Understanding broadband resilience and natural disaster risk

Resilience can vary widely based on the specific disaster risk that each region faces, as well as the strength or resilience of the region’s current telecom equipment.

The increasing frequency and severity of climate-related disasters — and the raw destructive power of natural disasters like hurricanes, earthquakes, and tornadoes — pose a serious threat to the broadband infrastructure we rely on each day.

Every disaster underscores the value of having broadband systems that are resilient — they can withstand damage and minimize the likelihood of potentially dangerous service outages. Typically, a resilient system requires:

- Route diversity: The availability of multiple paths without common points.

- Redundancy: The provision of duplicate assets to provide back-up.

- Protective measures: The additional processes and systems used to reduce the likelihood that a system will be affected by natural disaster.

- Restorative measures: The additional processes and systems used to reduce the time needed to return a system to full functionality.

While it is preferable to incorporate resilience in the initial design stage, resilience can also be incorporated in the maintenance stage by retrofitting existing infrastructure or in emergency planning for network failures. (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, 2018).

How do regions compare from a resiliency standpoint?

Not all regions face the same broadband resiliency challenges.

Resilience can vary widely based on the specific disaster risk that each region faces, as well as the strength or resilience of the region’s current telecom equipment. An evaluation of a region’s specific broadband resilience against relevant disasters can help vulnerable regions more effectively prepare themselves against adverse weather events.

In order to show regional differences, we conducted an analysis using the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s expected annual building losses (EABL) calculation to represent relative risk profiles, where the higher the building loss value, the higher the risk for climate disaster. To assemble the risk profile ratings, we apply the methods used by FEMA to calculate relative risk profiles for all census blocks that had a risk of disaster greater than zero.

Our Aug. 31 webinar will dig deeper into our methodology and findings.

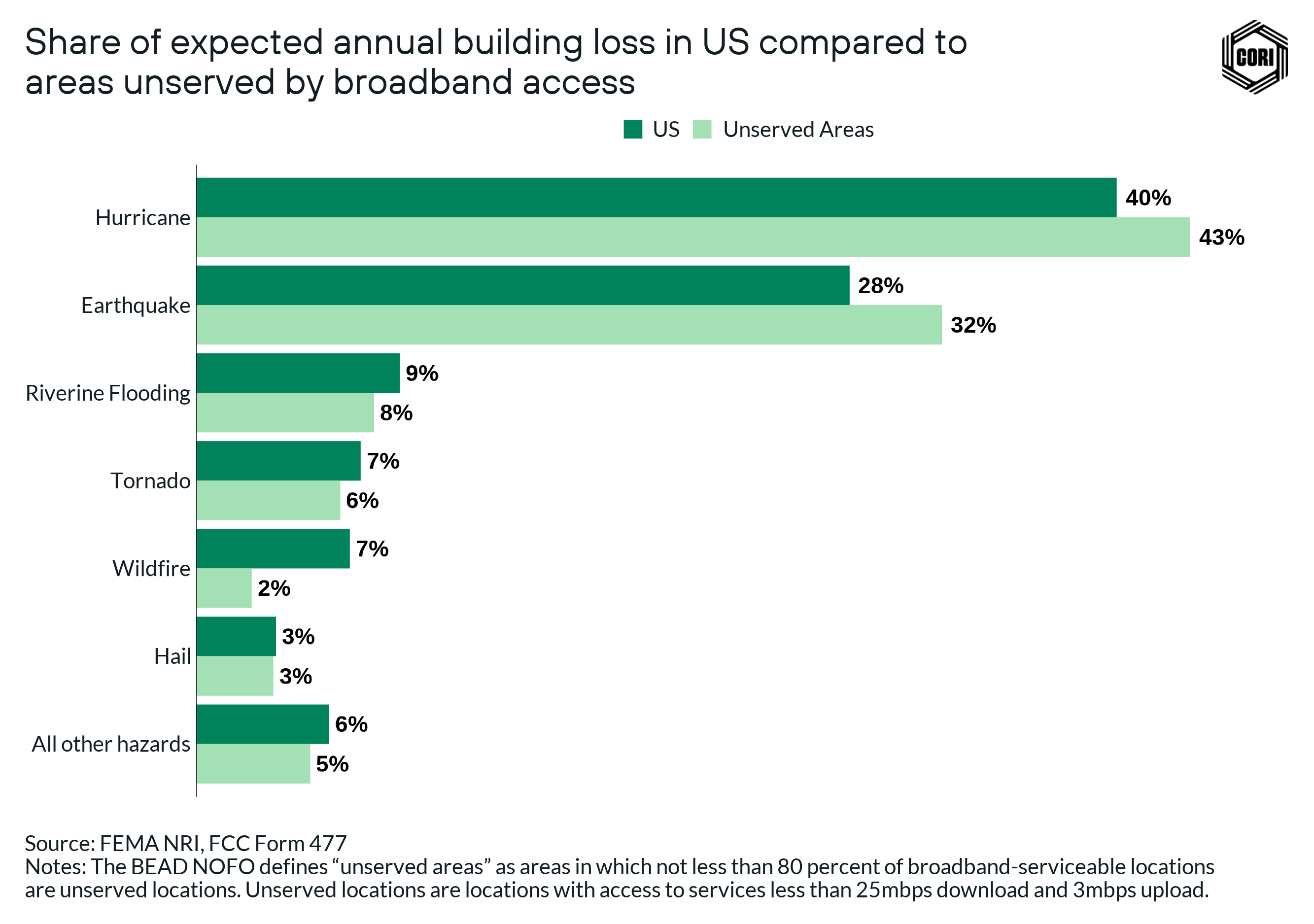

We assessed vulnerabilities in unserved census blocks at a statewide and regional level to understand the prevalence of potential risk and found that hurricanes and earthquakes cause the most destruction across the U.S., accounting for about 68% of all expected annual building losses. These are followed by riverine flooding, tornadoes, and wildfires, which together account for about 23% of all losses.

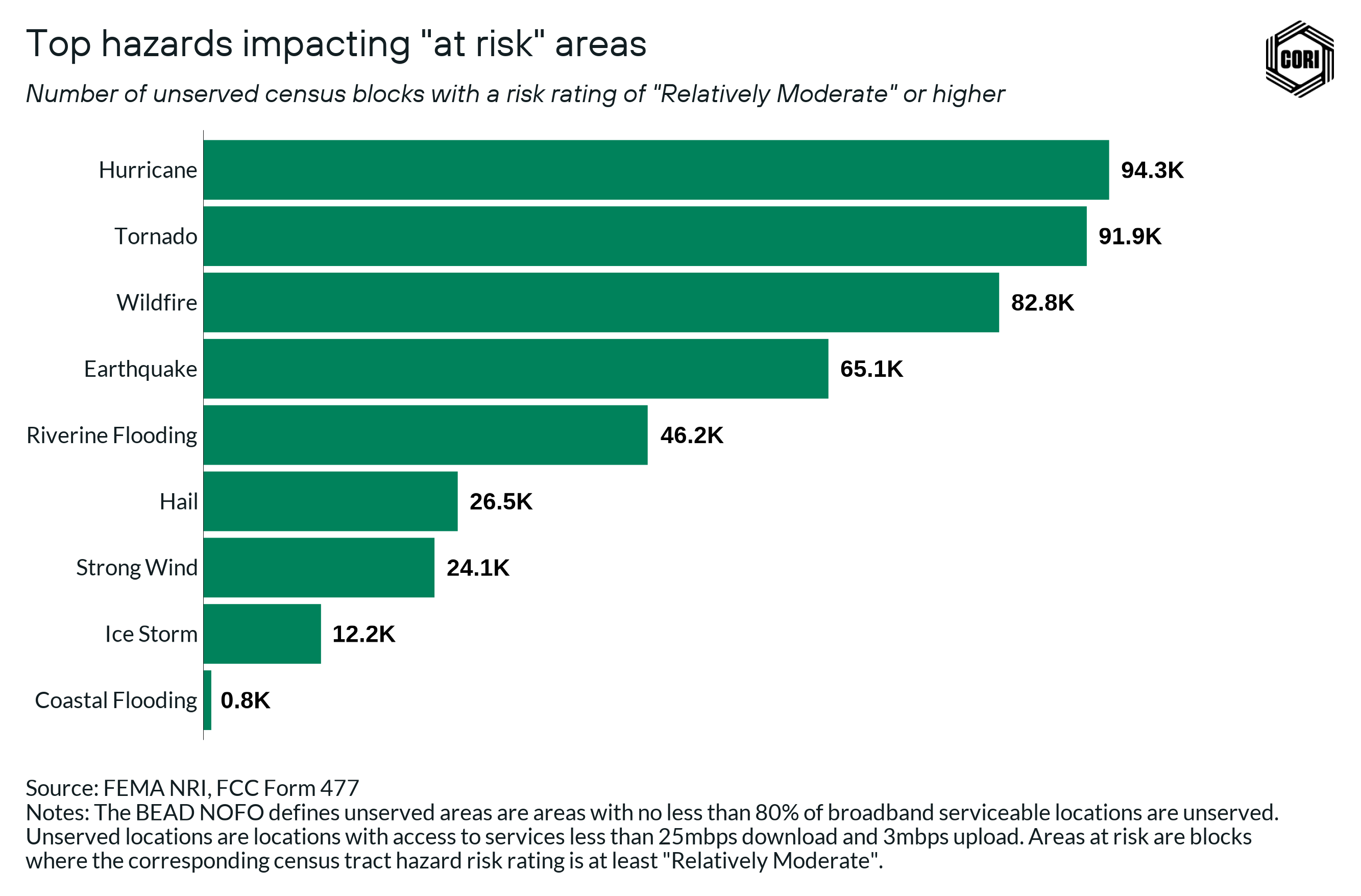

In the analysis below, we used areas that are likely to be broadband investment priorities and experience above average climate risk to identify the top hazards that are likely to be of chief concern when building out local broadband infrastructure.

We still see that hurricanes remain the top concern even at the local level. Using this analysis, wildfires emerge as a significant concern caused by the significant impact on rural areas in the western U.S.

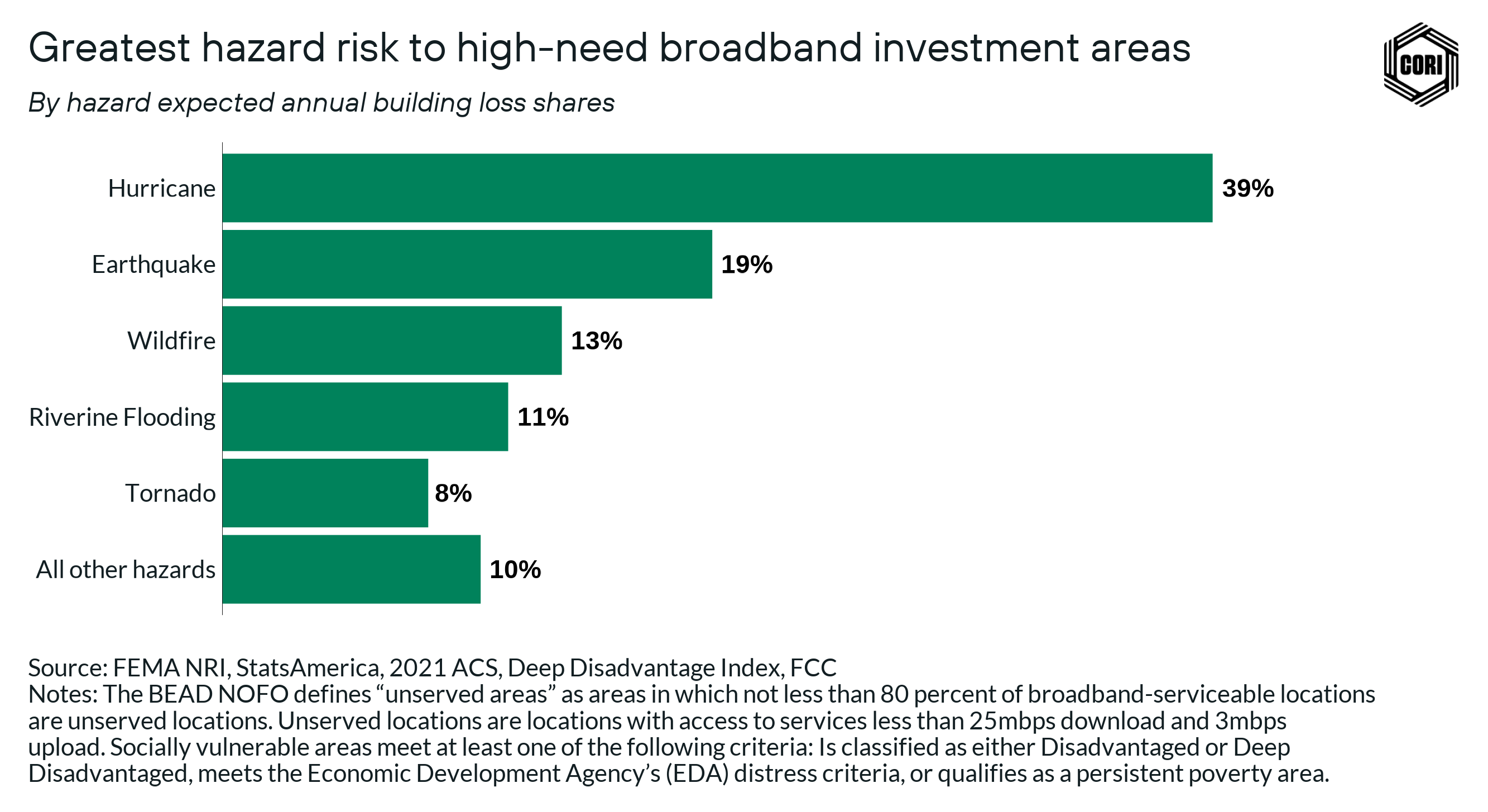

To better understand the intersection between climate risk, broadband investment areas (census blocks that are defined as unserved or underserved in the BEAD NOFO), and social vulnerability and community capacity, we identify areas that are disproportionately impacted by poverty, unemployment, and low per capita income. The private ISP market is less likely to invest resources in these areas, ultimately leaving these areas out of infrastructure development plans. BEAD investment in these areas is vital to eliminating the existing infrastructure gaps.

To identify these areas of high need that are more likely to require outside investment, we use the Index of Deep Disadvantage (isolating counties that are classified as either Disadvantaged or Most Disadvantaged), the Economic Development Agency’s (EDA) distress criteria, and the U.S. Census Bureau’s data on persistent poverty counties. If unserved areas meet any of these criteria, we’ve categorized them as socially vulnerable.

The most vulnerable populations that lack key broadband infrastructure are found in hurricane-prone areas, however, vulnerable populations without broadband are found across the U.S. to one degree or another. These populations are where BEAD funding is most needed to develop resilient broadband infrastructure.

These socially vulnerable populations face overlapping challenges in getting connected. This includes a lack of access to devices, affordable connections, and a heightened risk to housing and personal safety. Combined, it is even more critical that these regions have resilient broadband infrastructures to reduce the risk of communication systems and public safety functions failing.

State broadband offices can use the Broadband Climate Risk Mitigation Tool and accompanying report to analyze the specific contexts of broadband deployment proposals to ensure these deployments mitigate disaster risk. Local government officials can use the tool to have informed conversations with potential ISP partners deploying broadband infrastructure in their jurisdictions. And BEAD applicants can use the tool to understand census block level vulnerabilities in planned broadband deployments.

Be sure to explore each of these resources to better understand how to assess climate risks that could jeopardize broadband infrastructure deployment in areas that need it the most.

This post was made possible by support from Connect Humanity.

Stay connected

At the Center on Rural Innovation, we are working with rural communities across the country to help position them to thrive in the 21st-century tech economy.

To learn more about our work in this space, be sure to sign up for our newsletter.

Have more questions about broadband? Reach out to our team at broadband@ruralinnovation.us.