More Than Numbers: The Threat to Rural Economies When Good Data Disappears

Losing reliable county-level data leaves rural communities without the insights they need to grow, compete, and plan for the future. Protecting this data is essential to ensuring an equitable, informed path forward.

When good public data disappears, rural communities don’t just lose numbers—they lose their roadmap.

For years, chronic underfunding of federal statistical agencies has put reliable, publicly available data at risk. For rural leaders, entrepreneurs, and residents trying to build a more prosperous future, this loss is like navigating a complex economic landscape without a map. And while many look to artificial intelligence as a futuristic guide, this technology is only as good as the information it’s built on. Because large language models are trained on written text, not raw economic data, they can summarize discussions about the economy but cannot uncover the causal reasons for economic trends. At CORI, we rely on this public data to identify the crucial trends in employment and entrepreneurship that guide our program strategies and interventions. Its disappearance is not a niche problem; it is a threat to the future of rural America.

The Problem: Our Economic Scorekeepers are Underfunded

Key federal agencies like the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) and the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) are the scorekeepers of our economy, producing the reliable, publicly available data that organizations such as CORI and countless private businesses depend on to shape strategy. After years of chronic underfunding, these agencies are being forced to scale back. The BEA has already eliminated its detailed county-level tables on self-employment, an important indicator of local entrepreneurial capacity. Former BLS Commissioner, Dr. Erica Groshen, notes that the bureau has lost roughly 20% of its purchasing power over the past two decades, and the outlook is grim: the proposed 2026 federal budget includes staffing cuts of 8 percent at BLS and an alarming 17 percent at BEA, reductions that will almost certainly accelerate the erosion of critical data series.

The Census Bureau, too, has seen cuts. In early 2025, more than 1,000 employees left through buyouts or early retirement (Rampell, 2025). Charged with conducting over 130 surveys each year, the agency is now warning that “if the Bureau does not recruit and retain enough quality employees for [survey] positions, it will not have sufficient and capable staff to complete interviews and collect social and economic data” (FEDweek, 2025). At the same time, the administration disbanded two advisory committees—the BEA Analysis Advisory Committee and the Federal Economic Statistics Advisory Committee—that provided expert feedback on methodology and quality (Reuters, 2025). Combined with the attrition of senior staff, the loss of this oversight raises troubling questions about the reliability of future federal economic statistics (Wang, 2025).

Budget constraints have also blocked efforts to modernize. Instead of incorporating digital transaction data into its price surveys, for example, the BLS still relies on staff physically visiting stores to collect information. As Groshen has observed, limited resources are now “just going to keep the lights on,” leaving no room for efficiency gains that would improve accuracy and ease burdens on businesses. This lack of modernization compounds a long-standing challenge: falling response rates. In the Current Population Survey—the nation’s primary source for unemployment and labor force statistics—response rates have dropped from 90 percent in 2013 to just 71 percent in 2023. Lower participation inevitably weakens the quality of the data, but without investments in new collection methods, the downward trend will continue.

Modernization would not only shore up accuracy; it could also make data more accessible. Today, many federal datasets require some level of data science training to translate numbers into insight, putting rural towns with limited staff capacity at a disadvantage. That is why CORI, in partnership with IEDC through the Economic Recovery Corps program, created an Economic Development Tool that takes publicly available data from the BEA and other sources and makes it more user-friendly—presenting trends over time, offering rural comparisons, and placing the numbers in context. Without reliable federal inputs, however, even these tools lose their foundation.

Why Data Loss Hits Rural Communities the Hardest

This isn’t just about numbers; it’s about equity. Metropolitan areas benefit from a wealth of data sources, both public and private. Rural communities, by contrast, rely heavily on detailed county-level statistics—the very series most at risk of being discontinued. Because rurality itself is often defined at the county level, the loss of granular data strikes at the heart of how we measure and understand rural economies.

Dr. Groshen warns that one of the risks of BLS staff reduction is its unevenness, leaving units responsible for geographic detail, such as county-level annual reporting, especially vulnerable. That hollowing out threatens the geographic granularity that rural stakeholders, businesses, and researchers depend on. The challenge is compounded by the realities of survey research. Reductions in sample size for surveys like the American Community Survey (ACS) disproportionately affect rural America, where small towns and villages already struggle to be represented accurately. Lower response rates in rural areas shrink sample sizes even further, increasing the risk of inaccurate population counts and leaving the needs of these communities underrepresented in official data.

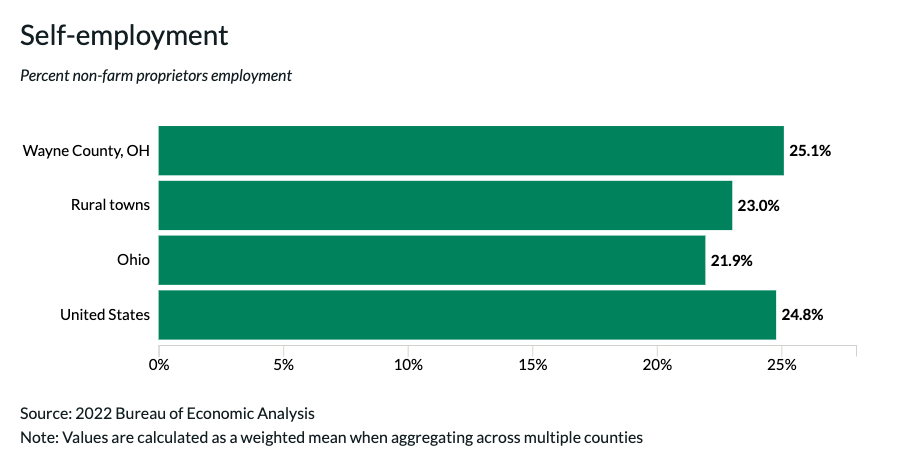

Rural America is far from a monolith. Effective economic development strategies require understanding the unique conditions of each community. County-level data once revealed that Wayne County, Ohio, had a self-employment rate higher than both the state and the nation. That insight could guide local leaders to build on existing entrepreneurial momentum by expanding startup support or developing targeted resources to foster new businesses. Without such data, those opportunities may remain hidden.

Similarly, county-level employment by industry (from the discontinued CAEMP25 series) has long been the backbone of understanding structural shifts in rural economies, such as the decline of manufacturing or the rise of tradable services. Communities use these data not only to track change but also to support grant applications and evaluate programs that depend on industry-specific information.

The elimination of these county-level series—especially those measuring self-employment, sole proprietors, small businesses, and industry mix—undermines the ability to estimate entrepreneurial capacity and track economic diversification year after year. For rural communities, where small businesses and sole proprietorships are often the engines of innovation and resilience, the loss of this detail weakens their ability to make evidence-based arguments for investment, design policies that fit local conditions, and compete on a level playing field with metropolitan areas. Without it, the rural data gap deepens, leaving local leaders to navigate the future with less information and greater uncertainty.

The AI Illusion: Why Technology Can’t Replace Data

It is tempting to think artificial intelligence could fill the growing data gap, but this misunderstands how the technology works. Large language models (LLMs) are powerful tools for analyzing and summarizing existing information. They are trained on vast datasets of text and code, and they excel at identifying patterns and generating human-like text. But they are not a substitute for data collection. At best, they reproduce prevailing narratives—which, in the case of rural America, are often outdated or biased—rather than reveal hidden strengths or emerging trends.

That is why public data remains indispensable. Granular county-level statistics allow researchers to cut through stereotypes and show what is actually happening in rural economies, whether it’s unexpectedly high rates of entrepreneurship or evidence of demographic change. CORI’s Rural Aperture Project demonstrates this power: by analyzing census and ACS data, it has shown that nearly 14 million rural residents identify as Black, Hispanic or Latino, Native, Asian, or multiracial—more people than live in many major U.S. cities—with some demographic groups such as Hispanic and Latino growing in rural areas. These are realities that AI alone may not surface.

LLMs can spot correlations, but patterns alone do not explain why change is happening. Correlation is not causation, and without high-quality data and rigorous research, we cannot identify the true drivers of the widening gap between rural and nonrural America—or design the policies and investments needed to close it.

The Real-World Consequences

When accessible economic data disappears, rural communities are left to plan in the dark. Basic questions become difficult to answer: Is a development strategy working? Are entrepreneurs getting the support they need?

Without trusted public data, strategy gives way to guesswork. Researchers must stitch together less comparable sources, and in many cases, important lines of inquiry vanish entirely. This widens the information divide between well-resourced metro areas and rural communities struggling to make informed decisions.

For rural entrepreneurs and small businesses, county-level data is not abstract—it can be a practical tool for identifying market opportunities, spotting gaps, and understanding regional customer bases. These insights strengthen business plans, help secure loans or investments, and guide choices around hiring, marketing, and expansion. Private data products cannot fully backfill this gap, since many are calibrated on federal data; as public data erodes, so too does the accuracy and reliability of these alternatives. The loss of this data matters more for rural small businesses than large corporations, which can rely on their own transaction-level data. When publicly available data disappears, small businesses are left at a disadvantage, widening the competitive gap between rural entrepreneurs and larger, better-resourced firms.

The loss also constrains other federal agencies. Headwaters Economics is an independent, non-profit research group that curates government data and produces reports and data tools that are widely used by federal agencies such as the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Forest Service, and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. As Headwaters’ Executive Director Patty Hernandez warned, loss of data on employment by industry will hinder these agencies’ understanding of local economies, obscuring how land management policy choices ripple through rural counties—especially in the West, where public lands anchor local livelihoods. Decisions that should be data-driven risk becoming blind guesses.

A Path Forward

This data crisis is not irreversible, but addressing it requires a proactive approach.

-

Fund the basics.Protect and strengthen core series at BEA, BLS, and Census—especially those that offer county-level, annual detail.

-

Safeguard granularity.Prioritize the geographic detail rural analysis depends on; when trade-offs are required, avoid cutting county-level series.

-

Modernize collection.Support efforts that responsibly integrate new data sources and reduce respondent burden so rural coverage improves.

-

Build user-friendly access.Make it easier for local officials, entrepreneurs, and civic groups to find and use the data without a data science team.

Get Involved

We all can play a role in bringing about the changes above, but it will require action. Below are some actions we all can take.

-

ParticipateParticipate in federal surveys of households and businesses. We can all demonstrate that this data is important to us by participating in its collection.

-

Join And SupportJoin The Friends of BLS and The Census Project. Help support these agencies by joining and supporting these independent advocacy efforts.

-

Urge Elected OfficialsUrge your elected representatives, especially senators and members of Congress, to support funding to modernize and disseminate federal statistics. Let your representatives know that strengthening federal data is an important issue that you care about.

-

Encourage LobbyingAsk businesses and business associations to lobby in support of funding for modernization of federal statistics. Businesses should let the federal government know that good economic data is important to them.

Rural places weren’t targeted by data cuts—but they will bear outsized costs when detailed, comparable, public data goes away. If we want smarter investments, stronger small-business ecosystems, and resilient local economies, we have to protect the public data that helps make all of that possible.