Case study: Michigan Tech’s Global Entrepreneur in Residence Program creates jobs and attracts investment

Discover how Michigan’s Upper Peninsula is turning brain drain into brain gain by leveraging the Global EIR program to attract international talent and fuel rural innovation.

While many rural communities struggle with brain drain — when talented graduates pursue opportunities in major cities, taking their skills and potential with them — Houghton County in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula (U.P.) has flipped the script, proving rural America can be a magnet for global talent.

Michigan Technological University has tapped into an underutilized program to catalyze local economic development. The Global Entrepreneur-in-Residence (Global EIR) program is a nonprofit initiative that offers a pathway for universities to employ highly skilled immigrant entrepreneurs while they start businesses in the U.S. using cap-exempt H-1B visas.

In Michigan alone, the Global EIR program has attracted international founders who have collectively raised nearly $30 million in venture capital and created 174 jobs as of 2024. These startups tackle diverse regional challenges, from monitoring drinking water for contaminants to mitigating supply chain risks to addressing food insecurity and creating diagnostic tests for livestock.

The Global EIR program is rare in rural communities, where institutions may already be doing similar work without realizing it has an official framework and national support network. Through a partnership with Global Detroit and funding from the State of Michigan, Michigan Tech offers a compelling example of how to leverage the Global EIR program as a transformative economic development opportunity.

The Global EIR Program bridges talent gaps

The Global EIR program addresses a critical bottleneck in the American immigration system. While the standard H-1B visa program is capped at 85,000 annual approvals granted through a nationwide lottery with a ~25 percent chance of selection, universities and affiliated nonprofits can sponsor immigrants through cap-exempt H-1B visas, which have no numerical limits.

This creates an opportunity for rural institutions struggling to attract talent. International entrepreneurs can work part-time for universities — typically 8-20 hours per week — while building their companies and obtaining longer-term legal status (e.g., a green card) to remain in the United States. The arrangement provides entrepreneurs with income, health benefits, and mentorship roles while giving universities access to diverse talent and entrepreneurial expertise.

“This pathway is tried and true. It’s not complicated,” says Steve Tobocman, Executive Director of Global Detroit, the organization that helped raise awareness of and expand the modern Global EIR model. “Healthcare does this all the time.”

Michigan Tech’s approach to a national model

Michigan Tech had been operating what amounted to a Global EIR program for years before learning it had an official name. The university regularly used cap-exempt H-1B visas to retain international graduate students for startup projects, hiring them to advance faculty research while they built companies based on university technologies.

“We used the Global EIR model before we knew it was a thing,” explains Dr. Jim Baker, Senior Associate Vice President for Research and Innovation at Michigan Tech. The approach typically involved faculty research that included international graduate students, helping them become part of founder teams, hiring them under cap-exempt H-1B visas, securing Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) grants, and subcontracting work back to the university.

When Michigan Tech connected with Global Detroit more than five years ago and learned about the formal Global EIR framework, they gained access to best practices, increased throughput, and became part of a national network spanning seven Michigan universities.

Immigrant entrepreneurs add value to their host universities

Michigan Tech operates Global EIR placements through three distinct models, allowing flexibility based on founder backgrounds and university needs:

- Research advancement: Entrepreneurs work directly in university labs with faculty members, advancing technology while building companies. This represents the standard model, where founders serve as research scientists or engineers while developing startups.

- Commercialization support: Founders work within the university’s commercialization office, leveraging their expertise to assess incoming technologies and support knowledge transfer initiatives. Their entrepreneurial perspective helps evaluate whether innovations have market potential.

- Campus-wide expertise: Founders with specialized skills — such as data science — support other university functions. One Global EIR developed AI software to review thesis formatting requirements, then expanded the tool’s scope for federal contracting applications.

“We talk across campus about where the ‘free person’ with a skillset can fit with needs and add value to the university,” Baker notes.

The entrepreneurs can also give guest lectures, offer internships, and serve as mentors advising other founders and conducting market research for local startups.

Measuring economic impact in rural settings

With bipartisan support, the state allocated $10 million to the Michigan Global Talent Initiative across the 2022-23 and 2023-24 budgets, dedicating approximately $1.75 million to statewide Global EIR program expansion.

The program’s success metrics demonstrate substantial return on investment for rural communities. The Global EIR program expanded statewide to seven university partners, placing 23 fellows from six companies, with founders raising close to $30 million in capital and creating 174 jobs. Between 2020 and 2024, the amount of private investment raised in Houghton County and throughout the state outperformed the average raised in rural counties across the country, reflecting investor confidence and interest in local startups:

For Michigan Tech specifically, the impact extends beyond direct job creation and startup investment. The program challenges the cultural norm where graduates typically pursue traditional employment with an existing company rather than entrepreneurship. “By having a Global EIR program and celebrating that they get to be in control of their own destiny and do what they are passionate about, we are normalizing that outcome,” explains Baker.

The economic development benefits compound in rural settings where talent density is naturally lower. In Houghton County’s small population, each new founder creates critical mass for peer networks and enables ecosystem development that wouldn’t otherwise exist locally.

“Every additional founder is a win,” says Baker. In a county with approximately 37,500 residents, “Adding one founder means moving the needle.”

Overcoming rural network limitations through strategic connections

The Global EIR program faces distinct challenges in rural areas, particularly around network access. Baker acknowledges this issue in the U.P.’s entrepreneur community: “They just don’t have the humans. They have incomplete and loosely connected networks because there are just not enough people.”

Michigan Tech addresses this through deliberate engagement strategies, emphasizing the importance of relationship-building and events to foster collaboration. The university connects founders with Global Detroit’s statewide network, facilitates relationships with regional economic development organizations, and enables access to external networks that rural companies need for success.

“In order for a company to be successful, they will have to access talent and capital outside of the area,” Baker explains. While some local economic developers worry about “losing” entrepreneurs to other regions, Baker focuses on enabling company success wherever it leads. His philosophy: entrepreneurs who succeed elsewhere often return to invest in their communities after achieving financial success.

Implementation roadmap for rural universities

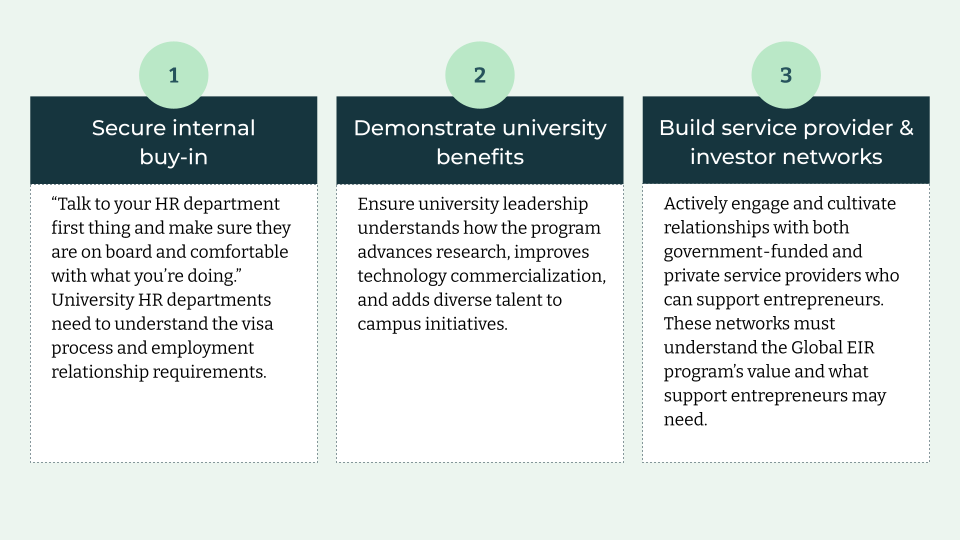

Baker’s advice for rural institutions considering a Global EIR program emphasizes three critical steps:

At Michigan Tech, the Global EIR program application process focuses on entrepreneurial sincerity rather than just visa seeking. They evaluate whether applicants have legitimate business plans, team-building capabilities, and plausible paths to market success.

National network effects and scaling potential

Global Detroit’s role extends beyond Michigan through a Global EIR National Peer Network supported initially by Kauffman Foundation funding. The organization provides implementation support to communities interested in launching a program, including sample applications, employment agreements, and strategic guidance on funding and university partnerships.

“Our theory of change is that we’re trying to get this adopted as best practice for any startup ecosystem,” Tobocman explains. Five additional states besides Michigan — California, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Washington — have created state appropriations to support Global EIR.

The network operates with what Tobocman describes as “a very collaborative, ‘we’re in this together’ ethos,” where participants share resources and learn from each other’s experiences rather than competing for founders.

Economic development strategy for rural innovation

The Global EIR model offers rural communities a practical approach to economic diversification that doesn’t require major infrastructure investment or policy changes. Universities already possess the institutional capacity to sponsor visas and employ entrepreneurs, while international talent brings diverse perspectives and skills that complement existing regional strengths.

“I’m continually impressed with how impactful immigrants have been to the innovation economy,” Tobocman reflects. “Startup visas are not a Silicon Valley issue, they’re an American issue, a job-creation issue.”

For rural institutions operating similar informal programs, formalizing them as Global EIR initiatives provides access to best practices, national networks, and proven frameworks. The approach creates competitive advantages for startup ecosystems while building cultural diversity in entrepreneurial leadership.

Baker emphasizes this core value: “A diverse team is a complete team.”

Building tomorrow’s rural innovation economy

Michigan Tech’s experience demonstrates that rural communities don’t need to accept talent drain as inevitable. By leveraging existing university infrastructure and federal visa pathways, rural institutions can attract entrepreneurial talent that creates jobs, raises capital, and normalizes innovation as a career path.

The program’s success in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula — from informal experimentation to formal statewide expansion — provides a replicable model for rural universities nationwide. With proven economic returns and growing state-level policy support, the Global EIR program represents a tested strategy for rural economic development.

For communities ready to transform brain drain into economic gain, the pathway exists. The question is whether rural America will seize this opportunity to build more diverse, innovative, and economically resilient communities.

Additional resources

For more information, please contact Global Detroit at info@globaldetroitmi.org, and see ShawneeXP Game Accelerator’s August 21, 2025, presentation, “Virtual Community Connections: Global Entrepreneurship in Residence, Portsmouth, OH.”