Continuation of the Affordable Connectivity Program can avoid cascading economic challenges for low-income families and underserved neighborhoods

Policymakers talk about the importance of broadband like it’s a utility — on par with life necessities like clean water, nutritious food, adequate shelter, and electricity. But since the Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP), which fully subsidized or significantly reduced the cost of internet for 23 million households, ended in 2024, and legislation to expand the program has stalled, the gap between acknowledging broadband’s essential nature and ensuring its affordability and accessibility for all has widened.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) launched the ACP in January 2022 to bridge the digital divide by offering monthly subsidies to help low-income residents afford either fixed (home) or mobile internet connectivity. By January 2024, the ACP served about 21.7 million subscribers nationwide, including 3.1 million subscribers in rural counties and 2.6 million in persistent poverty counties. The White House has called on Congress to provide additional funding for enrolled participants and bills have also been introduced in the Senate and House to continue the program.

For most participants, the ACP was the difference between having access to the opportunities that connectivity offers and being left behind. Over two-thirds of participants had inconsistent or nonexistent connectivity before joining the ACP, largely because they could not afford the monthly bill. Importantly, subsidized internet access had a multiplier effect for users of the program: according to the Benton Institute for Broadband & Society, every dollar spent on ACP service subsidies resulted in nearly two dollars in benefits to subscribers.

ACP’s interrupted progress leaves vulnerable, marginalized households facing tough choices

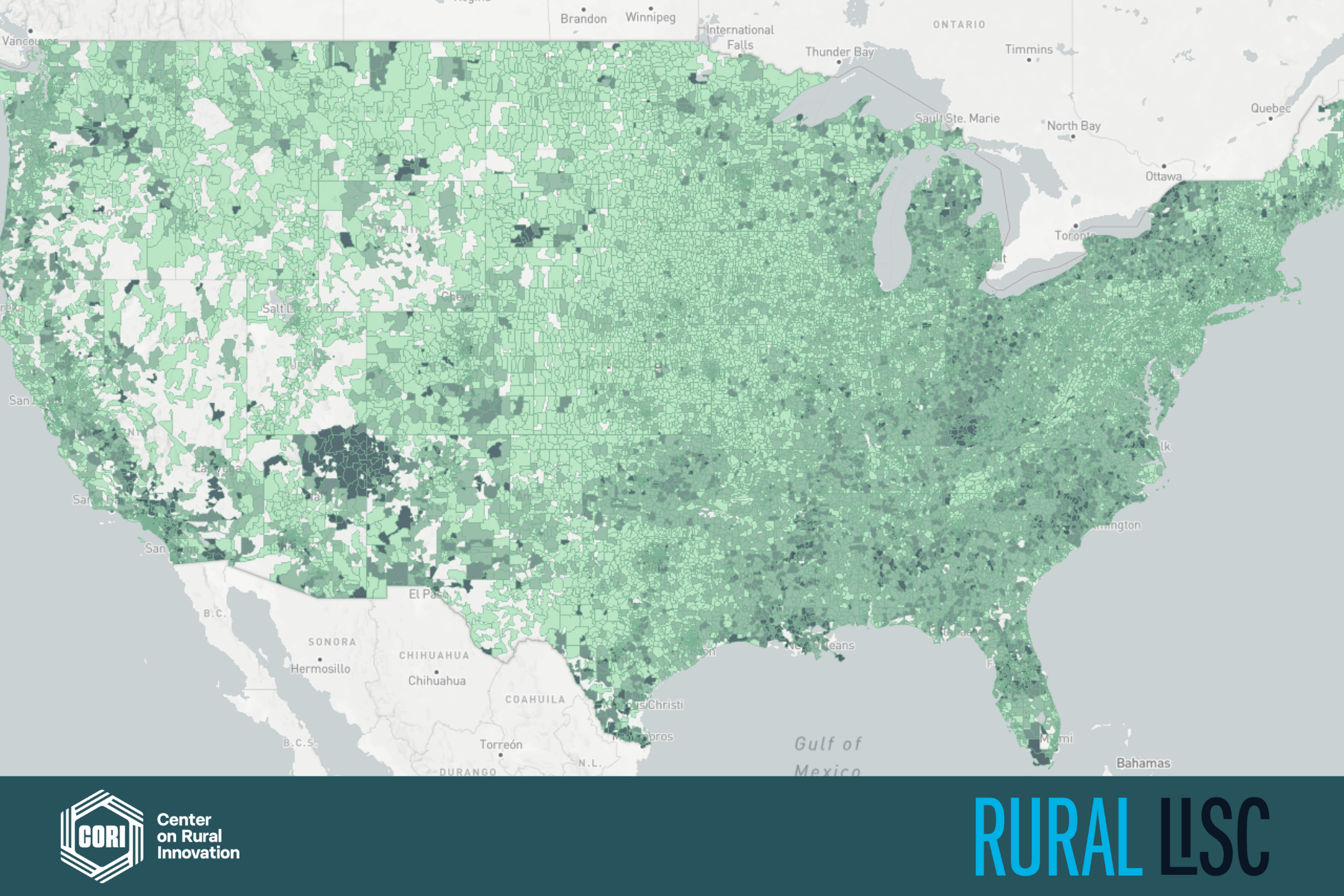

To visualize the ACP’s impact and analyze the repercussions of the program ending the Center on Rural Innovation, in partnership with Rural LISC, created a map of program utilization across time and geography.

The map reveals that average monthly national participation rates among eligible households steadily increased over the program’s nearly 2.5-year lifespan, from 25.3% in 2022 to 45.1% in 2024. In persistent poverty counties, the impact was even more pronounced, with average monthly participation rates climbing from 31.9% in 2022 to 54.2% in 2024, representing $87.7 million in average monthly claimed subsidies in 2024.

Toggle the slider button to see how ACP enrollment increased by Zip Code as a share of eligible households in the Zip Code over the lifetime of the program.

Without these crucial subsidies, low-income households face difficult choices. They must either maintain their internet service package and pay full price, switch to a cheaper, potentially inadequate service tier with slower speeds (if such service is available), or cancel their internet subscription entirely.

Failing to refund the ACP has far-reaching consequences for low-income residents and other vulnerable populations, extending well beyond the immediate loss of internet access, slower connectivity, and more expensive monthly bills.

Repercussion 1: ACP households will have significantly reduced economic opportunities

A good broadband connection provides access to online tools that can save people substantial amounts of money, including virtual services such as telemedicine. According to an evaluation of telehealth visits among patients with cancer conducted in 2021, “The estimated mean total cost savings ranged from $147.4 to $186.1 per visit.”

More broadly, when households lose internet access, they also lose access to pathways to upward mobility via education, training, and higher-wage job opportunities. The loss of potential future earnings for families and individuals who cannot access proven educational and work pathways will be widespread as ACP termination forces families to disconnect.

Repercussion 2: Low-income residents will have reduced access to public safety and government services

Many ACP subscribers used their subsidy for mobile connectivity, which provides critical access to public safety and human services, such as:

- Emergency alerts and storm warnings

- 911 services — especially for households without landline access or in situations requiring discreet communication (e.g., domestic violence situations)

- Roadside assistance in rural areas with sparse populations and low traffic

- Connection to human services or government services, including the ability to be contacted reliably by a child’s teacher or reminders of doctors’ appointments

Now that ACP funding has expired, former subscribers may cancel their service or use it only occasionally, reducing or eliminating their connection to these vital services.

Repercussion 3: Fewer dollars will circulate in local economies

The expiration of ACP subsidies forces households to reallocate their budgets, diverting funds that would otherwise circulate directly and indirectly in local economies.

By January 2024, approximately 21.7 million households were enrolled. Assuming each household received a $30 monthly subsidy, this represents $651 million per month or $7.8 billion annually that is no longer available for local spending. Collectively, this is a significant amount of money no longer flowing into the economy directly or freeing up other resources for families to spend on non-internet essentials.

Repercussion 4: BEAD Program effectiveness will be compromised — particularly in rural areas

The ACP increased the total number of internet subscribers and provided reliable payments from households that often would not otherwise have internet access. Following the program’s discontinuation, internet service providers (ISPs) applying for funding through the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program will have a harder time serving the most remote and economically disadvantaged areas, where the difference between five subscribers per mile and seven can make or break the viability of a business model. Without the increased penetration and revenue provided by the ACP, some ISPs will need to request more BEAD funding than previously anticipated, and others will simply not apply to difficult-to-serve areas at all.

Repercussion 5: Restarting the program will be difficult and expensive

Restarting the ACP is not guaranteed and depends on congressional action, but given how internet access is so often framed as a necessity and not a luxury, there is a good chance it will be reinstated. However, when this happens, the process will be much more costly and complex than it would have been to continue the existing program for several reasons:

- Staff who left will need to be rehired or replaced

- Trust will need to be rebuilt with eligible households, particularly those for whom service was cut off

- Subscribers will need to complete the onerous enrollment process again

Refunding the ACP would have far-reaching benefits

The Affordable Connectivity Program has proven to be immensely beneficial for low-income subscribers, improving access to public safety, government services, telehealth, economic opportunity, higher education, and more.

In addition to supporting vulnerable populations, the ACP bolsters local economic vitality and contributes to the viability of the BEAD Program.

It’s on the map: The ACP program’s impact is far-reaching. Households all across the country participated in the program – many in neighborhoods that could see future investment in digital equity – such as skills-building programs and greater computer access – as the NTIA makes awards in the Digital Equity National Competitive Program.

As such, there is a strong case for restarting and maintaining the program — despite the expenses and challenges involved. By ensuring affordable, ubiquitous internet access, we not only empower individuals and communities but also invest in the nation’s digital future and economic resilience.

Special thanks

This research wouldn’t have been possible without the generous support of our partners at Rural LISC.