Bridging the gap: Empowering rural America through tech and innovation

By investing in the right infrastructure, training programs, and support for local startups, rural areas are becoming vital contributors to the knowledge economy.

It’s a myth that rural places can’t be centers of innovation. By investing in the right infrastructure, training programs, and support for local startups, rural areas are becoming vital contributors to the knowledge economy.

In our last blog, we discussed the important role that the knowledge economy can and should play in closing the gap between rural and nonrural places. The third story in our Rural Aperture Project, a multi-story series funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation’s Thrive Rural initiative, reviewed the essential ingredients needed for rural tech economies to thrive — broadband infrastructure, tech workforce development and support, and access to capital.

Now we’ll explore how leveling the playing field can benefit rural America in the present day and into the future.

Breaking down the barriers holding rural communities back

Knowledge economies require certain inputs to grow and thrive, such as a physical broadband infrastructure, a skilled workforce, capital networks, and more. Rural and nonrural communities don’t have the same access to these resources, an inequity that limits rural communities’ ability to participate in the knowledge economy.

By developing new tradable services and products, knowledge economies are important engines for economic stability that bring money into a community. We focus on three key ingredients for successful knowledge hubs:

- Broadband as critical infrastructure

- Human capital in the form of specialized education and training

- Financial capital in the form of investment in startups.

Broadband infrastructure

Prior to the significant funding allocations during the COVID-19 pandemic, federal policies left a considerable portion of rural residents without sufficient — or any — access to broadband connectivity.

Broadband access is associated with myriad economic benefits including increases in per capita GDP, higher rates of business formation, and higher property values for homeowners. The absence of federal broadband investments meant that rural areas consistently missed out on this key economic driver as well as social advantages that reliable broadband access brings.

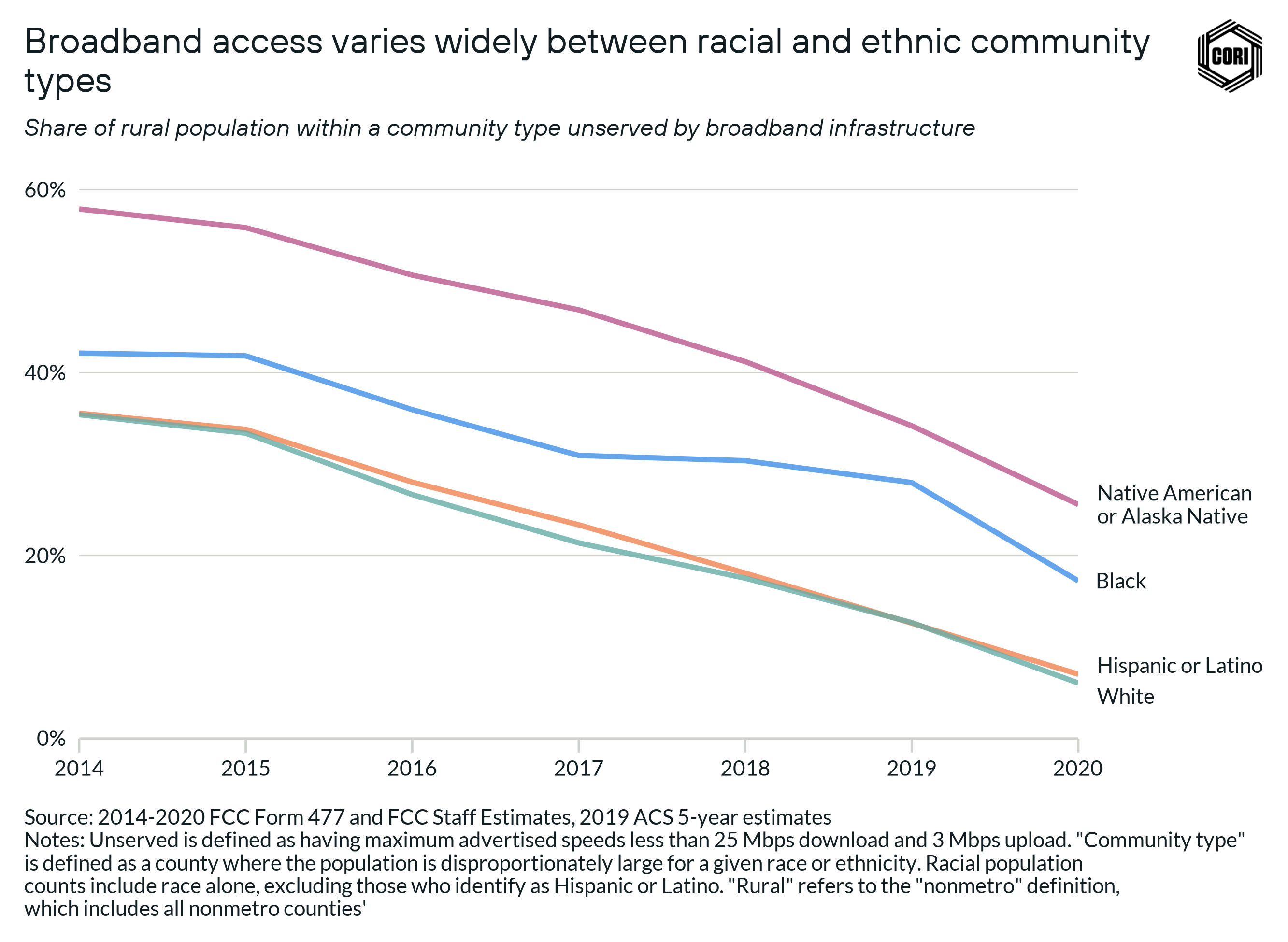

Broadband access, which the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) describes as having at least 25 Mbps download and 3 Mbps upload speeds, is much more common in nonrural areas than in rural ones. Since 2014, over 94% of nonrural areas have had this kind of internet access. However, in rural areas, only 65% had access in 2014, and it took until 2020 to reach 92%. (FCC Form 477 & FCC staff estimates).

The share of rural residents unserved by broadband access has dropped significantly in recent years. Still, minority residents in rural areas are more likely to be unserved or underserved when it comes to broadband. And for others, broadband remains inaccessible due to either lack of infrastructure or prohibitive costs.

We continue to see creative solutions to rural broadband connectivity such as going through electric co-ops or Vermont forming Communications Union Districts. These creative solutions have helped bring broadband into homes and businesses in many rural areas.

For example, the Maple Broadband Communication Union District built fiber infrastructure, and is paying an experienced operator on a per-customer basis to provide service at rates the CUD determines. Their partnership structure ensures every on-grid location in the community is served, rates are kept affordable for the long-term, and it creates a predictable financial arrangement with incentives aligned for all parties.

Despite these creative solutions and significant federal broadband investments narrowing the infrastructure gap between rural and nonrural areas, nonrural communities and economies surged ahead in knowledge economy growth and various tech employment opportunities during the intervening years. In order for rural knowledge economies to catch up, they will also need investments in workforce training and in their tech startups.

Tech workforce development

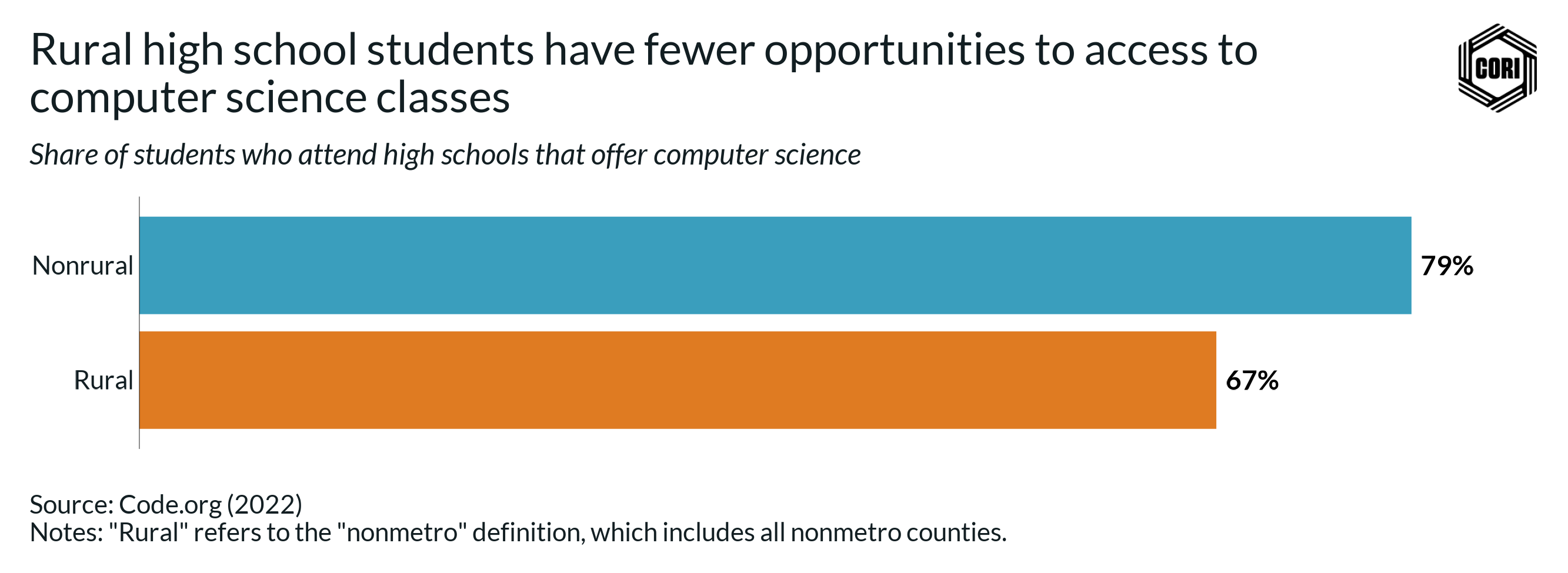

As the knowledge economy plays a crucial role in driving our country’s economic growth, the skills and knowledge of our workforce have never been more important. This emphasizes the critical need for training and education as key factors in economic development. Yet, rural high school students have fewer opportunities to access computer science classes and workforce training for tech jobs.

Historically, many tech roles required traditional four-year degrees, limiting access for many rural residents. However, the landscape is evolving. The tech industry’s acceptance of a growing array of alternative skilling pathways has rendered these jobs now more accessible to nontraditional learners, allowing a broader range of people to participate and thrive in tech jobs.

Alternative educational routes, such as associate degrees, tech boot camps, and certification courses, are now viable pathways, offering opportunities without the burden of extended educational commitments or hefty student loans. It is often the cost or time commitment of training that holds rural learners back from gaining new tech skills and benefitting from the trends in tech jobs.

Computer and math jobs are among the fastest-growing occupations in the U.S., with a projected increase of 15.5% between 2021 to 2031 — almost three times the overall employment growth rate of 5.3% in the same period (BLS). They are also some of the highest-paying jobs. Rural workers in these occupations earned an average of $78,843 in 2022, compared to the average rural salary of $48,536.

In Emporia, Kansas, a young mom named Jordan Davis turned an entry-level job with a local telecom company into a springboard to something greater — a stable, good-paying career that could support her growing family. Davis got a degree from the local technical college in her spare time, building a skill set that could get her to where she is now: Leading information security efforts for Emporia State University.

Jordan Davis

By tapping into the talents and unique perspectives of rural populations, there’s a significant opportunity to enrich the workforce in meaningful ways. Rural communities offer a diverse array of experiences and viewpoints that can be critical in driving innovation. This diversity of thought can lead to more creative problem-solving and novel ideas, enhancing the quality of work and output across various industries including the tech industry.

To create real wealth and staying power for these tech jobs in rural communities, we need to also translate these new talent pools into opportunities for tech startups that attract investment.

Venture capital investment in rural tech startups

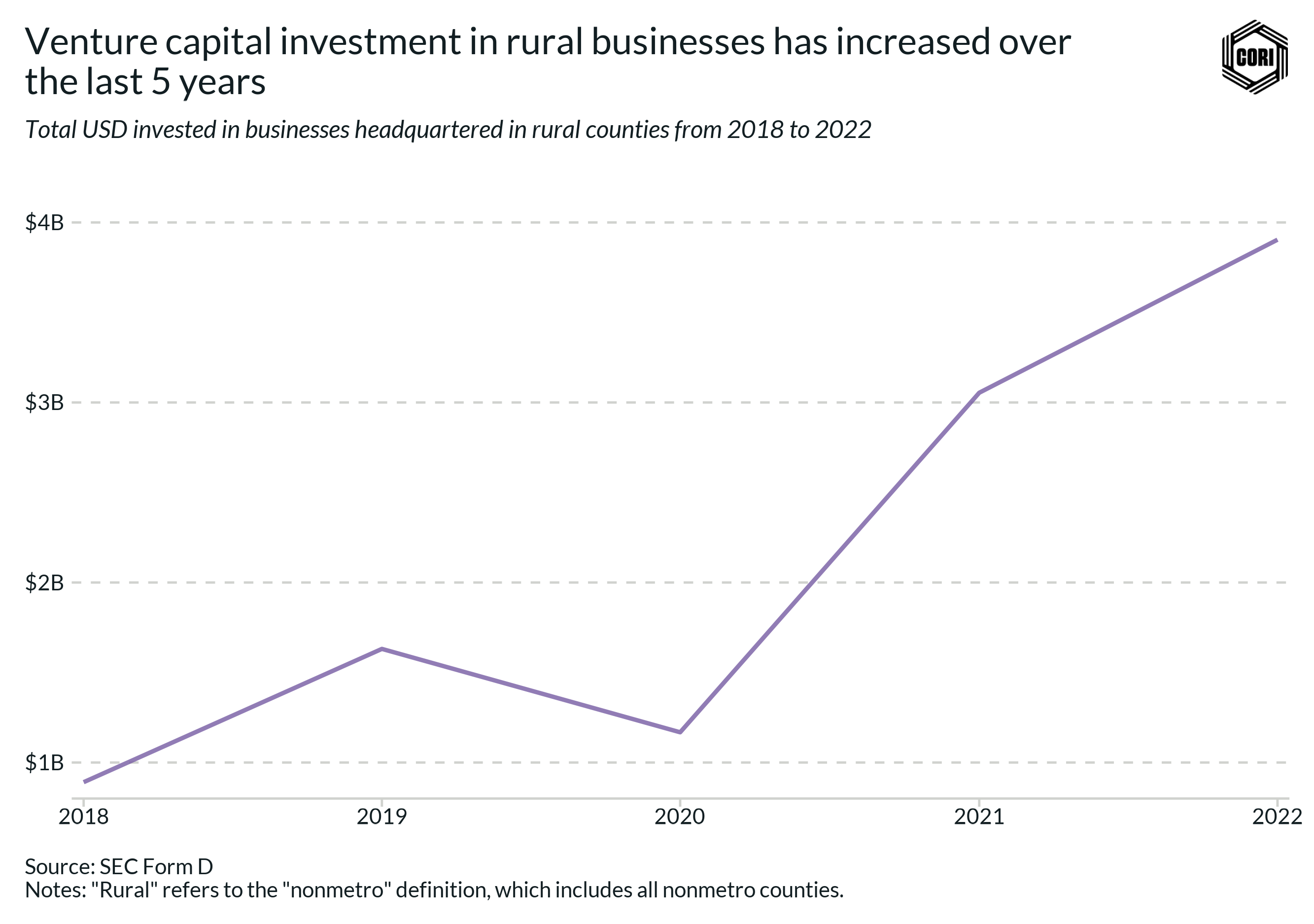

Venture capital firms have traditionally invested in very limited geographies — those closest to their offices — and they are more likely to invest in areas where they have strong social networks.

Indeed, metropolitan areas received 99% of venture capital dollars in 2018. Even if we leave out the five top-earning metros, there would still be a 37% gap in funding between rural and nonrural counties. In the same year, rural areas received just $120 of venture capital per capita, while nonrural areas received $568 per capita (SEC Form D, Population and Housing Unit Estimates).

This has translated to less investment outside of a small handful of innovation hubs, severely limiting a key resource required to create new economic opportunities in rural America.

These tides are already starting to turn. Recent data suggests that access to venture capital is expanding in rural areas. In 2018, U.S. companies received $153 billion in venture capital funding, but by 2022 this number had increased to $233.2 billion — a 52% increase. During that same time, rural companies increased their venture capital funding by 338%, from $891 million to $3.9 billion, an increase that more than doubled their share of venture capital funding, from 0.6% of total funding in 2018 to 1.7% in 2022 (SEC Form D).

Some investors have already begun to see rural areas as an emerging market with untapped potential in many innovative rural startups. Rural communities offer a diverse array of experiences and viewpoints that can be critical in driving advances in innovation.

This diversity can lead to more creative problem-solving and novel ideas, enhancing the quality of work and output across various industries including tech.

Sho Rust returned to his hometown of Cape Girardeau, Missouri, to launch an artificial intelligence-enabled software company, Sho.ai, in a place that required far less overhead to do business than where he had been in southern California. The local talent pool and broadband infrastructure has allowed him to scale and attract investors in the town his family calls home — not Boston or San Francisco.

Sho Rust

These pioneering rural tech startups lead to innovations that boost local economies and productivity, they can also lead to very real financial returns for investors. As an example, the CORI Innovation Fund’s investment in Disa Technologies, founded in rural Casper, Wyoming, returned four times the investment in just under two years, 103% the Internal Rate of Return (IRR) when Fund I as a whole has a 16% IRR.

Why now is the time to go further

Rural communities are increasingly becoming a pivotal part of the knowledge economy. Federal policies have played a significant role in closing the digital divide by investing in broadband infrastructure. Yet, rural economic development requires additional investments in tech training programs, and support for local tech startups to help rural areas grow their knowledge economies.

In this piece, we’ve focused on broadband infrastructure, tech workforce training programs, and venture capital as essential inputs to grow and maintain a knowledge economy. Other knowledge economy assets include innovation hubs and coworking spaces. These spaces offer high-speed internet, entrepreneurial resources, tech training, and flexible offices, revitalizing rural downtowns which could greatly improve internet access in rural areas.

You can find out more about the Center on Rural Innovation’s work growing rural tech economies here.

Go deeper

Catch up on previous stories in the Rural Aperture Project, and sign up for our newsletter to ensure you don’t miss future stories and research about rural America.

The Rural Aperture Project

-

Story 1Defining rural America: The consequences of how we count

-

Story 2 — Part IWho lives in rural America? How data shapes (and misshapes) conceptions of diversity in rural America

-

Story 2 — Part IIWho lives in rural America? The geography of rural race and ethnicity

-

Story 3The equity of economic opportunity

-

Blog: The overlooked equity conversationRural America in the tech age

-

Blog: Unlocking rural prosperity

The role of tech jobs in equitable development