The power of “lighter, quicker, cheaper” placemaking in rural America

What does lighter, quicker, cheaper placemaking look like in action? We highlight examples from each of the communities CORI has worked with.

Think about somewhere near your home that you enjoy visiting — it could be a neighborhood walking path, a coffee shop, a park, a library.

Now ask yourself: What are the attributes that make it a place where you want to spend time?

If you find yourself reflecting on how that place is inviting and easy to use, the chances are pretty good that some degree of “placemaking” informed how it came to be that way. Or, as the Center on Rural Innovation’s placemaking expert, Lisa Glover, likes to describe it, “people-powered public space design.”

“It’s all about making sure that the people most local to a place have some kind of meaningful say in the design or the amenities that happen there, especially when we’re talking about public spaces,” Glover said.

Glover’s work with CORI, funded by a Rural Placemaking Innovation Challenge grant from the USDA, has focused on “lighter, quicker, cheaper” — or LQC — placemaking, a version of the process that is relatively low-cost and uses insights from small-scale projects to inform decisions on larger-scale efforts.

How “lighter, quicker, cheaper” placemaking works

Also known as “quick-build” placemaking, LQC provides the ability to try out a concept to get buy-in from people and see if a project is even viable.

“You’d ask yourself, ‘How can I test this idea in the lightest, quickest, cheapest way possible?’” Glover said. “Most of the projects I’m putting on are in the $5-500 range, but it really depends on just what a community is trying to accomplish.”

Glover’s work with CORI has involved piloting placemaking efforts in three rural communities — Pine Bluff, Arkansas; Rutland, Vermont; and Selma, Alabama — keen on developing downtown innovation districts that can attract and retain tech workers and entrepreneurs.

“A lot of innovation happens when we connect with others,” Glover said. “Throughout history, innovation happened in a lot of places when different cultures and different people came together — and the same thing happens in cities and towns today. Studies have shown that you see higher rates of entrepreneurship in places that have a cafe like a Starbucks than in similar places that don’t have the same type of place where diverse connections happen.”

What does lighter, quicker, cheaper placemaking look like in action? Here are examples from each of the communities CORI has worked with:

A spruced-up landscape

To complement Pine Bluff’s ongoing efforts to revitalize the downtown streetscape, the community’s project focused on a neglected former bank lot located among several recently renovated buildings.

“A group of stakeholders felt like that was a space that really needed to be cleaned up to make this whole area feel like a cohesive place that people want to be in,” Glover said.

Together, they’ve developed plans to add new plants to the landscape and invested in powerwashing what was already there, which breathed new life into benches. There are also plans to install a little free library to the lot.

“It can be helpful to create reasons for people to go somewhere and activities for them to do to enliven a space,” Glover said.

An unlikely art gallery

In Rutland, which has embraced several lighter, quicker, cheaper ideas, the owner of a long-neglected downtown lot allowed private citizens to clean up the space and transform it into an open-air public art gallery.

“The owners didn’t have to do that, but the fact is that they did and it’s turned an area that a lot of people avoided in Rutland into a place that has a nice reason for them to stop by and see what’s going on,” Glover said.

Local government also acted on concerns about pedestrian safety near the city’s new innovation hub and partnered with the community to create a new mid-block crosswalk. The city contributed road paint and planters while citizens added flowers to beautify the addition. The immediate popularity of that project led to it being renewed for another season.

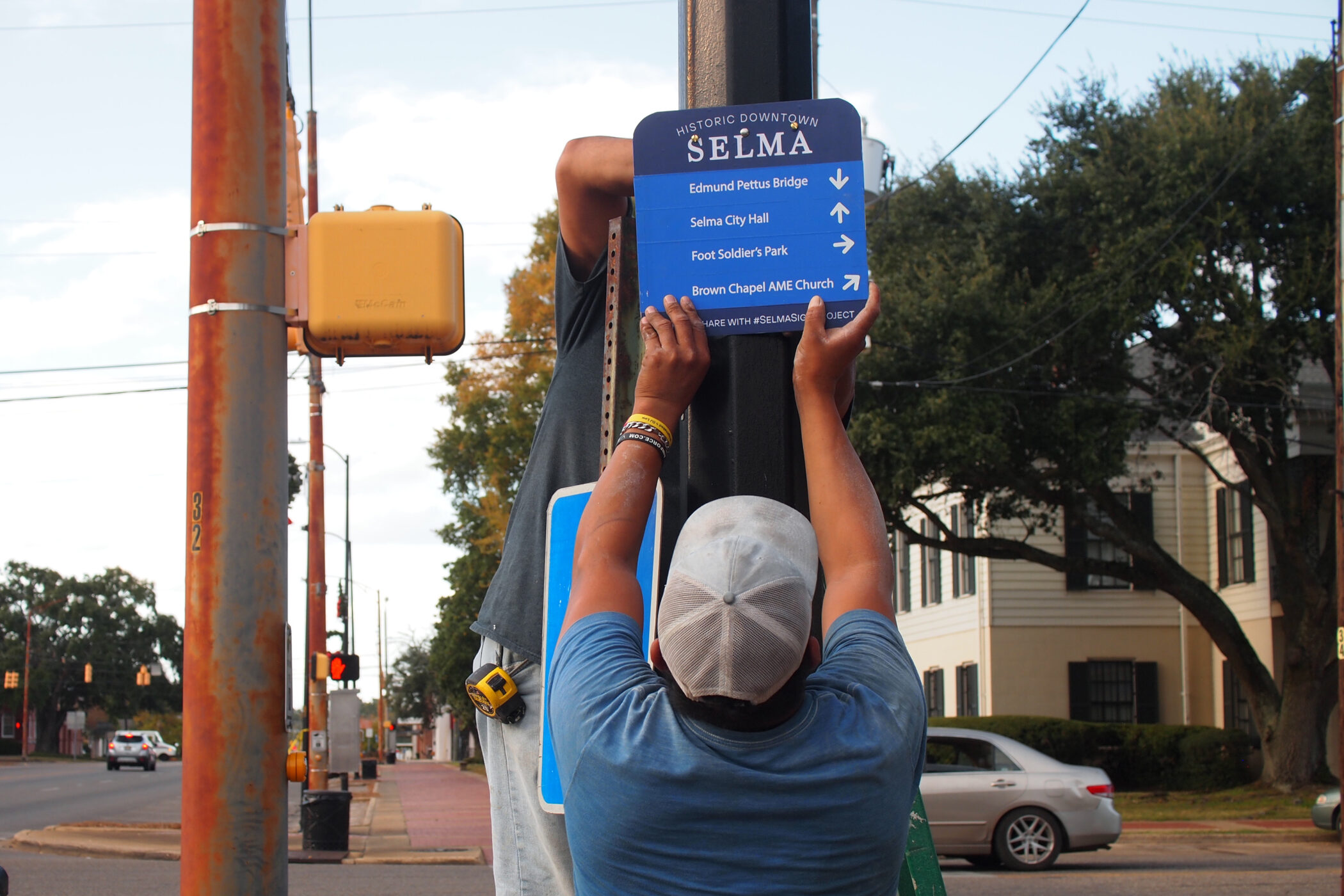

Long-awaited signage

A key location in the U.S. civil rights movement, Selma’s historic downtown had long been without wayfinding signs that could direct visitors to places of note.

In the course of her work, Glover convened community members to provide feedback on designs that were part of an existing plan and brainstorm future efforts. And that set the community on its way. A group applied vinyl stickers to aluminum signs and posted them around downtown, the first tangible progress for an idea that had been in the works for 20-plus years.

“It got people excited about wayfinding again,” Glovers said. “Giving people something actionable to do gave them a reason to show up to what otherwise might have felt like just another chance to talk about something. … It’s a step in the right direction.”

What you can do to get started

For places concerned about population loss, or improving community engagement, placemaking can be a useful, low-cost way to make sure people want to stay because they feel like they have a real stake in their community.

If you think your community could benefit from a lighter, quicker, cheaper placemaking work to complement an emerging innovation hub, get in touch with our team to learn more. And be sure to subscribe to CORI’s newsletter to hear about the exciting things happening in rural innovation across the U.S.