationship with the local college, UW-Platteville, helping students with senior design projects, and its team of about a dozen is balancing the demands of dual revenue streams: gaming and creative design services.

“I really liked the idea of being able to design something that people could interact with, I think that there is something about play — play that allows you to use your imagination, and to interact, as opposed to just being passive, like, you know, TV, you just sit there and watch. I enjoy the idea of interacting with the player, even though it’s not an immediate interaction, like trying to anticipate, ‘Well, how will the player feel if we do this? Or if we do that?’ And then kind of giving them the chance to kind of discover and enjoy and really give different insight, just through the way that they play.

“I’ve a really good relationship with my (colleagues), David and April. I’m the older of the group — I’m in my 50s… and so I’m kind of helping them get a leg up so that, we’re hoping, the studio continues on ad infinitum, so we can pass it on to the next generation, and then the next generation. We’d really love to see digital infrastructure emerge here in Platteville. I think that’s why we’re working with the university. We want to see students get their grounding in game design and game development, and be able to work for us or other companies. And you’ll really be able to kind of plant something here in Platteville.”

“One of the challenges innate in just making video games is financial sustainability. It’s really feast or famine, like you make a game and you spend a lot of money, put it out into the world, hoping that it brings you back money. And then you’ve got to start over again. And so you got money rolling in, but then it tapers off and now you’ve got to start over again. … And that’s why we ended up doing the creative design services that we do. We have a wonderful partnership with GoLocal Media. Because of what their needs are, we’re able to get a sustainable source of income, source of revenue. It’d be really hard for us to do that without them. The three of us are struggling to find a way to a methodology for others to follow. Like, how do you create an indie game studio in a rural area, without having to become beholden to a publisher? That’s been an interesting journey in itself.”

Stacy Jax

Founder, Trinity Sound Technologies

A mother and teacher, Stacy Jax began her startup journey in the wake of the Sandy Hook school shooting in 2012. The continued presence of such tragedies in the headlines left Jax wondering what technology could do to help. Her creation, Trinity Sound Technologies, is a patented gunshot detection system that uses specialized sensors and can send instant notifications via email or phone with the precise location of an active shooter in a school. But as she honed her product, which is now manufactured in rural Wisconsin, she realized the bulk of the advice she received — from people with established businesses — wasn’t always applicable to startups like hers. Through the IDEA Hub, though, Jax found the entrepreneurial support she wasn’t getting in larger ecosystems closer to her home in Baraboo, another small town in the region, about 80 minutes north of Platteville.

“I started thinking about emergency procedures I used as a teacher in my classroom, and the idea of a fire alarm came to mind. Why isn’t there a piece of technology installed, just like a fire alarm, throughout your whole building that can hear the sound of a gunshot? … It took me a lot, not having a technical background, to find the right programmers who could create a solution that would work and provided the immediate notification that I felt people deserve. What’s been really fantastic about the company that we partnered with was they created a solution like no others in the market. We have a U.S. patent on it, and it’s not a listening device. In areas that have acoustic sensors, recording conversations is usually illegal, so ours is the only gunshot detection in the market that does not record conversations.”

“I’m heading this mission on my own. And being committed to driving the solution to the people who deserve this has been really hard … just surrounding me with like-minded people has been one of the greatest things I’ve gotten out of (the IDEA Hub) because it’s a lonely venture. It’s scary. But to be supported by all these other people who have been successful in doing it just helped me keep on the grind.”

“I’m in Sauk County … which aligned me with the Madison startup industry, and Madison has a really robust startup industry. I’ve gotten a lot of help from mentors there and other entrepreneurs. But what the IDEA Hub offers is different because you are not only getting guidance from experienced business coaches, but you are (also) exposed to other entrepreneurs who are in it, doing it, and maybe just have had a successful business launch, so they’re very fresh in their minds of what entrepreneurship is about. So I got theory and strategy from the Madison area, but with the IDEA Hub I really felt like being surrounded by other entrepreneurs was exactly what I needed at that time.”

Chris Wilson

Business Manager, Wilson Organic Farms

What the Wilsons are doing on the land they’ve tended since the mid-1800s isn’t new — it’s how they’re doing it on their 3,000-acre spread that is where the innovation starts. And a big reason why is Chris Wilson. After completing his economics degree at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Wilson returned to the small town where his family has farmed for seven generations, but did so as a risk manager and financial analyst for a firm in nearby Illinois. The father of two didn’t want the full-time farmer’s life — he saw that toil and stress growing up — but realized about five years ago that his professional skill set might help the family business reach the next generation. Partnering with UW-Platteville and its Dairy Innovation Hub, Wilson Organic Farms are exploring new technologies and grazing approaches that can modernize the operation, and potentially benefit the planet too.

“Fundamentally, my main draw is that we are an organic farm, and I would be the seventh generation on that farm. The initial pull into that for me was making sure that we had a chance to have an eighth generation on the farm. … I think in 2015-16, because I’m involved pretty deeply in the industry, I could see it was going to be a pretty rough stretch (for farmers). And I just wanted to make sure that we, as a family farm, were prepared for that. What drives my interest is just trying to find a different way of farming that solves the challenges that we have in the 21st century. I’m deeply concerned about climate change — I’m deeply concerned that the current approach to farming is furthering climate change in different ways.”

“We’re trying to figure out a way in which we can use either robots or drones or sensors in signaling to move those cattle in an automated system. And then, eventually, the idea would be to pair that with satellite data, and maybe on-the-ground sensors that would tell us exactly — based on forecasts, and prior information and knowledge of how pastures grow — how to come up with a precise plan for managing those pastures in a way that optimizes for everything.”

“Right now, it’s pretty tough to be a smaller-size farm and make it in agriculture. … A lot of times they don’t have the necessary background or training to excel at (grazing), but many times it also comes down to just resources, they don’t have the financial and capital resources. So if we can bridge that gap through technology, and there’s the opportunity to maybe put — instead of hundreds of acres — thousands or millions of acres back into a system that is putting carbon in the ground and filtering the water and capturing rainwater and things that benefit everybody.”

It doesn’t end here.

Platteville is a great example of what can happen when America’s small towns embrace the hard work required to reimagine what is possible and begin creating digital economy ecosystems that can meet the future head-on.

Through its Rural Innovation Initiative, CORI’s work makes it possible for local leaders to connect and learn from each other in a community of practice. RII communities have a range of resources at their fingertips to help implement what CORI has identified as Direct Drivers of vibrant digital economy ecosystems:

- Access to Capital

- Scalable Tech Entrepreneur Support and Incubation

- Inclusive Tech Culture Building

- Access to Digital Jobs

- Digital Workforce Development and Support

Each of these elements allow rural communities like Platteville, Red Wing, and others to compete in the broader tech economy.

Learn more

To meet the Rural Innovation Network communities doing ecosystem building in small towns across the country, you can find a list here.

If you are a community interested in working with us to grow or build your own digital economy ecosystem, please contact us.

To learn more about our work in this space, be sure to check out our blog and sign up for our newsletter.